The concept has a long and varied career. As a word, it comes from the Latin noun obiectum, referring generically to a tangible thing that’s perceptible by the mind or the senses, to “something that occurs in front of,” or, more abstractly, to “that which is placed before” (i.e., before a perspective or a vantage point). In this regard, obiectum derives from the verb obiciō, meaning “I oppose” or (most literally) “I throw against,” which illustrates its original use: accusation, charges, reproach. It’s interesting to contrast this active, oppositional sense of the word with the grammatical sense that emerges fully in the modern period. The object of a sentence, after all, is the grammatical element acted upon by the subject. Objects cannot act (or else they become subjects); they are passive recipients of action.

In the history of Western philosophy, the subject-object distinction also figures quite prominently. For a philosopher like Johann Fichte, the subject (das Ich) refers to the active principle of intellection embodied by consciousness or the mind, and, according to Fichte, subjects bootstrap themselves into existence by overcoming objects (das Nicht-Ich). Less abstractly, on this account, human subjects implement themselves and realize their intentions or projects by dominating an object world. Indeed, for Fichte (and many others), a subject becomes a subject in the first place – or individuates itself – precisely by means of enacting and enforcing this distinction. Hence, objects are characterized as materially or metaphysically passive, as “dead matter” or inert stuff that functions deterministically or mechanically until a subject actively intervenes.

You can find a similar disdain for objects explicitly articulated by many philosophers. For example, Francis Bacon, the so-called father of empiricism, aims “to generate and superinduce on a given body a new nature” that exceeds its natural aimlessness or wasteful exorbitance. Likewise, René Descartes, one of the founding figures of modern rationalism, argues that all material objects function as clockwork or hydraulic mechanisms, animated by minds if they are lucky enough to be human bodies but, otherwise, shoved along by vortical eddies. For Bacon and Descartes, the fundamentally inert or passive nature of the object corresponds inversely to the dexterity of the subject – that is to say, to the subject’s innate capacity for administrative direction and manipular control. Dexterity here refers to the power of the subject to command and conquer the objects that populate its object world. The disdain attending such dexterity, perhaps, can be traced back to the almost pathological aversion of the ancient Greeks to any form of dependence or passivity, which was almost always perceived as subordination and weakness.

It is worth noting, however, that objects are not always characterized in this way. For example, in “The Thing” (1971), Martin Heidegger endeavors to subtract the object’s autonomy (or “thingness”) from its constitution as an object. He does this by introducing yet another distinction, the distinction between the object and that which he calls the thing (das Ding). On his account, objects are always relations or representations. They exist relative to a subject, so an object is always functionally or phenomenologically subordinated to its appearance or use. By contrast, the thing is “the cautious and abstemious name for something that is at all.” The thing is independent and self-supporting, he writes, and, while the thing “may become an object if we place it before us,” the thingness of the thing is its autonomy or mute, worldly ipseity, apart from all perception or purpose. Heidegger’s take here is questionable, not because objects can be afforded no autonomy, but because he effectively reduces their autonomy (i.e., the autonomy of das Ding) to the status of an allusion. In other words, Heidegger’s distinction between object and thing appears more to evidence his aversion to the instrumental dimension of objects – that is to say, he voices his antipathy for subjecting objects to any kind of use – than it attends to their manifold or multimodal forms of existence. A horse is a horse, of course, of course; a jug is a jug is a jug. But horses and jugs both embody and inhere in a lot of modes and orders other than their sheer ipseity, as Heidegger’s own reflections ironically testify. In this regard, it’s Bill Brown who picks up Heidegger’s distinction between object and thing and does something rather more interesting with it, by focusing on object failure as an opportunity of sorts: “The story of objects asserting themselves as things, then, is the story of a changed relationship to the human subject and thus the story of how the thing really names less an object than a particular subject-object relation.”

Excursus 1: OOO

I should note here that I’m neither elaborating nor endorsing an object-oriented ontology (OOO) of Graham Harman’s variety. Yes, I am writing about objects, but, as becomes more apparent below, I’m interested in the conjunction or interaction between what the pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce calls objects and their signs, or the penumbra of (conceptual, historical, material, and semiotic) effects attending both. Alternatively, this is what Alfred North Whitehead endeavors to systematize in terms of what he calls actual occasions on the one hand and abstractions on the other (I leave this aside for now, although I’d be remiss not to mention Steven Shaviro’s excellent little monograph The Universe of Things: On Speculative Realism [2014] in this regard). In any case, for Harman, OOO prioritizes the standing or status of the object as a primary, even originary ontological unit. As he writes, “the world is made up of vacuum-sealed objects, each with a sparkling phenomenal interior invaded only now and then by neighboring objects.” On his account, everything that exists exists as some kind of an object, and the world is a collection or gathering of such objects. Furthermore, objects exist completely independently of one another. They occupy “cellars of being where no relation reaches.” Although relations of some indirect (or vicarious, as he says) variety may intervene between objects, every object is ultimately self-sustaining. Any relational or representative interaction is mediated and partial. Accordingly, objects are in no capacity constituted by relations, and nor are they exhausted by the relational frameworks in which they might appear. Harman’s “real objects” stand alone. His rather astute critic Peter Wolfendale (especially in the longform treatment he gives in Object-Oriented Philosophy: The Noumenon’s New Clothes [2014]) levels a rather sharp set of criticisms at Harman (see an abridged version here). The part of Wolfendale’s critique that strikes me most is this: Harman ultimately sneaks constraints and relations into his objects, into his (“allusive”) ontology, but he then fails to admit doing so. Consequently, Harman consistently and systematically relies on a suppressed pivot point between what, in an older vocabulary, would be called noumenal and phenomenal object worlds. For Harman, “real objects cannot touch,” but their dreams or ghosts can – and here we pass into what Wolfendale calls “the borderlands through which they [i.e., Harman’s objects] smuggle causal contraband, or the embassies through which they communicate” (21).

In contrast to the foregoing accounts (although hopefully without being incognizant of them), let’s try approaching the object again.

Definition: An object is an intersection, or a nexus, of various ontological strands. Think of it like a knot consisting of various strands complicated or entangled in a certain way. “Strands” here refers to articulations of the different modes and orders of existence. For example, objects can have a material composition, like an automobile or a tree, consisting of metal and plastic parts or else bark, leaves, and wood. But an automobile or a tree always consists of more intersecting strands than just the physicalist specificity of its material composition. In this regard, automobiles are also products of the history of technics, and their material composition necessarily implies and relies upon complex, temporally extended industrial networks and machinic ecologies. Likewise, trees, in addition to being leafy, execute an ecological function, both as components of forests, which exist at a different ontological scale than any individual tree or group of trees, and as air purifiers, arboreal habitats, carbon sinks, water filters, and much else besides.

Contributing to what an object is, there is also the descriptive apparatus that attends it. The descriptive apparatus consists of semiotic strands, of the contingent, historical penumbra of signs that accompanies an object as it carries on through time, as it gets transacted, transfigured, and translocated. In the received ontological framework – that is to say, on the standard assumption, or how we typically think about these matters, at least when we’re using ordinary language – we tend to think of descriptions of objects as fundamentally separate, or at least separable, from the objects themselves: “A rose by any other name is still a rose.” By contrast, on my account, the descriptive apparatus attending an object is a full-fledged part of that object’s existence. Description is not a supplementary feature of the object. Note how this doesn’t imply that any instance or form of the descriptive apparatus takes precedence or priority over other ontological strands by default. We need to remain absolute particularists about precedence and rank-ordering. The relevant particulars of an object depend on where we are and what we’re trying to do. So we really don’t need to be as resolutely austere as W. V. O. Quine about our ontological commitments. To the contrary, see William Wimsatt’s absolutely outstanding work on precisely this – on levels, perspectives, and “causal thickets.” As he writes, “this is ontology for the tropical rainforest.”

Excursus 2: Peirce

Superficially, Charles Sanders Peirce seems like he disagrees. Again and again, throughout his body of work, objects are consistently characterized as the causes or progenitors of all those signs that recursively attend, depict, and mediate them. As he writes (in a draft version of the “Pragmatism” lectures of 1903), “in all general inquiries about signs nothing is of more lively importance than maintaining a clear and sharp distinction between the object, or professed cause of the sign, and the meaning, or intended effect of it.” He explains further, arguing that there are two kinds of objects, which he calls immediate objects and real objects. Immediate objects are perceptually or symbolically mediated (or “the object as the sign represents it”), whereas “the real object is that same object as it is, in its own mode of being, independent of the sign or any other representation.” On the face of it, then, for Peirce, the descriptive apparatus necessarily differs from the object it attends. In “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” (1878), however, Peirce takes a seemingly different tack: “Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception [emphasis mine] to have. Then, our conception of those effects is the whole of our conception of the object.” In other words, Peirce identifies a conception with the penumbra of effects that such a conception and its object conspiratorially coproduce. It’s certainly true that when Peirce discusses concepts, he characterizes them principally in terms of signs and symbols. That being said, I think Peirce is not trying to provide strict criteria by which we accurately or inaccurately determine which causes produce which effects (this is part of the salutary work of the sciences qua science) as much as he is trying to collapse the traditional understanding of cause and effect into an ongoing, processual conception of causality. Revision is interminable. My point is that, on a broadly pragmatist account, like his (or mine), the autonomy or singularity of an object necessarily implicates the descriptive apparatus attending it. The descriptive apparatus, or the sign, is not an abstract graphemic complex capriciously layered or slapped on top of an object. Certainly, in Peirce’s terms, a sign isn’t such an arbitrary supplement. It may be possible to conceive of objects attended by no descriptive apparatus (just like it is possible to imagine objects that have no physical dimension, like H. P. Lovecraft’s Elder Gods or perfect triangles), but insofar as an object is attended by a descriptive apparatus at all, that descriptive apparatus is a part of the object – effectively and functionally, if not (necessarily) materially. Furthermore, on this view, abstractions of whatever grade or variety are no less objects than concretions are.

So what does it mean to say that objects act?

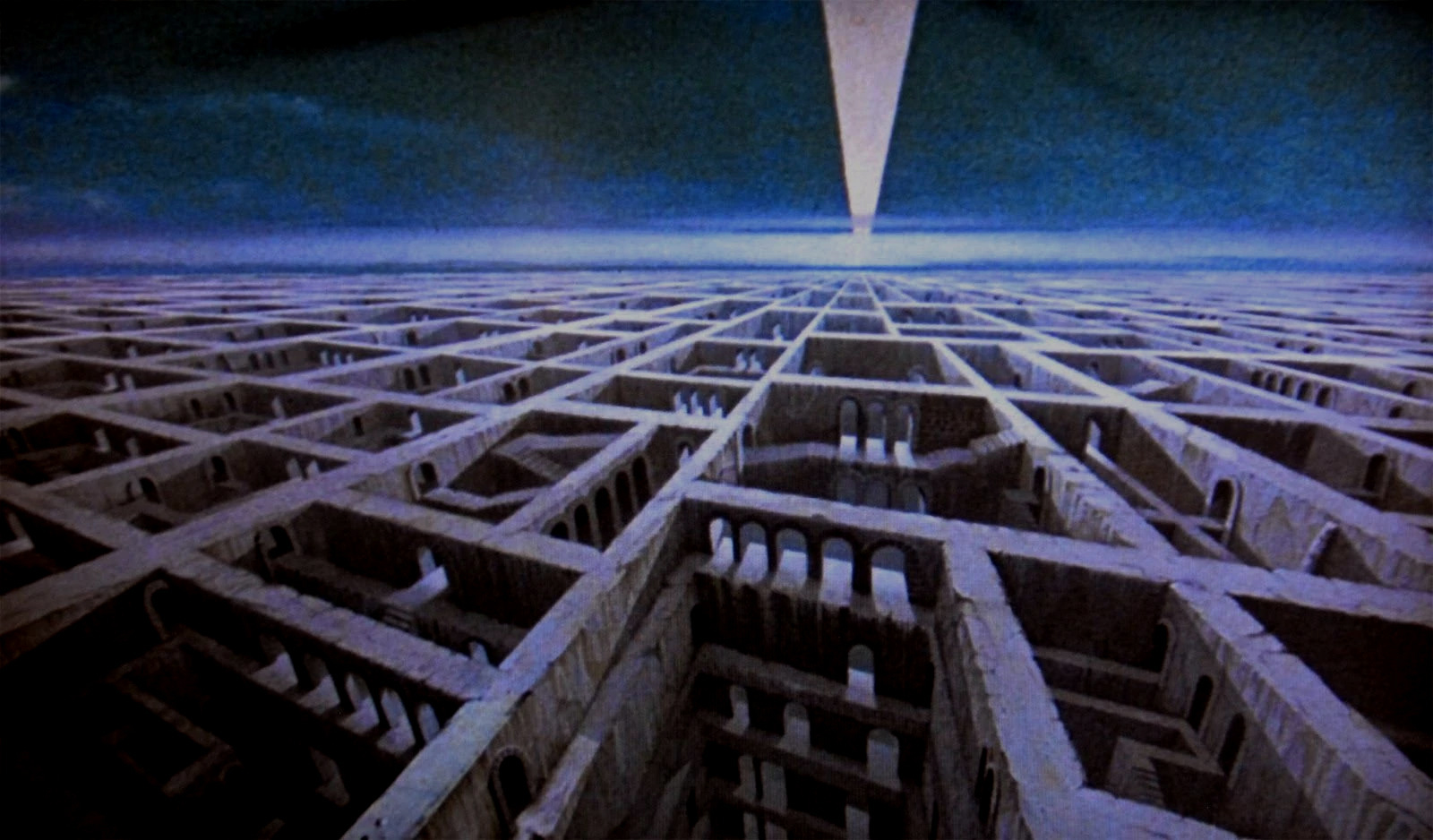

First and foremost, it means that objects are what they do. This necessarily implies that any given object – an automobile, a tree, a typhoon, an affect, a god, or a revolution – takes place over time. “Doing,” or activity – that is to say, producing a regime of effects in multiple registers at multiple scales – produces causal multiplication, or ripple effects. This causal rippling refers to a property that obtains in sequences of multiple effects such that each effect to some extent both conditions and is conditioned by all the other effects in each sequence. This causal rippling is fundamentally characteristic of objects, because objects do not – indeed, they cannot – exist as closed or isolated unities. Think of it like this: objects are more like knots than they are like beads. Hence, an object is an intersection, or a nexus, of various ontological strands. Objects always hook into objects always hook into objects, ad infinitum. This doesn’t that everything equivocates, nor that objects don’t “really” exist. There is nothing illusory about a knot. But the right ontological question is never “Does such-and-such an object exist?” but rather “How does such-and-such an object exist?” For too long, philosophers have viewed existence as a kind of compliment one gives to favored object types or else withdraws from disfavored objects, which are then cast into the outer darkness of nonexistence. But objects don’t just sit there passively, waiting for subjects to intervene. Instead, by hook or by crook, objects proceed along their own sinister pathways, often confounding or testing all dexterity. They have a howness; they exist in a certain way. Without this howness, inquiry into existence (of whatever mode or order, or by whatever method) would be an impossible and quixotic task. Philosophy would collapse into ethnos, and the sciences would just manifest bad old power politics.

This is not to suggest that subjects and objects either cannot or do not interact. Nor is it to propose noninterventionism as the preferred or prescribed stance of the subject toward the object world. Indeed, on this account, it becomes unclear what such a noninterventionist stance could even look like. There is no away from the world of objects. To the contrary, the subject (or, rather, subjectivity) is an emergent or functional property we impute to a determinable, identifiable class of objects. In other words, subjectivity is a vast and storied descriptive apparatus we attach to a set of peculiarly motile objects. In this regard, as in the descriptive apparatus attending the concept of the object itself that’s under revision here, the subject-object distinction defamiliarizes. Objects act, which makes them subjects (on the mistaken standard assumption anyway, see above), and subjects are objects, because preserving the distinction in question stops mattering in the same way if the dark lives of objects are released from their mute consignment to static inventories awaiting mobilization by the dexterous. Subjects lose nothing on this theoretical approach, but they do gain plethoras of object worlds to explore and to map and in which to act, with which to interact. Likewise, objects become sinister (from sinistral, referring to the left-hand side, contrasting with the dextral, or the right-hand side), which is to say that they traverse the causal strangeways in a manner much their own.

Excursus 3: “The Malice of Inanimate Objects”

The British author of ghost stories M. R. James begins his last published short story, “The Malice of Inanimate Objects” (1933), by observing that in everyone’s life, “there have been days, dreadful days, on which we have had to acknowledge with gloomy resignation that our world has turned against us.” He specifies that he is not referring to the human or social world, but, rather, to “the world of things that do not speak or work or hold congresses and conferences.” The story follows two gentlemen, Burton and Manners, who go for a walk after reading in the newspaper that George Wilkins, an acquaintance of both (and a fellow with whom Burton had recently disagreed most contentiously), has killed himself. On their walk, Burton, who has already cut himself shaving, nearly trips on a step and also loses his hat to a rogue branch. The two come across an abandoned kite: “a puff of wind raised the kite and it seemed to sit up on its end and look at them with two large round eyes painted red, and, below them, three large printed red letters. I.C.U.” Manners laughs. “‘Ingenious,’ he said, ‘it’s a bit off a poster, of course: I see! Full Particulars, the word was.’” After an unsettling encounter with a stuffed parrot in a shop window, as well as other small and sundry misfortunes afflicting Burton (“He choked at lunch, he broke a pipe, he tripped in the carpet, he dropped his book”), the two gentlemen part ways. Shortly thereafter, Burton dies most gruesomely: “apparently someone tried to shave Mr. Burton in the train, and did not succeed overly well.” For the nameless narrator, of course, the suggestion is that lurking behind the titular malice of inanimate objects is “something not inanimate,” but, rather, punitive and purposive. When everything bites, so to speak, perhaps it’s only misfortune, but it may well be reprisal for our “obliquities” or turpitude. But another interpretation haunts the story. However, James balks at the horizon of this second interpretation. He retreats from his own audacity by returning from the hinterlands of speculative possibility to the more familiar (and far less intriguing) highlands of moral certitude. On this second interpretation, there’s the far more disquieting assertion that, in fact, the objects themselves do exercise agency of a sort. Hence the ambiguity of the kite’s disturbing and fragmentary message. Is it just a ghostly telegram from the other side, Wilkins’ message to Burton that his enraged specter will not rest until it is revenged? Are the “full particulars” the details of their disagreement, or else Wilkins’ postmortem plans for Burton’s demise? Or do the “full particulars” refer to the realist particulars and discrete properties of that whole inhuman host of inanimate objects threatening to be far less inanimate than one might otherwise prefer to assume? On this view, the objects are always rustling. They trundle about in the world’s darkness. From the vantage point of the standard assumption about objects, this is the true reality of horror, then: I see you. Through strange red eyes, or through no eyes at all, the objects are looking back.

See “The left hand of all creation: how to repurpose whole worlds” or go forward to Part 2 (“Freeing up the objects for use”).