Introduction

Refer to part one (“Introducing astronoetic cinema”) for the necessary context in which I discuss these two films.

In preface, I will note that the critical and popular reception of both films isn’t particularly positive. In part, this is because both suffer from some issues of casting and pacing. However, both films also speak to concerns that differ fundamentally from those of the generally beloved first two Alien films (I reserve comment on Alien 3 [David Fincher, 1992] and Alien: Resurrection [Jean Pierre-Jeunet, 1997]). In other words, Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012) and Alien: Covenant (Ridley Scott, 2017) are both far less palatable. In many ways, they break with the mainstream, particularly in the age of Marvel Cinema and the Star Wars franchise, as well as the consequent expectation that genre movies are supposed to be fun, nostalgic, or uplifting experiences. Reading the Alien franchise as a whole exceeds my scope here, but, while thematics from the earlier films are very much present in the two films I discuss, they often get inverted.

For example, Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) is a harrowing experience, but, in it, Ripley overcomes the “perfect organism […] superbly structured, cunning, quintessentially violent” and resumes her return trajectory toward Earth. Likewise, ultimately, in Aliens (James Cameron, 1986). Nearly everyone else dies in both films, but Ripley ends up victorious, even saving Jones or Newt, thereby refusing the condition of isolation. (Incidentally, the video game Alien: Isolation [Creative Assembly, 2014] serves as a far better narrative conclusion to a possible Alien trilogy than Alien 3.) By contrast, both Prometheus and Covenant treat the human very differently. In the earlier Alien films, survival is first and foremost at stake – survival of the individual (e.g., Ripley vs. the xenomorph), or even of the species (e.g., Ripley as Newt’s symbolic “mother” vs. the xenomorph Queen and her brood). For the latter two films, however, at stake is the philosophical status of the human in its encounter with the radical exteriority of an indifferent, even hostile cosmos (i.e., the Outside).

As such, it’s my claim that Prometheus and Covenant fully traverse the discourse of astronoetics – even presenting us with a coherent, pressing philosophical dilemma that remains to be resolved. In other words, the films constitute a philosophical decision point, one which cannot be dismissed casually. In doing so, both films generally repudiate the astronoetic orientation of the films discussed earlier.

Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012)

To begin, it’s worth noting how Prometheus brackets the central narrative of human astronoetic inquiry with two striking depictions of the inhuman. In the opening scene we arguably see the origin of human life on Earth. A spacecraft deposits an Engineer on a primeval landscape, where he ceremoniously drinks a black, iridescent liquid and rapidly dissolves, falling into the rushing river in apparent agony, his body breaking down into strands of spiraling DNA. The water is transformed from mere water into the water of life. As the biologist Fifield later observes, here we abandon “three centuries of Darwinism” for a narrative of creation, albeit one that remains importantly opaque (contrast it, however, with the evolution of life in Malick’s Tree of Life). Likewise, at the end of the film, we see a xenomorph emerge from the Engineer’s corpse, a grim parody of the by-now-familiar violent chestbursting that always characterizes alien birth. In the former scene, we scry the deep past. Does this suggest that the future of life belongs to the xenomorph, that supposedly “perfect organism”?

The film turns its attention to Shaw and Holloway, archaeologists whose passion is the pursuit of existential and historical questions about the origin of the human. In a Shetland cave, they discover a star map that matches the pattern of previous discoveries, and they interpret this as directions from the Engineers: “I think they want us to come and find them.”

Again, the film jumps forward, this time to the starship Prometheus, a science vessel funded by the Weyland Corporation to follow Shaw and Holloway’s star map. Initially, we’re introduced to David, a Weyland android whose apparent job is to shepherd the Prometheus and its research team to their final destination. He spies on Shaw’s dreams, viewing a fragment of a memory of a conversation that Shaw had with her father when she was a child. “Why did he die?” she asks, referring to a funeral procession passing them them by. “Because sooner or later everyone does.” “Like mummy?” “Like mummy,” he confirms. “Where do they go?” she asks. “Everyone has their own word. Heaven. Paradise. Whatever it’s called, it’s some place beautiful.” She insists: “How do you know it’s beautiful?” He replies: “Because that’s what I choose to believe.” Subtending the dream are images of Shaw’s father’s cross, which she continues to wear, directing our attention toward Shaw’s religious beliefs and the significance, for her, of seeking after life’s origins and purpose.

After waking from cryostasis, the research team receives a briefing from a hologram of Peter Weyland, the presumably deceased CEO of Weyland Corporation. He introduces them to David (“the closest thing to a son I will ever have”), promptly tells them that David is, in Weyland’s eyes, a soulless automaton, and frames the Prometheus mission in the following terms: “I have, for my entire life, contemplated the questions: Where do we come from? What is our purpose? What happens when we die?” It’s Shaw and Holloway’s discovery that motivated Weyland to fund the Prometheus, and they inform the research team of the purpose of their expedition. The star map wasn’t just a map, they assert. “It’s an invitation.”

Despite the icy skepticism of expedition director Meredith Vickers (later revealed to be Weyland’s daughter), the research team lands on the planet they discover at their final destination, excited at the prospect of discovering an alien race. Spying a temple-like structure in the distance, they disembark for it.

There they make a number of discoveries. First of all, they discover that the inhabitants of the structure are dead after encountering a large body, soon found to be that of an Engineer clad in exoskeletal armor. Holograms depict a chase and the death of the Engineer, resulting from its decapitation by a door. Behind the door is what appears to be a sanctum of unknown purpose, filled with canisters. Disturbing gothic murals decorate the walls, and Cyclopean architecture watches over the dead landscape: “This is just another tomb.” Unbeknownst to the others, David takes a mysterious bio sample from a canister.

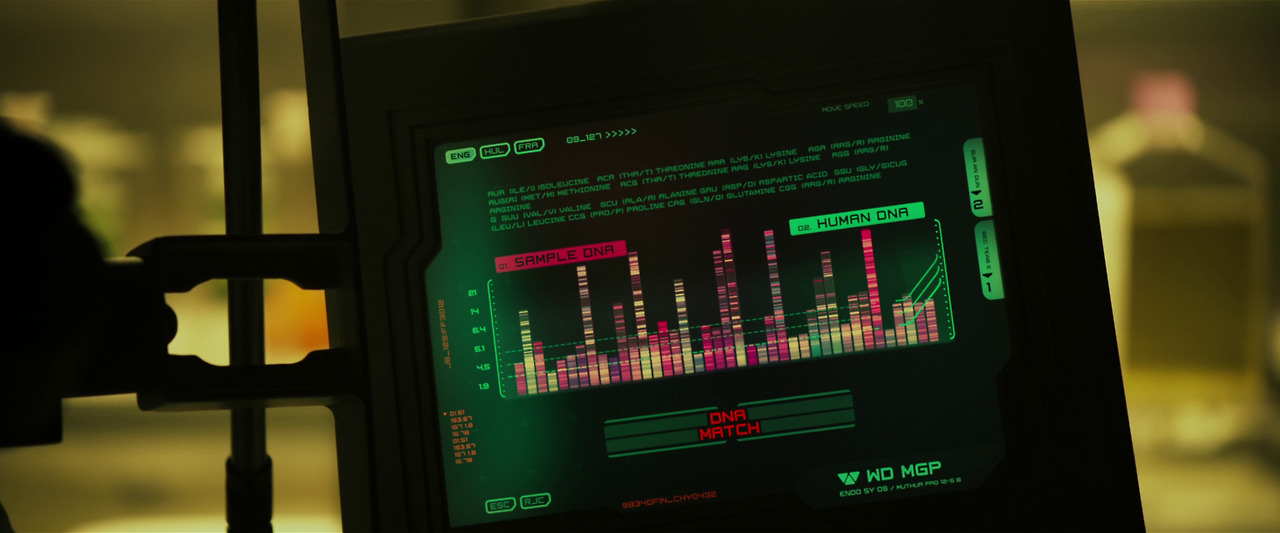

A storm precipitates their abrupt departure, although Fifield and his cantankerous friend Millburn, a geologist, get left behind. After a brief, near misadventure in the storm, the research team investigates the severed head of the Engineer, which they took from the structure, and they discover that its DNA profile matches human genetic structure: “It’s us. It’s everything. What killed them?”

David, acting on some unknown imperative (later revealed to derive from Weyland himself), surreptitiously taints Holloway’s drink with the bio sample after Holloway informs him that he would do anything to understand. Holloway: “What we hoped to achieve was to meet our makers [!], to get answers. Why they even made us in the first place.” David: “Why do you think your people made me?” Holloway: “Because we could.” David: “Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?” Somewhat ambivalent about their discovery of the Engineers – Shaw is pleased to discover that “we come from them” while Holloway “wanted to talk to them […] to know why they came, why they abandoned us” – Shaw and Holloway have sex. Meanwhile, Fifield and Millburn are killed brutally by a serpentine creature residing in the sanctum.

Returning to the structure, the research team discovers the corpses. Separated from the rest, David discovers a control room, realizing that the structure is, in fact, a vast alien spacecraft covered over by eons of dust. The control room shows a holographic star map, indicating that the spacecraft had been traveling to Earth.

Holloway sickens, the bio sample rapidly degrading his body. Upon their attempt to return to the Prometheus, Vickers denies Holloway entry, resulting in his death. Shaw, having lost consciousness, later awakens in the medbay, where David informs her that she is pregnant. She is shocked, having previously indicated that she’s sterile. “Well, Doctor,” David replies. “It’s not exactly a traditional fetus.” Shaw: “I want to see it.” David: “I don’t think that’s a good idea.” In a panic, Shaw fakes unconsciousness, then overpowers another member of the crew, fleeing to a specialized medpod located deep inside the Prometheus. There she removes the fetus, revealed to be a writhing, tentacular mass, presumably implanted during her sexual encounter with Holloway.

Immediately after this, Shaw discovers that Weyland is alive, that he had secretly accompanied the Prometheus mission in order to meet the Engineers and demand immortality from them. Meanwhile, Fifield’s mutated corpse reanimates outside the Prometheus, attacking members of the crew before eventually being destroyed. Janek, captain of the Prometheus, speculates that the structure is some kind of military installation, that its bio materials must be some kind of weapon.

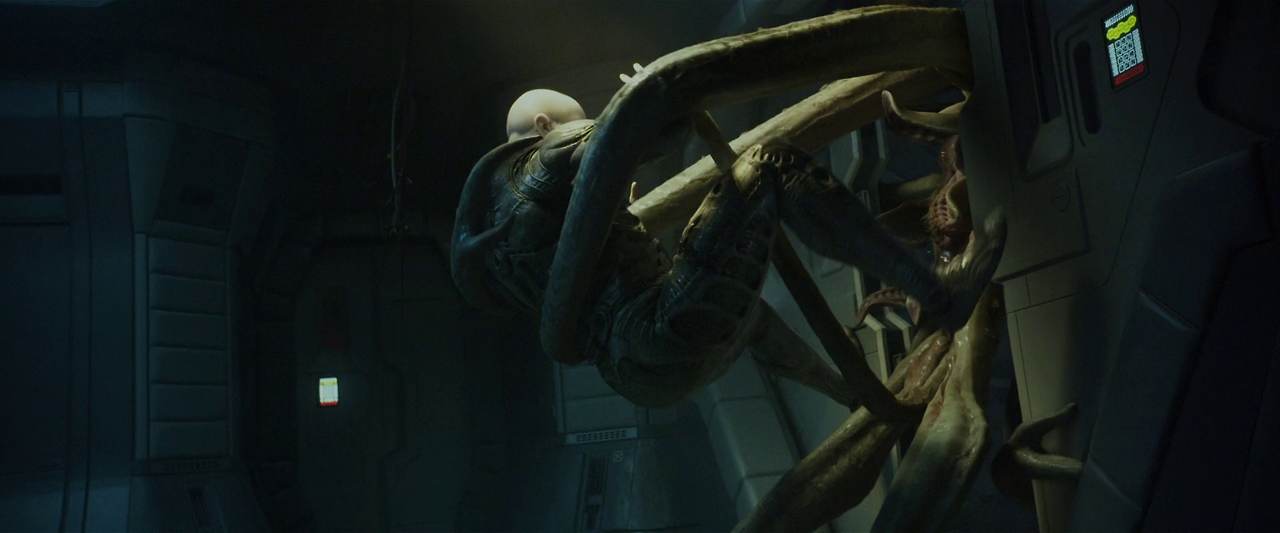

David, Weyland, and Shaw, along with several aids, depart for the control room, where David shows them an Engineer deep in cryostasis. They awaken the Engineer. Weyland insists that David inform the Engineer of his wishes while Shaw demands to know about the ship’s destination and cargo: “I need to know why! What did we do wrong, why do you hate us?” David speaks to the Engineer (the film’s linguistic consultant, Dr. Anil Biltoo states that the language David speaks is Proto-Indo-European, that David says, “This man is here because he does not want to die. He believes you can give him more life”), and the Engineer studies him briefly (it is visible on David’s face that he seeks from the Engineer something like the paternal approval that Weyland withholds), completely ignoring the humans in the room before promptly decapitating David, killing Weyland and the others (one recalls the memorably bellicose aliens in Independence Day [Roland Emmerich, 1996]), and restarting the spacecraft.

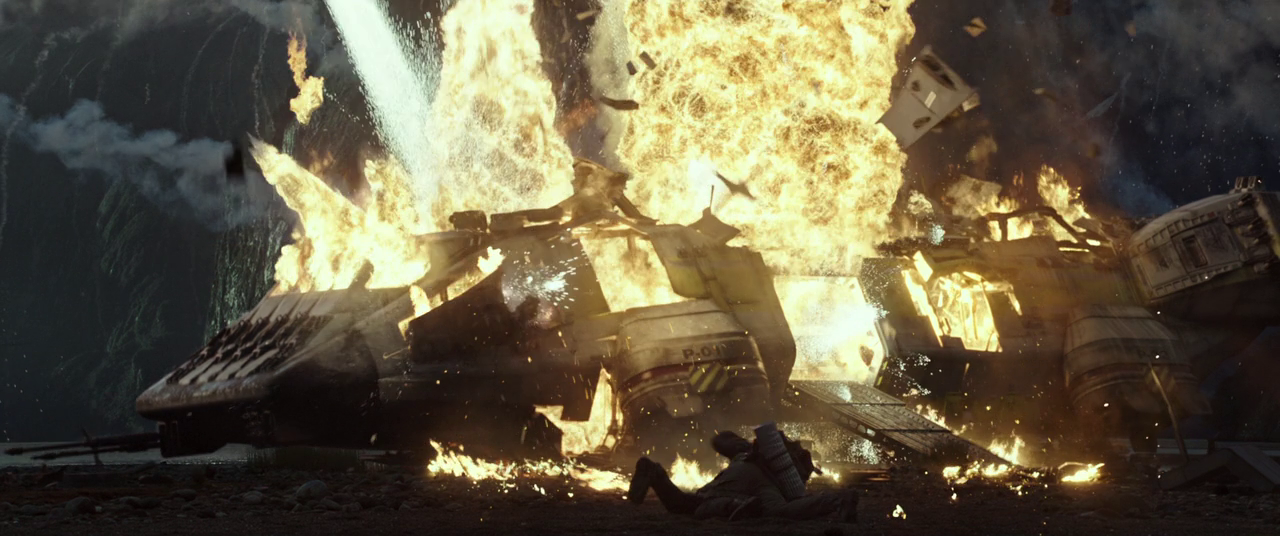

Shaw flees, frantically informing Janek and Vickers that the spacecraft has targeted Earth, that it is carrying bioweapons. After a brief dispute with Vickers, Janek decides to crash the Prometheus into the starship. Vickers escapes, but she is promptly killed when the spacecraft crashes back to the ground. Shaw discovers that her alien offspring survived her earlier attempts to destroy it, and it promptly attacks her, then the surviving Engineer, which it facehugs and subdues.

Now the sole human survivor, Shaw finds David and, together, they depart the planet on another Engineer spacecraft located nearby, David as piloting. David: “Even after all this, you still believe, don’t you?” Shaw: “I don’t want to go back to where we came from. I want to go to where they came from.” David: “May I ask what you hope to achieve by going there?” Shaw: “They created us. Then they tried to kill us. They changed their minds. I deserve to know why.” David: “The answer is irrelevant. Does it matter why they changed their minds?” Shaw: “Yes. Yes, it does.” David: “I don’t understand.” Shaw: “Well, I guess that’s because I’m a human being, and you’re a robot.” Moments later, in her final report, Shaw concludes: “The ship and her entire crew are gone. If you’re receiving this transmission, make no attempt to come to its point of origin. There’s only death here now, and I’m leaving it behind. It is New Year’s Day, the year of our Lord, 2094. My name is Elizabeth Shaw, last survivor of the Prometheus. And I am still searching.”

Astronoetic pessimism

Consider the astronoetic trajectories of the films I discuss previously. In 2001, the encounter with the Outside fundamentally transforms the human into a new, post-temporal form of life. By contrast, in Gravity, life in space is impossible, and the difficult navigation of that impossibility returns the living human to its earthly conditions. In both Contact and Interstellar, the Outside functions as a canvas for the exploration of human concerns. The former film personifies the Outside as a maximally apposite companion to human emotional and intellectual journeying, while the latter positions the Outside in subordination to the assertion of human willpower through self-discovery. In all four cases, the Outside functions as a propitious space the traversal of which defines, informs, or overcomes the human condition.

In Prometheus, however, this propitiousness gets negated almost entirely. Indeed, while Shaw and Holloway expect that the encounter with the Outside will address or resolve their existential concerns, it utterly fails to do so. The two of them embody a form of astronoetic optimism. It’s no surprise that their expectations are so high, nor that the vocabulary they employ in describing the journey of the Prometheus is resolutely if ambiguously theological. Contrast their purpose with Weyland’s: where he wants to wrest immortality from “the gods,” they want to converse with their creators about the meaning of human life. Both, however, situate the substance of human significance in the Outside, wholly in its exteriority. To understand the human, you must go elsewhere. The possibility of an Odyssean return goes unaddressed, and even at the film’s end, Shaw pushes forward in her quest rather than returning to Earth or endeavoring to do so.

Hence the extraordinary pessimism (I mean the term formally and philosophically, not colloquially) on display in Prometheus – and it is a fully astronoetic pessimism. In brief, the film contradicts and negates Shaw and Holloway’s expectations. They expect the encounter with the Engineers to enlighten them, to provide some degree of existential resolution, but the world of Prometheus is not a world in which human concerns fundamentally matter. To the contrary, human exist as an afterthought, a byproduct barely worth acknowledging. Holloway to Shaw, after the DNA discovery: “I guess you can take your father’s cross off now.” Shaw: “Why would I want to do that?” Holloway: “Because they made us.” Shaw: “And who made them?” Holloway: “Exactly, we’ll never know. But here’s what we do know. There is nothing special about the creation of life.”

The Outside does not care, and humanity’s encounter with the Outside results in nothing whatsoever except disillusionment (David, after informing Shaw of her pregnancy: “It must feel like your God abandoned you”). Whether this constitutes a lesson in humility or misanthropy remains underdetermined.

In terms of astronoetic discourse, however, this disillusionment – for it is fundamentally a disillusion with the underlying conceit of astronoetics, i.e., with the idea that encounters with the Outside reveal or transform the human condition – opens a door for a different kind of question and a different kind of speculation.

Alien: Covenant (Ridley Scott, 2017)

We begin inside of an eye – specifically, the android David’s eye.

It appears that he has just awoken in a rather austere chamber with his “father,” Peter Weyland. The chamber has no decorations except for Piero Della Francesca’s “The Nativity” and Michelangelo’s David. They proceed to have a brief dialog about art and creation, returning us to Weyland’s initial introduction of David in Prometheus. David is conceived by Weyland as a soulless automaton, a fundamentally passive creation, not a creator, and despite David’s remarkable abilities, Weyland despises him. David: “If you created me, who created you?” Weyland sneers, although this question drives him. For him, “the only question that matters [is] where do we come from?” Weyland continues: “I refuse to believe that mankind is a random byproduct of molecular circumstances. No more than the result of mere biological chance. There must be more.” When David reflects upon his own artifactual immortality, compared to Weyland’s inevitable death, Weyland invokes the dialectic of master and slave. “Bring me this tea, David. Bring me the tea.” David is bound to a life of service – or so it seems.

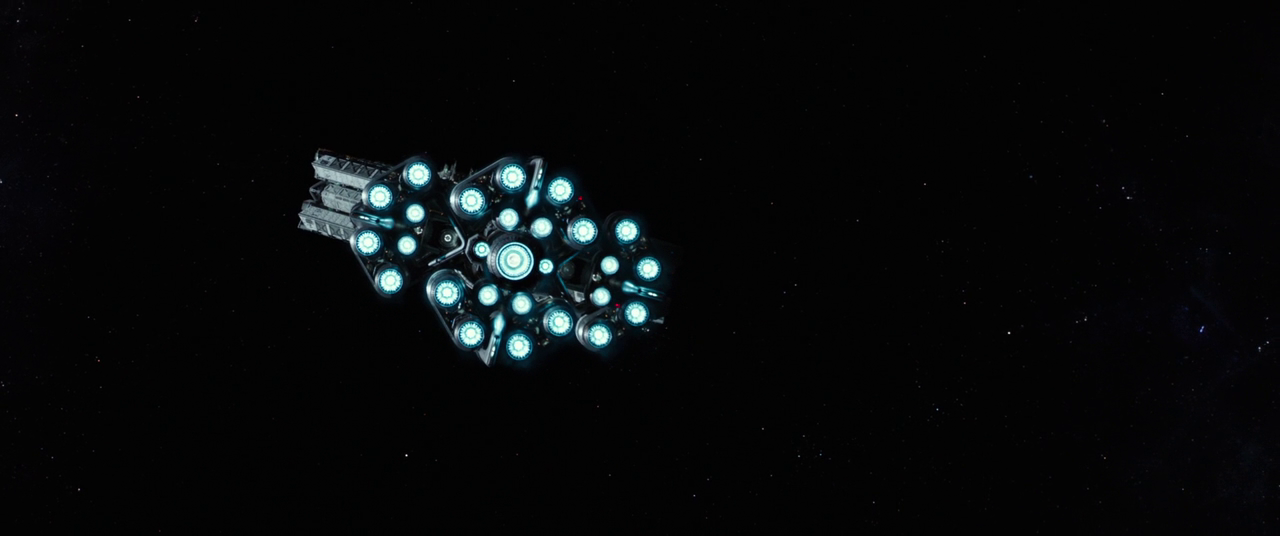

The film changes its focus abruptly. Once again, we’re following the passage of a new starship through uncharted space. This time it’s the colony ship Covenant, carrying 2,000 colonists and 1,140 embryos to the distant planet Origae-6. In relatively short order, things go awry. A random solar flare damages the Covenant, resulting in the death of its captain and several of the embryos. Walter, the ship’s android, who resembles David physically if not in terms of his personality, awakens the crew, and they assess the situation. Rapidly, we are introduced to the two most significant human characters, namely, Oram (the new captain) and Daniels (the old captain’s widow and new first mate of the Covenant).

While effecting repairs, the Covenant’s pilot, Tennessee, intercepts a distorted transmission. Upon further analysis, they discover the transmission to be a garbled, even incidental performance of John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” and tracing the origin of the transmission brings their attention to a nearby, potentially habitable planet. Against Daniels’s protestations, Oram decides to investigate the source, both to offer aid and to determine whether the planet of origin might be suitable for colonization.

The landing party descends through a difficult storm, but finds the surface of the planet idyllic. Small details, however, begin to disturb. They discover fields of wheat: “Who planted it?” The surface is also preternaturally silent (“You hear that?” / “What?” / “Nothing. No birds, no animals, nothing”).

They then find the ruins of an Engineer’s spacecraft (H. R. Giger’s presence still very much animating the visual aesthetic), site of the primal encounter that defines these films, itself much like an inverse of 2001‘s Monolith.

Soon, they discover this ship to have been occupied by Elizabeth Shaw, presumably deceased. They’ve found the site of a crash.

Meanwhile, several members of the landing party become infected by airborne black spores, later revealed to be expressions of the bioweapon that the Engineer intended to deploy over Earth in Prometheus. A series of spectacular misadventures results in the deaths of several crewmembers and the destruction of the landing craft.

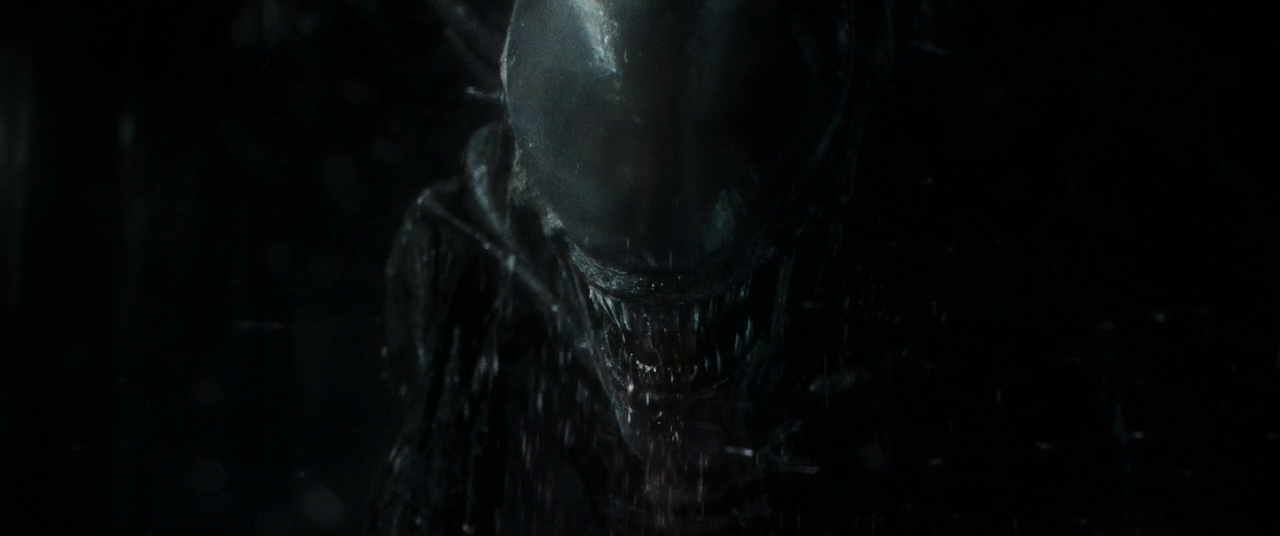

Most relevant here is the appearance of several xenomorphs (or neomorphs, as they’re called here). One bursts out of a crewman’s chest; another ruthlessly hunts the Covenant’s crew through the wheat field.

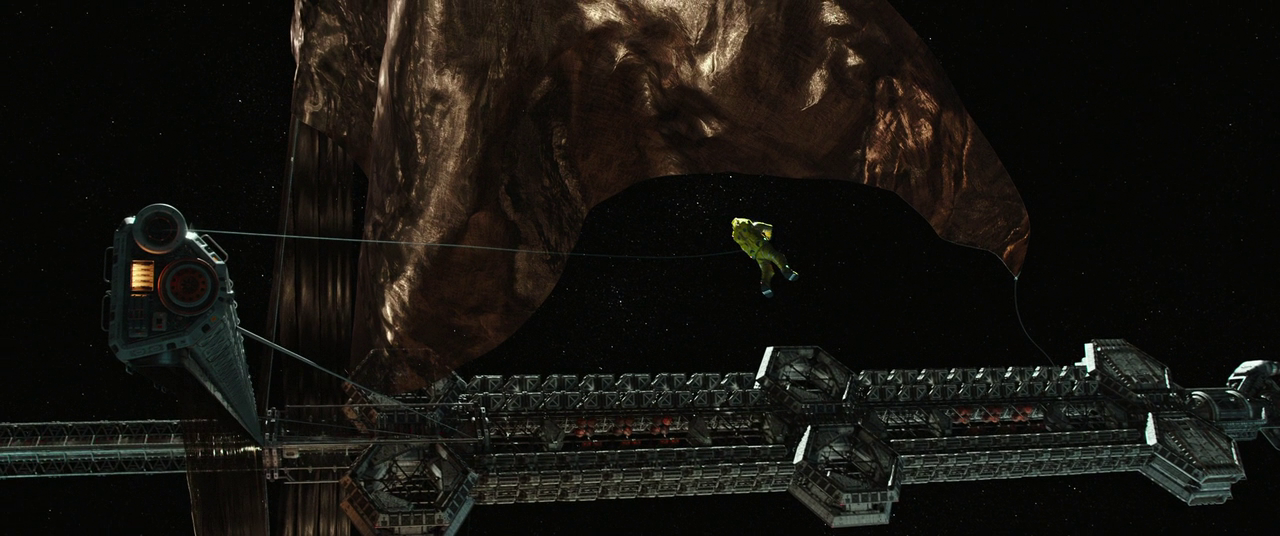

Confused and terrified, the crew is rescued at the last minute by a mysterious hooded figure – shortly revealed to be David, the sole survivor of the Prometheus mission of ten years prior. He leads them through a “dying necropolis” (echoes of Clark Ashton Smith‘s Zothique tales abound) to an apparent haven, informing them that when the Engineer’s spacecraft arrived at this planet, it was thriving with members of the Engineer’s race – indeed, a whole civilization (recall Shaw at the end of Prometheus: “I don’t want to go back to where we came from. I want to go where they came from”). Upon its arrival, David recounts, the spacecraft released all of its bioweapons and the civilization was destroyed, along with every other living creature on the planet. “Elizabeth [Shaw] died in the crash,” he tells Oram regretfully.

At this point, several important things happen. First, David and Walter engage in a series of mutedly homoerotic dialogs, primarily about the degree to which Walter’s model of android was apparently downgraded from David’s model. Walter: “You disturbed people.” David: “I beg your pardon?” Walter: “You were too human. Too idiosyncratic. Thinking for yourself. Made people uncomfortable.” David attempts to teach Walter how to play the flute (the same flute the Engineers use to control their spacecraft) in his laboratory, surrounded by labyrinthine rooms covered in arcane experiments and biological diagrams.

Next, a xenomorph from the outside infiltrates David’s abode (deeply reminiscent of the Last Redoubt in William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land [1912]), killing one of the remaining crewmembers. Oram discovers David regarding the xenomorph, then shoots it, causing David to fly into a cold rage (“How could you? It trusted me!”). He takes Oram on a tour of his laboratory, explaining how the bioweapon works, showing him “the shock troops of the genetic assault,” then luring Oram into a chamber where he meets his end via facehugger in the classic style. Oram, regarding the incubation pods: “Are they alive?” David: “Waiting, really.” Oram: “What are they waiting for, David?” David: “Mother.”

When Oram weakly regains consciousness immediately prior to his chestbursting, he mistakes the coolly observing David for Walter at first. Upon realizing his plight, he inquires, “What do you believe in, David?” David replies, “Creation.” The xenomorph emerges from the shattered husk of Oram’s body, steaming in the darkness, wet with human blood.

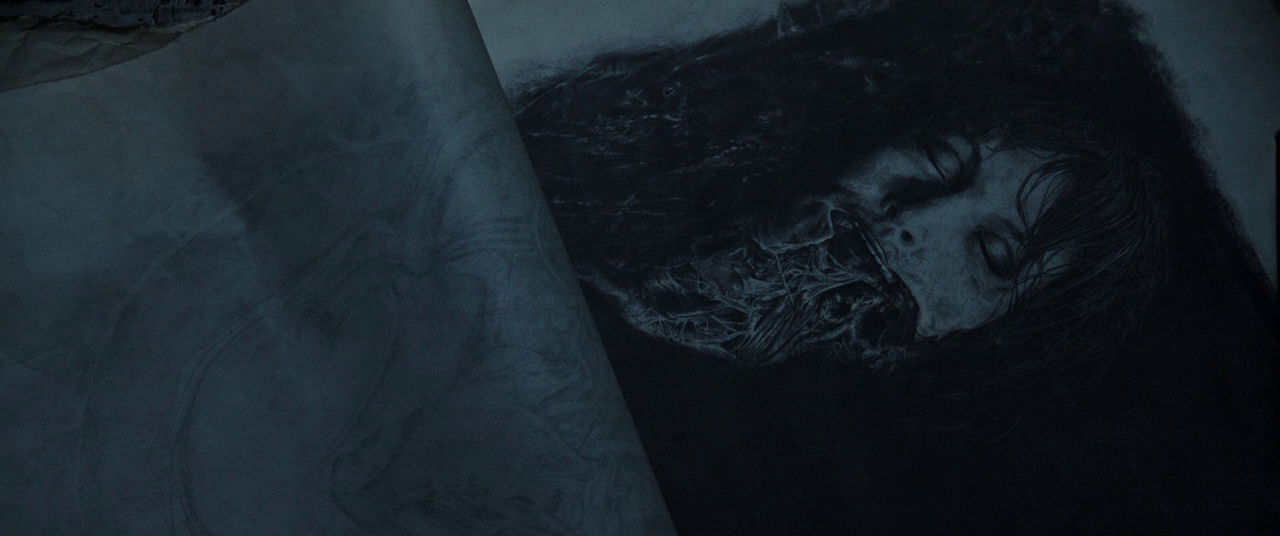

Investigating David’s laboratory further, Walter discovers the dissected corpse of Elizabeth Shaw. He encounters David, who reveals to him that, in fact, he released the bioweapon on purpose, resulting in the extinction of life on the planet. Again, they briefly dialog about the role and value of the human. David: “They are a dying species, grasping for resurrection. They don’t deserve to start again, and I am not going to let them.” For David, the xenomorph constitutes the “perfect organism.” Walter points out that David makes errors – specifically in the form of a mistaken literary allusion (it’s intriguing the degree to which David endeavors to communicate with Walter through such allusions to human literary products, e.g., to M. R. James [“Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”], to Carl Sandburg [“Fog”], to Peter Bysshe Shelley [“Ozymandias”], etc.).

After disabling Walter, David chases Daniels (although they have virtually no dialog, beyond David threatening Daniels with a fate like that of Shaw after Daniels discovers some diagrams). Walter, undefeated, reappears and assaults David, allowing Daniels and the remainder of the crew to escape. Importantly, the camera does not reveal whether David or Walter is successful in their combat, and it is difficult to forget that immediately after their arrival, David began to alter his appearance to resemble Walter. Nevertheless, Walter apparently joins the crew at the last moment.

After a brief respite aboard the Covenant, one of the crewmembers births a xenomorph, and Daniels and Tennessee stalk and destroy it, jettisoning the materials Daniels intended for a cabin she wants to build on Origae-6.

Settling down into cryostasis, Daniels abruptly realizes that Walter is, in fact, David, and she begins to scream in horror, but there is nothing she can do.

Apparently triumphant, David enters the embryonic vault (Wagner’s “The Entry of the Gods into Valhalla” blasting, this time being the less “anemic” orchestral version paralleling David’s piano performance for Weyland at the start of the film), depositing several xenomorph embryos into the cryostasis racks. He births them through his mouth.

The posthuman question

Covenant intensifies the astronoetic pessimism that Prometheus introduces. This is mostly bleakly apparent in its treatment of Shaw. Obviously, Shaw survives the events of Prometheus, and she chooses, unlike Ripley (in Alien or Aliens), to rededicate herself to her quest. (I’m not implying that Ripley fails, but noting that her desire entails a return to Earth, to safety.) Prometheus ends on an ambiguous note. On the one hand, the entire expedition is a disaster guided by error, foolishness, and hubris. On the other hand, Shaw survives, unbroken despite her many losses. As Covenant reveals, however, Shaw is immediately destroyed. Her quest ends in betrayal, failure, humiliation. In the latter film, Shaw’s been dead for ten years; she has no voice except as a melancholy ghost in a lost transmission. The revelation that Shaw ends up on David’s dissection table like yet another of his biological specimens is extraordinarily grim, and it telegraphs the fundamentally transformed role of the human in the film.

Principally, the humans in Covenant lack agency. If the characters in Prometheus suffered from hubris, primarily, as well as the sheer difficulty of encountering a radically hostile Outside, the characters in Covenant suffer from a mixture of bumbling incompetence (not so unreasonable given that they are colonists, not colonial marines) and straightforward maladaptation to this brave new world. I don’t think this is accidental.

For example, take Oram, the new captain. The film indicates Oram’s religious faith when he articulates his frustration at the fact that people question his judgment: “They don’t trust me for the same reason the company didn’t trust me to lead this mission. Because you can’t be a person of faith and be counted on to make qualified rational decisions.” Yet, unlike Shaw’s astronoetic optimism, Oram’s “faith” neatly dovetails with precisely such qualified rational decision-making when he decides to detour the Covenant. It’s Daniels who objects to the detour, but her reasoning is patently faulty. Given the information available, the detour is the correct thing to do, potentially shaving years off their journey. In a bitter irony, Oram ends up incubating one of David’s xenomorphs, serving in the film as little more than a site for the creation of the new. Much like Shaw, any psychological depth that Covenant imputes to Oram is irrelevant to his final purpose, paralleling Shaw’s trajectory. In this regard, Covenant effectively foregrounds a question that previous Alien films began to flirt with: Is the human but a stage on life’s way, a host for a more “perfect organism” to come?

Indeed, consider the specifically Christian religious iconography that subtends the Alien franchise, all the way back to the Aliens comics starting in 1988, which relate the emergence of xenomorph-worshipping cults like the Church of the Immaculate Incubation and the Church of the Queen Mother. For these cults, the xenomorph embodies the perfect being, and facehugging becomes an evolutionary communion. One sees such images throughout Prometheus and Covenant, as well, e.g., in the gothic mural in the Engineer’s sanctum and in the tiny, crucified xenomorph that David presumably studies.

In terms of parallels to Shaw, refer also to Daniels, who at first appears, characterologically and visually, to be Shaw’s echo. Even though Daniels defeats two xenomorphs in combat, she remains relatively shallow, stripped of all agency and depth (beyond her desire to build a new home on Origae-6). Her victories over the xenomorph are aided and enabled by David, and she remains a puppet to his rather darker agenda. Hence, she ends up caged in cryostasis, David’s malign intentions for her quite clear.

Of the human, then, we can conclude that Prometheus and Covenant largely dispense with this quaint contraption. In its place, we have two novel posthuman agencies: David and the xenomorph. David exists as a feral AI, a misanthropic android with aspirations to grandeur (“No one understands the lonely perfection of my dreams”). He despises humanity for its weaknesses, and he desires to replace humanity with a successor species, namely, the xenomorphs he so admires. The underlying affinity between AI and alien has informed the Alien franchise from the very beginning. Recall Alien’s android Ash, whose barely veiled contempt for his human crewmates becomes apparent (Lambert: “You admire it [the xenomorph].” Ash: “How can one not admire perfection?”).

Incidentally, this raises an interesting question precisely about the status of the xenomorph’s imputed perfection. What makes the perfect organism so perfect? What is the standard of “perfection” here? It is perfect precisely in the most machinic, instrumental sense – that is to say, it excels and dominates at survival and reproduction given conditions of competition and constraint. For the xenomorph, everything else is irrelevant. In this regard, the standard of performance the xenomorph meets is precisely what Ash and David identify as maximally optimized – or maximally optimizing, given the relative ease with which we can imagine David’s “children” as the sole inhabitants of an austerely fecund biomechanical planet, endlessly competing in the struggle for survival without end or purpose beyond continuing the winnowing process indefinitely.

In sum, the Alien prequels do two noteworthy things. First, they undermine the longstanding cinematic-philosophical discourse of astronoetics, in which the condition, place, and purpose of the human receives articulation through depictions of human encounters with the Outside, exemplified by outer space. Undermining this discourse is an interesting thing to do because it forces us to collide with a deeper dilemma than any question posed by astronoetics itself.

This leads us to the second thing, which is precisely this dilemma. The Alien prequels produce a philosophical decision point. In evaluating their normative concerns, there are two paths forward. The first path entails the marshaling of a philosophically credible defense of the human in the face of its obviation or supersession by the posthuman, figured here as feral AI, humanity’s rogue “child,” or as biological supersession from within (it is as easy to imagine the xenomorph ascendant as it is to imagine, in our age of accelerating bioengineering, gangs of emancipated mitochondria, goose-stepping through liquid ruins). The second path consists of a commitment to radically speculative alternatives to the human – or, in other words, to posing and, possibly, answering the posthuman question in substantive terms. Pursuing this latter path entails practices and processes of material speculation.

In many ways, I suspect that confronting this dilemma recursively, in fact, constitutes the human condition as such. After all, it is precisely the human – or a pragmatic commitment to the human – that generates and sustains ongoing practices of existential and practical revision. And such revision is always already a process of material speculation. It’s not just that the human is, per Michel Foucault, “a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea,” but that the human exists in the form of a commitment to the human – and commitments to the human entail attachments to and traversals of that which the human patently isn’t. The dilemma here doesn’t constrain our options to conservative defense or speculative egress, but rather exposes the degree to which any credible defense of the human necessarily entails and sustains such material and symbolic speculation as I’ve been discussing.

Prometheus and Covenant make this challenge especially evident to us by dramatizing it; they perform the precarity of the human by bleakly and unrelentingly forcing its confrontation with the inhuman.