Like the Hawksmoor churches serve as privileged reference points for a uniquely British psychogeography, so the Winchester House will be the first such reference point for us.

It’s the first, not the earliest, because the fundamental structure of American psychogeography consists of displacement. Of course, I mean displacement in every sense the word implies – psychic, spatial, temporal – and the Winchester House is the architectural materialization of displacement.

Where British psychogeography mines, or undermines, the strata of time, American psychogeography endeavors to occlude time itself.

British psychogeography seeks to enter, explore, or operationalize the rural or urban wyrd. Consider the temporal echoes and whorls of Alan Garner’s novel Red Shift (1973), in which Roman Britain, the English Civil War, and the 1970s are all refracted through the landscape surrounding Mow Cop in Cheshire and thereby focused into a primitive stone axehead that emerges from the deep past. The axehead is alien, electric, timeless. You might say it’s haunted, or, better yet, that it is itself a kind of haunting, like the old bone whistle (“Quis est iste qui venit”) that Professor Parkins finds on a desolate shore, or the lost Anglian crown that dooms its discoverer. Landscape here serves as a medium – like the shaded, transparent material of a film, or a ghost – through which the past haunts the present.

Recall the end of an episode of Mackenzie Crook’s The Detectorists (S2E6, 2015), where the sound of a horseman chasing a fleeing Anglo-Saxon priest carries through time, somehow drawing attention to a buried aestel, or the somewhat less portentous ending of a different episode (S1E6, 2014), in which the disembodied perspective of the camera sinks into the loam, revealing it to be studded with artifacts and the ruins of a burial ship. The scene is simultaneously earthy and vertiginous. Something in the land takes hold, looking up at you from the dirt like an upturned eye, stirring like the barrow wight of “Randalls Round.” It possesses you with its beautiful and eerie power. It makes you weep, even if you don’t know why.

The past isn’t prologue, but present. Blake’s Albion, Penda, Sexred, Jack the Ripper – they’re walking still. You might even meet one, if you learn how to see where you are, which often involves unseeing where you thought you were.

By contrast, American psychogeography occludes its wyrd, or tries to, and its strategies of occlusion manifest the fundamental psychic weirdness of the American landscape. Displacement and occlusion – these are the watchwords of an American psychogeography.

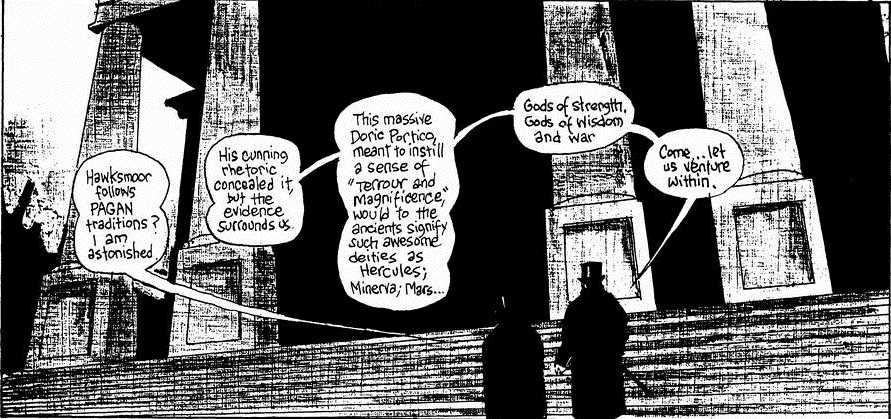

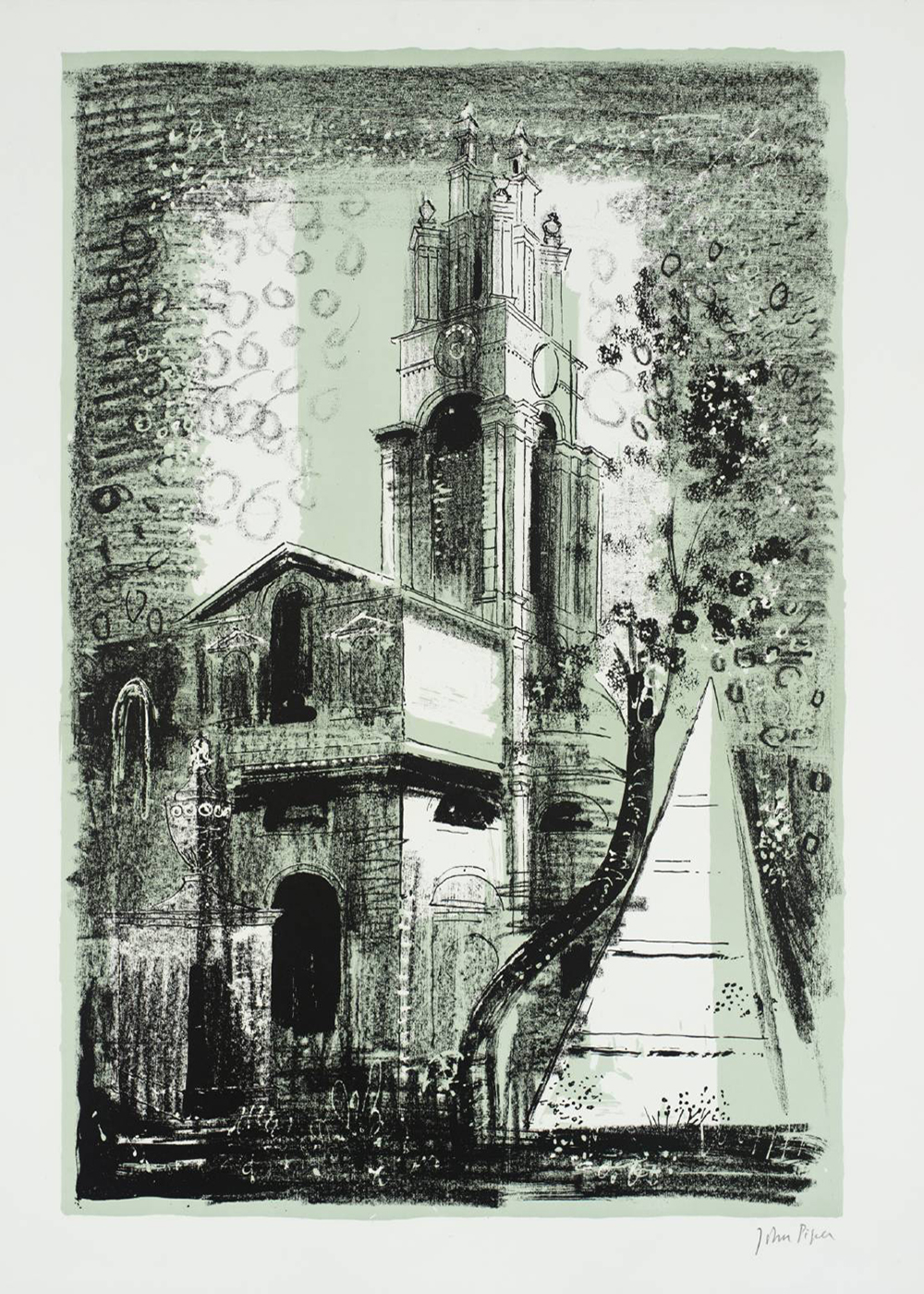

Consider these characterizations of the Hawksmoor churches:

[…] the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor soon invade the consciousness, the charting instinct. Eight churches give us the enclosure, the shape of the fear; – built for early century optimism, erected over a fen of undisclosed horrors, white stones laid upon the mud and dust. In this air certain hungers were activated that have yet to be pacified; no turning back, as Yeats claims: ‘the stones once set up traffic with the enemy.’ […] Each church is an enclosure of forces, a trap, a sight-block, a raised place with an unacknowledged influence over events created within the shadow-lines of their towers. […] There is no Chartres or Salisbury feel, with the church as the excuse for everything else. It shocks every time you glimpse one of the towers. They are shunned. Their strength is hybrid, awkward: an admix of Egyptian and Greek source matter – curiosities discovered in engraved library plates. Necropolis Culture. Behemoths from the Zoo of Abortions. Botched Sphinx experiments.

(Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat: A Book of Dead Hamlets [1975])

It is only the Darknesse that can give trew Formed to our Work and trew Perspective to our Fabrick, for there is no Light without Darknesse and no Substance without Shaddowe (and I turn this Thought over in my Mind: what Life is there which is not a Portmanteau of Shaddowes and Chimeras?). […] I am not a slave of Geometricall Beauty, I must build what is most Sollemn and Awefull. […] Joseph of Arimathea, a Magician who had embalmed the Body of their Christ, was sent into Britain and was much honoured by the Druides; he it was who founded the first Church of the Christians in Glastonbury where St Patrick, the first Abbot, was entomb’d beneath a stone Pyramidde: for these Christians got a Footing so soon in Britain because of the Power of the Druids who were so eminent and because of the History of Magick. Thus under where the Cathedral Church of Bath now stands there was a Temple erected to Moloch, or the Straw Man; Astarte’s Temple stood where Paul’s is now, and the Britains held it in great Veneration; and where the Abbey of Westminster now stands there was erected the Temple of Anubis. And in time my own Churches will rise to join them, and Darknesse will call out for more Darknesse. In this Rationall and mechanicall Age there are those who call Daemons mere Bugs or Chimeras and if such People will believe in Mr Hobbes, the Greshamites and other such gee-gaws, who can help it? They must not be contradicted, and they are resolved not to be perswaded; I address myself to Mysteries infinitely more Sacred and, in Confederacy with the Guardian Spirits of the Earth, I place Stone upon Stone in Spittle-Fields, in Limehouse and in Wapping.

(Peter Ackroyd, Hawksmoor [1985])

(Alan Moore, From Hell, [1989-1998])

What the Hawksmoor churches embody is a set of distinctive buildings that ultimately evoke a system of occult relations. They manifest ley lines of historical strangeness that sketch out the map of a darker London hiding inside London, or what Arthur Machen called “London incognita.” The churches themselves – St Alfege’s Church, Greenwich; St George’s Church, Bloomsbury; Christ Church, Spitalfields; St George in the East, Wapping; St Mary Woolnoth; and St Anne’s Limehouse – protrude into the landscape from below like roofing nails piercing the sole of an old boot. They contradict the tenets of sacred (Christian) architecture. Various British psychogeographers have mapped out the positions of the churches in relation to each other. Sinclair, Ackroyd, and Moore all suggest that Hawksmoor was inscribing a glyph upon the world, that the design and placement of the churches form key ingredients of a spell made manifest in architecture – in blood, stone, and darkness.

There’s always been something fundamentally eerie about architecture.

Every architectural work is mostly emptiness, but, unlike an open field, the emptiness inside is the emptiness of a built enclosure. It is tortured into shape. At the very least, to have a work of architecture, it’s necessary to have extensional constraints (e.g., arches, pillars, or walls), but it is equally necessary to have voidal artifacts and passages (e.g., aisles, doorways, or spandrels). Architecture is as much about the organization of empty space as it is the assembly of various materials.

A work of architecture is also always both a manifestation and a ward. It remains underdetermined whether architecture as such tries to bring something about, or to keep something out. Perhaps both. In this regard, the primordial work of architecture isn’t one of the Seven Wonders, or some grand cathedral, but the Labyrinth at Knossos. Winding corridors manifest a kind of lair from which egress becomes impossible. You think you’ve gotten out, but then you turn a corner and find yourself still within its walls. The Labyrinth expands with every construction site, from Göbekli Tepe to the McMansion next door. Every building is just an echo of the megalithic maze lurking at the origin of the built world. As with the Labyrinth, there’s always a monster inside the mystery.

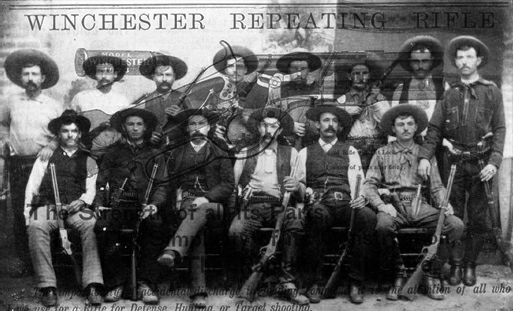

Sarah Winchester (1840 – 1922) was the widow of William Wirt Winchester, treasurer of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company and son of Oliver Winchester, the company’s major stockholder. When William died in 1881 at the age of 44, Sarah became one of the wealthiest women in the world.

The Winchester fortune was a blood harvest.

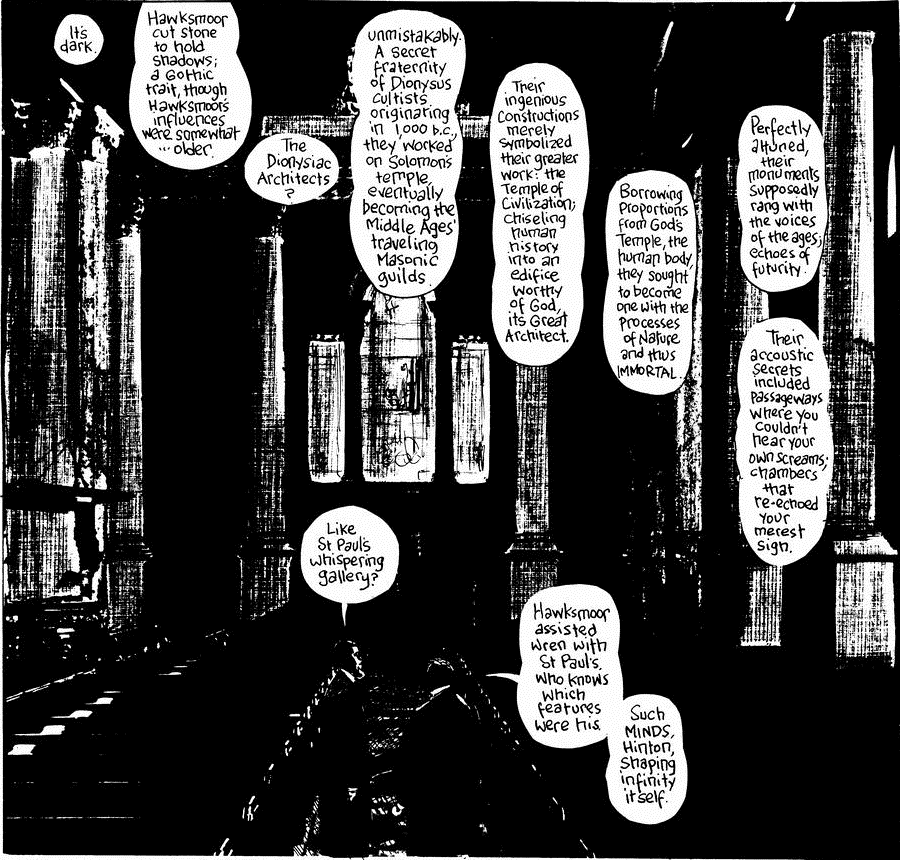

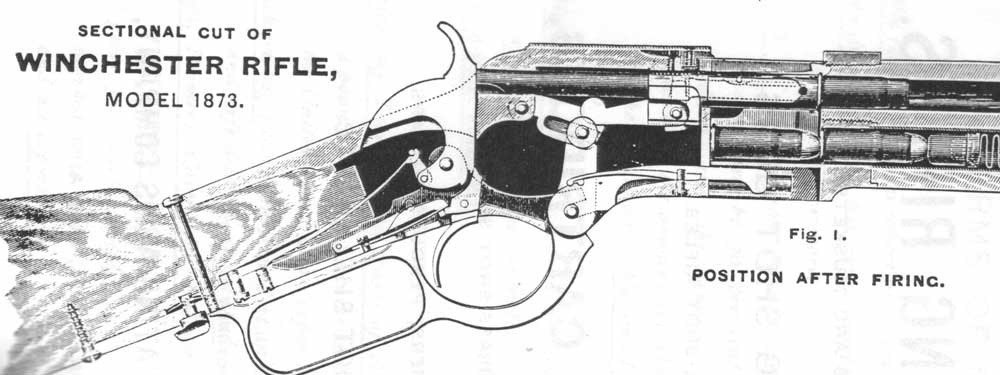

In 1866, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company released the Model 1866, a lever-action repeating rifle that received a functional upgrade in 1873. The Model 1873 – known colloquially as “the Gun that Won the West” – was one of the most popular rifles of its day, and it remained in active production and widespread use until 1923. Characteristic of Winchester rifles was their accuracy, ease of use, and rate of fire. Hundreds of thousands of Model 1873s were produced before the turn of the century alone. In Cartridges of the World (2012), Frank C. Barnes writes that the .44-40 cartridge used in the Model 1873 has probably “killed more game, large and small, and more people, good and bad, than any other commercial cartridge ever developed” (95).

It was the rifle of choice for the Texas Rangers and for Buffalo Bill, who wrote this almost metaphysical testimony for the Winchester 1875 catalogue:

I have been using and have thoroughly tested your latest improved rifle. Allow me to say that I have tried and used nearly every kind of gun made in the United States, and for general hunting, or Indian fighting, I pronounce your improved Winchester the boss. An Indian will give more for one of your guns than any other gun he can get.

By now, many people know the basic outlines of the story. Sarah Winchester, a committed Spiritualist, held a séance in which her late husband, now a resident of hell, told her that the ghosts of all those killed by the Model 1873 would haunt her forever. To avoid them she would have to travel far away and build a house so confusing it could afford Sarah a little peace by losing the ghosts in its crooked corridors and dead-end stairways. So Sarah moved to San Jose, where she built the Winchester House, a sprawling architectural bad dream, the design of which she revised until the day she died.

Or perhaps you’ve encountered the variation in which Sarah went to see a fortuneteller some time after William’s death. The old crone pulled secrets from the ether and told Sarah she’s the victim of a curse, the Winchester curse. No family can enable the spilling of so much blood on the land without astral consequences. The fortuneteller said, You must undertake a great work in Babylon. You must go and build a house for the dead where you will live until the end of your days. Build a mansion for the unquiet spectral horde, and if you ever cease laboring upon it, they will drag you down into the hell your family so liberally populated.

In either case, Sarah’s encounter with the spirit world sent her packing off to California, where she promptly began construction.

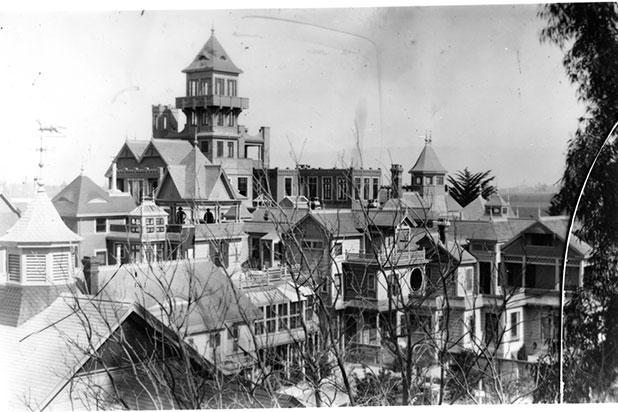

In San Jose, Sarah became a recluse (famously, she rejected opportunities to host two sitting presidents – McKinley and Roosevelt), wearing black as if in perpetual mourning. From 1866 onward, the Winchester House metastasized, expanding and contracting like an animal whose breaths took years. It contains approximately one and a half miles of halls and stairways. Doors open onto internal abysses. Windows filled with Tiffany glass face brick walls. The Winchester House has more than 10,000 external windows. One commentator writes, “The house is, in a way, a form of automatic writing, a stream of consciousness made spatial.” In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake leveled portions of the house that Sarah simply walled up. A seven story tower collapsed. One caretaker noted, “The top three stories got knocked off [during the earthquake]. So there’s steps that just go all the way up and hit the ceiling. Or you open a door and it just falls three floors.”

It’s actually true that she personally designed and oversaw the endless construction of the Winchester House. Indeed, she may be one of architectural history’s forgotten and neglected innovators. She probably invented the indoor window crank and wool insulation. Women were not allowed to train as architects at the time, which may account for some of the Winchester House’s less felicitous idiosyncrasies. She was relentlessly marginalized and misrepresented by yellow journalists – not only because of her commitment to the house, but also in no small part due to the changing public image of the role played by repeating arms in the American Indian Wars. In fact, the rumors (largely unsubstantiated – although historian Ralph Rambo states that Sarah was probably a Theosophist) of her dalliance with Spiritualism, of the occult aura of the Winchester House, including the Winchester curse itself, only first appeared in the papers starting in 1895. Factually, however, there is no evidence to suggest that Sarah felt any concern whatsoever about the death toll of the Model 1873, nor any uncertainty about the blood money that made her fortune.

And why would she? After all, the American gun gods form a cruel, but lucrative pantheon, like a numinous cartel. Stories about the miracles and tragedies wrought by our divinities Colt, Remington, Smith & Wesson (a god with two faces, dyophysitism in metal), and Winchester are legion. The colors of the gods are blue and silver and red – especially red, endlessly flowing crimson rivers, bearing clots and corpses. We give them more hearts than the Aztecs fed to Tezcatlipoca, the god of night, sorcery, and “the north” (perhaps where Sarah built the Winchester House). In return, guns work spells – violent action at a distance. They transubstantiate miles into seconds, ill intent into ballistic reports, and lives into land. Like buzzing lead hornets, they replace the need for us to speak, and they give voices to the new gods. Every gunshot heard in the night is a report on the state of the awesome and terrible myths we are making. A needful affirmation underwriting the American mind, the unconscious assurance that somewhere, a gun is being fired…

Whether or not Sarah Winchester felt haunted, or was haunted – whether or not she intended her construction project to corral or trap devils, or fears, or ghosts, or worries – the Winchester House is a prime realization of the displacement at the heart of American psychogeography.

The structure of the building makes manifest the displacement that works of architecture always perform, true, but it doesn’t simply enclose and rearrange space for some functional or monumental purpose. The Winchester House is secretive and tangled. They’ve discovered whole unopened rooms as late as 2014. In 1975, workers found a locked empty room containing two chairs and an old phonograph. Sarah’s “blue room,” where she is rumored to have held regular séances, has yet to be discovered. Perhaps it’s hiding. It’s not too difficult to imagine that the house is still building and unbuilding itself, somehow, in order to make room for the ongoing procession of sacrificial victims. The Winchester House has a big appetite.

Look at it. It’s simultaneously angular and bloated, predatory and sprawling, like an overfed predator eying passersby from behind its many fences and hedges. It’s hiding in the bushes, one of the Bay Area’s first serial killers, still at large.

To paraphrase Shirley Jackson, the Winchester House, not sane, stands alone – albeit adjacent to yogurt shops and the corpses of dead malls – holding darkness within. Unlike Hill House, however, whatever walks Winchester House doesn’t walk alone. There are whole tribes in there, all the peoples whose violent erasure forms the haunted history of the American gun. Even the House of Usher had the good grace to fall down, eventually.

It’s no surprise that the recent film Winchester (2018) avoids reflecting on anything except the spook show element.

On the one hand, it’s a painful, total failure of a film. It follows Dr. Eric Price, hired by the Winchester Company to assess Sarah’s mental health. (Her real doctor was a rare female physician named Euthanasia Meade.) Price discovers a house full of ghosts. Although many of these ghosts are depicted as eerie subaltern shades, the film stays quiet about anything to do with complicity, inheritance, guilt, or remorse, much less the mythic iconography of the gun itself. The chief antagonist is ultimately revealed to be an aggrieved (dead) Confederate named Benjamin Block. We can see immediately how even a film about the Winchester House can’t avoid embodying the same displacements in its core structure. It’s as if the film replicates occlusions found in the very work of architecture it uses as its setting. It’s a stairway to nowhere.

On the other hand, Winchester’s denouement is ironically perfect. Price, who had previously been shot by a Winchester rifle before being impossibly revived, carries with him the very bullet that wounded him. It’s this magic bullet – doubtlessly a .44-40 – with which Price eventually shoots Block’s vengeful ghost, thereby dispelling it forever. This resolution reveals the extent to which guns have pride of place in our collective imagination. When faced with the angry ghosts of gun violence – who also end up carefully filtered so as to avoid acknowledging the real historical effects and use of the American gun – the only speculative solution that comes to mind is to shoot them. If specters from the past have the temerity to assert themselves, we’ll gun them down. If we already gunned them down once, we’ll do it again. Even dying in a hail of gunfire isn’t enough to stop it from happening to you again. You’ll run out of ectoplasm before we run out of bullets. There are almost certainly trillions of rounds of ammunition just waiting around to be fired right now. It’s not for nothing that the Model 1873 was a repeating rifle, animated by a mechanism of repetition inside that allows its wielder to fire over and over again.

What was Sarah actually trying to do with the Winchester House? Is it a material condensation of grief or guilt? Was it nothing more than an architectural plaything for an eccentric heiress? One biographer proposes that the constant construction project was actually a conscious or unconscious excuse Sarah used to avoid inviting unwanted relatives to visit. Or is it really a labyrinth for swarms of troubled ghosts? Maybe we could think of the house itself as a kind of esoteric gun, built to fire a psychic bullet deep into the red, wet meat of the American body politic. It’s a message from Sarah to you or me. A coded message in a bullet. Supposedly, bullets can be inscribed with the names of their targets to ensure they fire true. The bullet cuts through time in an unusual fashion, traveling in a long, curving arc that breaks with traditional Euclidean geometries and moves far too slowly for anyone to perceive directly. You just have to figure out what it says.

It has been suggested that the Winchester House is an algorithm displayed in spatial terms, that one of Sarah’s guides in the ongoing process of its design was the Fibonacci spiral, or else privately derived experimental number sequences intended to help instantiate or traverse four-dimensional space. After all, she was educated by Rosicrucian philosophers. If you walked the dead-end stairways properly – placing your feet in the right order, adjusting your gait to the dimensionality of Tindalos – you could find yourself in entirely new partitions and wings.

In this sense, the Winchester House is more like an Escher print than it is a building in any traditional sense. It’s an American labyrinth, a stone and wood fractal that hides from the surrounding landscape like a camouflaged spider, waiting to strike. It shuttles psychic heat off into the nth dimension, only accessible through strange dérives. By this point, most of the house is no longer visible, but located stepwise. Many visitors report shadows lurking in the corners of their vision, or figures in motion who turn corners impossibly fast and then disappear. Who lives there now? Who is this who is coming – or going? The visible Winchester House today is a carnival attraction, a cotton candy corn spookhouse – but perhaps this only seems to be true because the vast majority of it spills over into a witch dimension.

This tells you everything you need to know to get started with an American psychogeography.

Imagine walking through the Winchester House In the middle of a hot, preternaturally still summer afternoon. The background noise of the nearby highway fades away as you pass a corridor you swear you’ve seen a thousand times. But something is different. It never looked quite so long before. You slow, then stop. Something imperceptibly vertiginous catches your eye, like a strip of film twisting up inside an old-fashioned projector. Cigarette burns start screeching by. When you step into the hall, your foot lands on the wall, just below the gilt chair rail, but, somehow, your leg isn’t bending impossibly. You take another step forward, driven by a dark curiosity that beckons you deeper inside. You hear someone breathing nearby. It sounds like it’s coming from inside the wall.

The sleeper awakens. You live in the witch house now. This is not an exit.