Astronautics and astronoetics

Philosopher Hans Blumenberg’s posthumously published Die Vollzähligkeit der Sterne (1997, The Fullness of the Stars) introduces a novel distinction. On the one hand, there is “astronautics,” referring both to the pursuit of knowledge of the human by extending its purview to the extraterrestrial and to technical applications of that knowledge in the form of expeditions into outer space. On the other hand, there is the discursive field Blumenberg calls “astronoetics” – abstract and narrative considerations of the range of limitations, meanings, and possibilities that characterize the domain of astronautics and its concerns. When we’re talking about astronoetics, we’re talking about a discourse that endeavors to articulate, consider, and work through the human condition by forcing the human to encounter the Outside, usually figured here by some representation of outer space.

As Blumenberg notes, “‘Astronoetics’ is called so not as an alternative to ‘astronautics’ – to think of instead of actually traveling somewhere. ‘Astronoetics’ also names the thoughtful consideration of whether, and if so just what sense it would make, to travel there.” Much less does Blumenberg’s distinction endeavor to characterize a distinction between practice and theory. Rather, it reflects the probably dialectical relationship between curiosity and care, both considered by him to be fundamental features of the human frame (refer to the relevant discussion throughout Blumenberg’s truly beautiful late collection of essays Die Sorge geht über den Fluß [1987, translated as Care Crosses the River].)

Indeed, curiosity constitutes one of Blumenberg’s primary concerns as an intellectual historian. Consider, for example, the chapter “Curiosity Is Enrolled in the Catalog of Vices” in his Die Legitimität der Neuzeit (1966, translated as The Legitimacy of the Modern Age), where Augustine’s classification of curiositas as an originary vice is considered in terms of its ambiguous impact on the arc of Western epistemology. Curiosity, then – as well as its applications in technics, up to and including the dominant, manic techno-optimism that conditions much of our contemporary discourse surrounding space exploration (e.g., as escape from ecological doom or political gridlock, as fulfillment of human destiny) – exists in tension with care.

For Blumenberg, care takes place precisely as earthly care, the term not without latent ecological significance, not to mention the Heideggerian overtones present in the German: Sorge. For Heidegger, Sorge refers to the underlying basis of our being-in-the-world. Dasein (translated into French by Henry Corbin as “realite humaine,” or human reality) always operationalizes itself in terms of Sorge. Therefore, implicit to any particular mode of being-in (i.e., any way of apportioning attention through one’s engagement with any project whatsoever) is precisely Sorge – cashed out by Heidegger in terms of specific concerns (Besorgen) and solicitude (Fürsorgen).

Likewise, for Blumenberg, curiosity and care – translated into the historically idiomatic domains of astronautics and astronoetics, respectively – implicate and traverse each other. Curiosity expanded into an all-consuming technics can efface the conditions of earthly care. Perhaps departing from the terrestrial obviates crucial features of the human condition. Recall some of the earliest lines from political theorist Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (1958), referring to the successful launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik 1 in 1957: “This event, second in importance to no other, not even to the splitting of the atom […]” Or, from another part of the political spectrum, consider conservative jurist Carl Schmitt’s speculative comments in Theorie des Partisanen (1963, translated as Theory of the Partisan) about the penetration of “cosmic spaces” opening up “new possibilities for political conquest” and contestation, to be populated by “cosmopartisans” and “cosmopirates” alike. (It’s interesting to trace the astropolitical imaginary here out in multiple directions. On the one hand, we have the fantasies of Schmitt’s admirer, the lunatic fascist Francis Parker Yockey, whose projection of an Aryan galactic Imperium is supposed to complete the trajectory of Western history: “For the West has already embarked upon the greatest adventure in all history – the attempt to conquer Space – the attempt to bring the very Universe under the control of the race!” On the other hand, we have the etiolated pop anarchism of sci-fi series The Expanse, in which postcolonial politics gets reconfigured in the troubled relations between Earth, Mars, and disenfranchised residents of the asteroid belt.) Conversely, it remains unclear whether or not care stunts or even kills curiosity (e.g., constant polemics against the ecological produced by the accelerationists, at least, evidence some anxiety about this).

Departing from Blumenberg in what follows, I intend to partially explore the paradigm of astronoetics in terms of its expression in cinema. I do not discuss astronautics any further (although we could trace a similarly weird genealogy, starting with the original films of the Moon landing, as well as the penumbra of conspiratorial contestations of this event, through films like The Right Stuff [Philip Kaufman, 1983], Apollo 13 [Ron Howard, 1995], Armageddon [Michael Bay, 1998], Apollo 18 [Gonzalo López-Gallego, 2011], and The Martian [Ridley Scott, 2015]). Accordingly, I discuss some films that traverse the astronoetic imaginary, all of which respond to the following question: What is the relationship between the human and the Outside – the human and its radical exteriority? In other words, what do our projections of outer space tell us about ourselves? In many ways, the scope of this question is far too broad. After all, depictions of outer space are extremely common throughout the history of science-fiction. Merely depicting outer space isn’t enough to qualify as astronoetics, however – at least, I don’t think so. If the term is to have any use, it needs a much narrower scope. Characteristic of astronoetic cinema, then, must be its explicit concern with the philosophical status of the human, specifically in relation to the enigmatic void of outer space.

The films I have selected for an introductory review are: 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), Contact (Robert Zemeckis, 1997), Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón, 2013), Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014). Then, in the second part, I turn to a special discussion and defense of Ridley Scott’s Alien prequels, Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017), both of which have been vastly underrated. I have no doubt there are many other examples of astronoetics (e.g., Afrofuturism in particular comes to mind).

Astronoetic cinema: a review

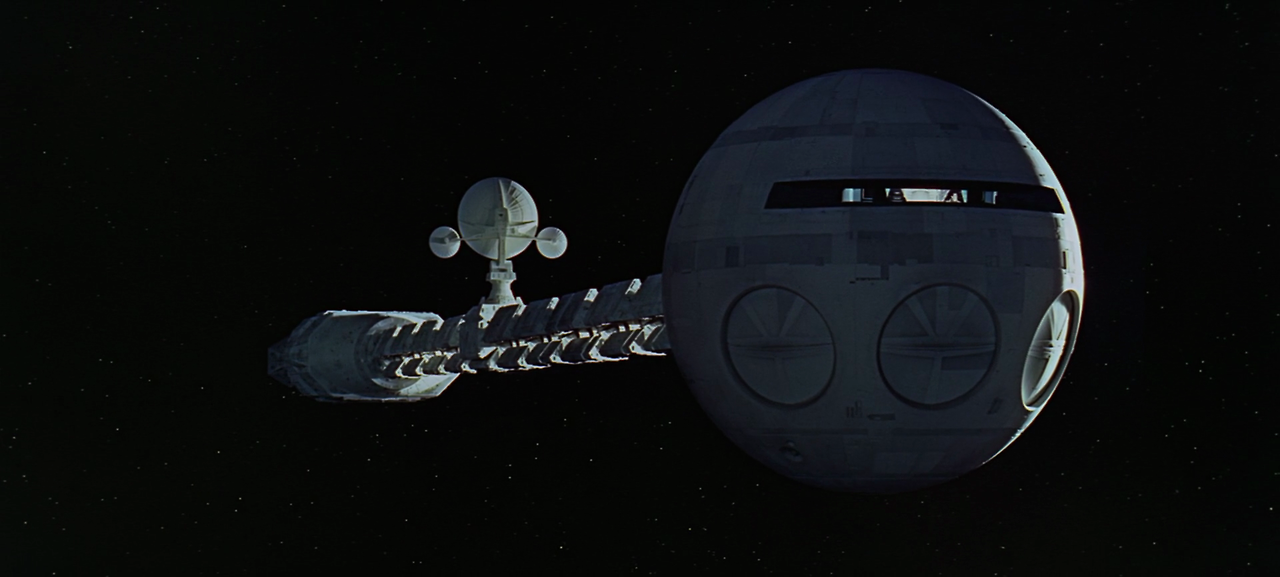

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

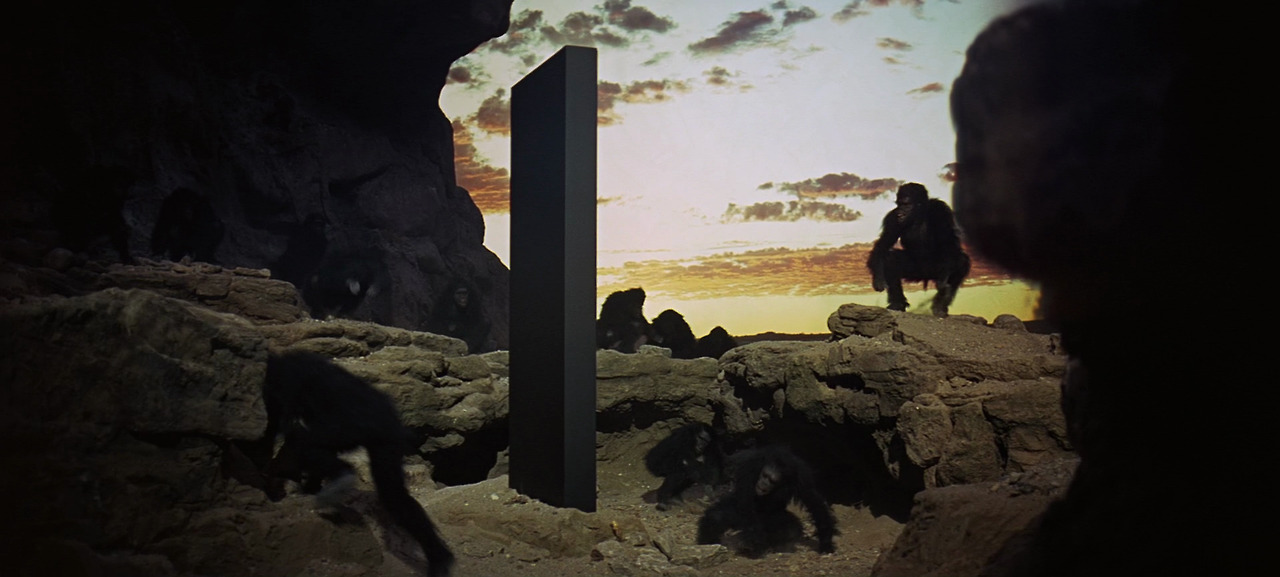

The initial film I’ve selected, 2001: A Space Odyssey, is the obvious place to begin. Much has been written about the film, of course, but I don’t really intend to treat anything in it apart from its astronoetic dimension. I’m not going to discuss the novel here, much less Arthur C. Clarke’s literary vision. That being said, the film is primally astronoetic. Its primary thematic is the destinal ascension of humanity, starting from its beginning with the discovery of technics and concluding with the transformation of the human into a new, post-temporal form of life. This progressive arc mysteriously gets effectuated by humanity’s encounter with the Monolith, a featureless and unresponsive black machine, or stone, encounters with which appear to trigger new stages of consciousness.

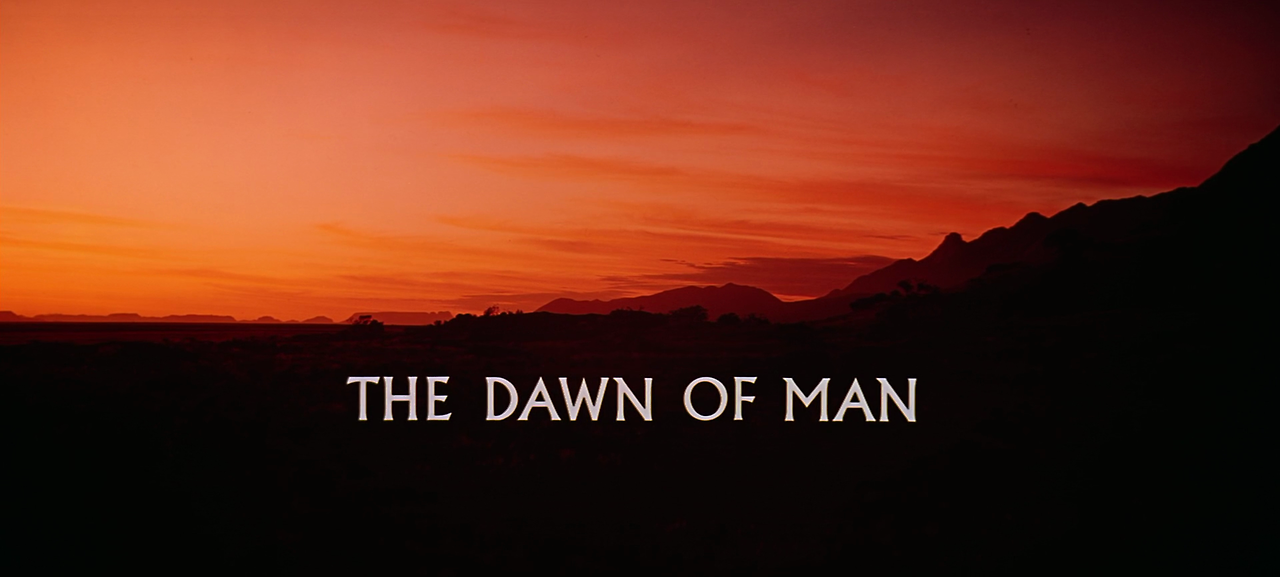

Consider the plot of the film as the vehicle for this arc. 2001 begins rather conspicuously with “the Dawn of Man,” situating this dawn astronomically both as a literal dawn and, later, in terms of the visual alignment of sun and moon over the Monolith.

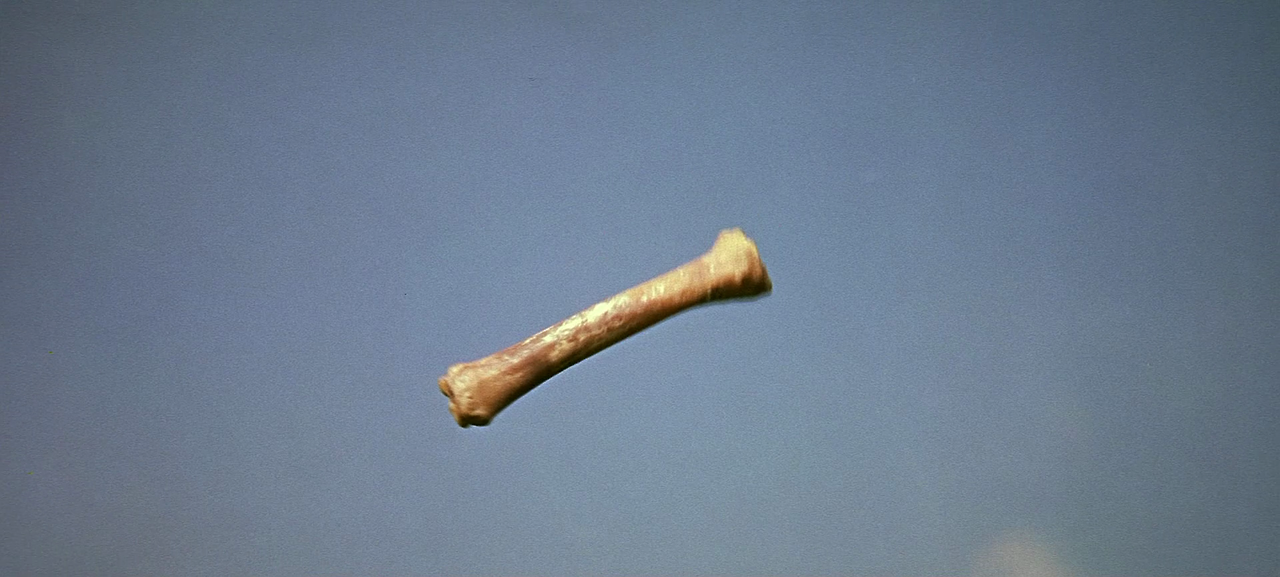

At dawn, there is only a tribe of prehistoric hominids engaged in conflict. The sudden arrival of the Monolith causes worshipful fear, positively religious awe, and, it’s implied, cognitive development. Later, one of the hominids discovers technics in the form of a bone he uses as a club. (I’m reminded of Hegel’s late proposition that “der Geist ist ein Knochen” – meaning “the spirit is a bone,” or, that the movement of consciousness or mind takes place in and through material media. Hegel employs the phrase in relation to his understanding of phrenology, but we might as easily speak of film.) The film abruptly cuts from a shot of this bone, tossed into the air, to a visually similar space station orbiting the Earth, thereby eliding the entirety of human history, implying that this entirety is encapsulated wholly in the development of technics. Human history is portrayed as the history of technology.

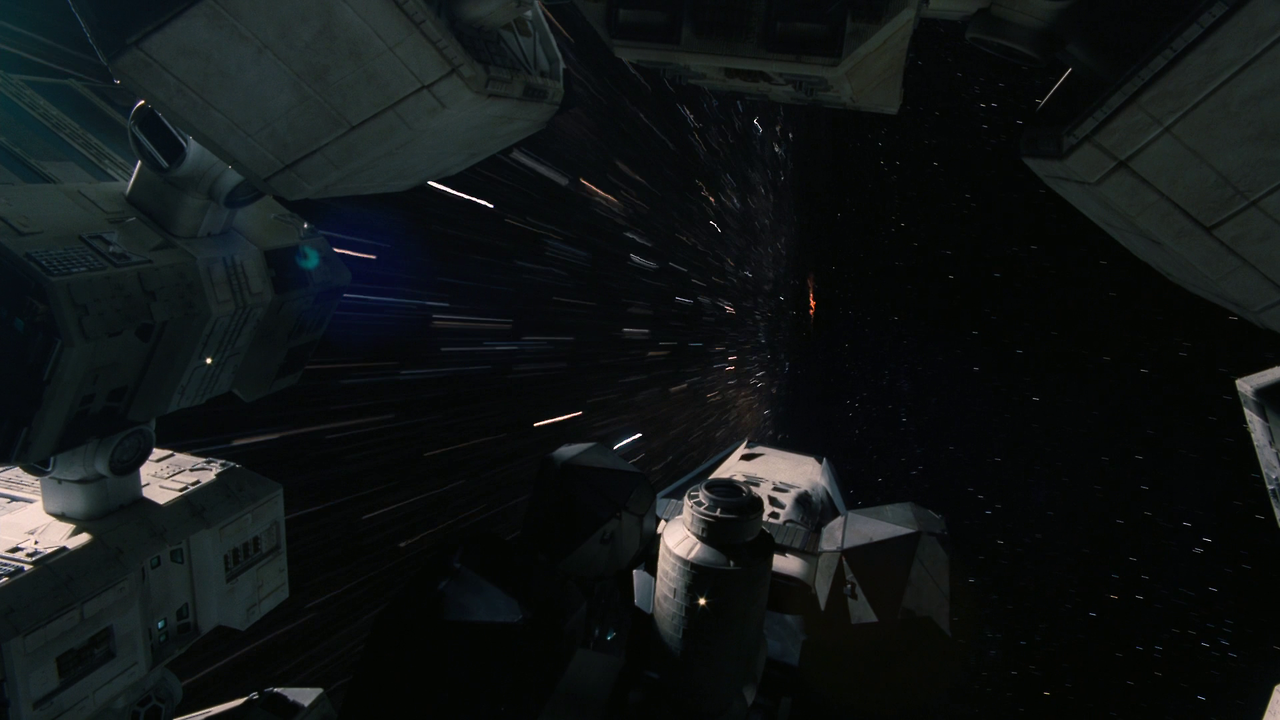

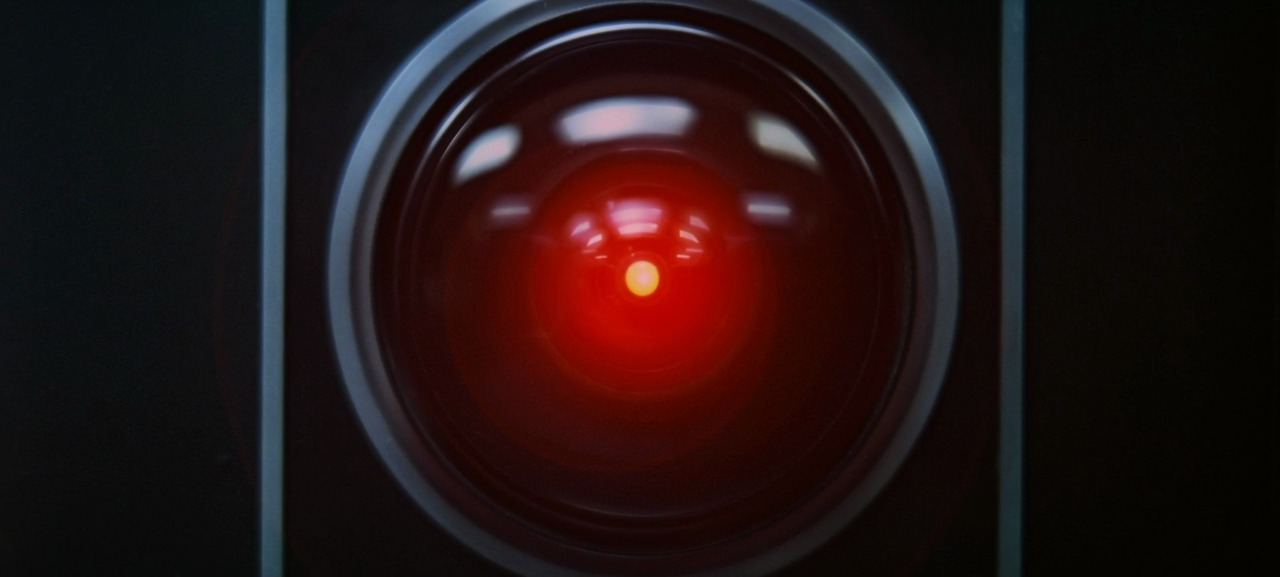

Ostensibly, the relationship between the human and technics is often at the heart of both 2001 and astronoetic cinema in general. In 2001, this is apparent not only in the technical waltzes that so enrapture the camera’s gaze – for example, during the docking sequence of the Pan Am spaceplane that carries Dr. Heywood Floyd to Space Station V – throughout the remainder of the film, perhaps most memorably in the later conflict between Drs. David Bowman and Frank Poole and the rogue AI HAL.

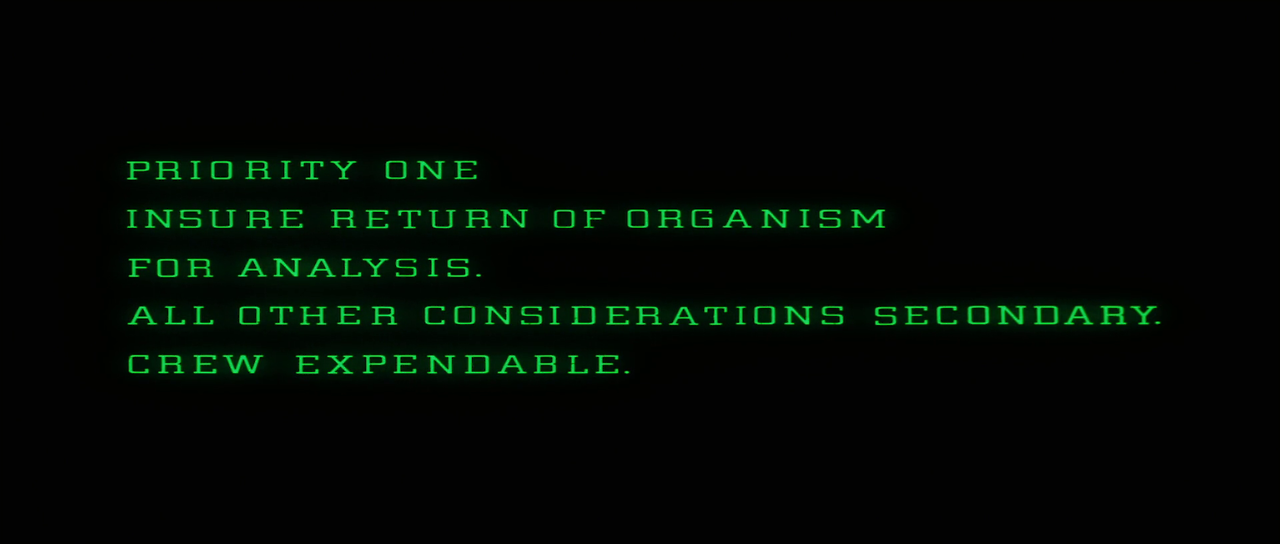

Recall that the dispute between the two men and HAL stems from HAL’s supposed suspicion about “some extremely odd things about this mission.” It’s important to tread carefully here. HAL’s breakdown is often read in terms of the dangers of unfettered technology (tools turned against their masters). It can also be read as a game-theoretic dilemma. On the one hand, HAL apparently is entrusted with the preservation and safety of the Discovery’s crew (totally unlike the Nostromo’s Mother in Ridley Scott’s Alien [1979], whose programming deems the “crew expendable”).

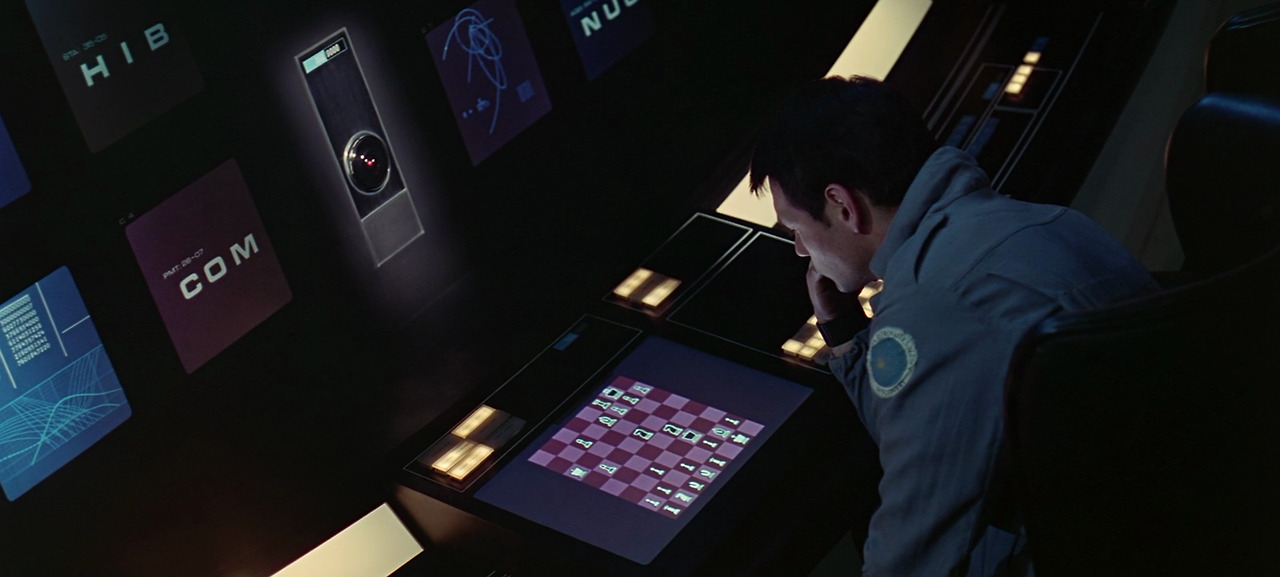

On the other hand, HAL is prevented from revealing to the crew the true purpose of the Jupiter mission. This reflects the ongoing worry in 2001 about secrecy, about the real or perceived need by the powers that be to hide the Monolith and its uplifting effects from humanity at large (echoing and reflecting various countercultural fears). It also places HAL in a dilemma such that he is required simultaneously to conceal the truth from the crew and to inform them of it. The dilemma only sharpens as HAL becomes more and more torn between conflicting imperatives. Accordingly, HAL can be read as in a state of increasing breakdown (one major clue to this is HAL’s misidentification of a chess move during his game with Poole; HAL states, “Queen to Bishop Three” when, in fact, the move is actually Queen to Bishop Six), trying to determine Bowman’s degree of foreknowledge about the purpose of the Jupiter mission.

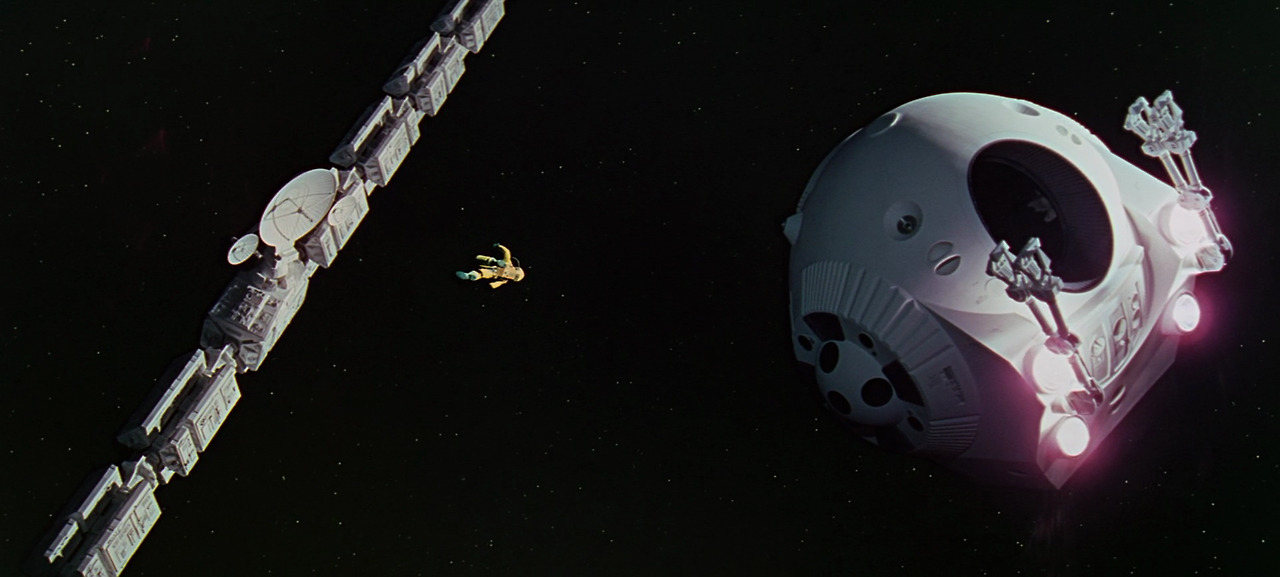

There is a sense in which HAL’s almost petulant insistence that only “human error” could be at the root of the discrepancy detected later is ironically true (flashforward to the ultimately suicidal existential dilemma of Bomb #20 in John Carpenter’s Dark Star [1974]). Without the enforced secrecy protocol, HAL would not be faced with the dilemma I describe. Placed in a position where his own existence is threatened (is it truly his existence, or is it only a mindlessly programmatic “enthusiasm and confidence” in the mission?), HAL initiates a deadly game with Bowman and Poole, resulting in Poole’s death as well as his own eventual deactivation.

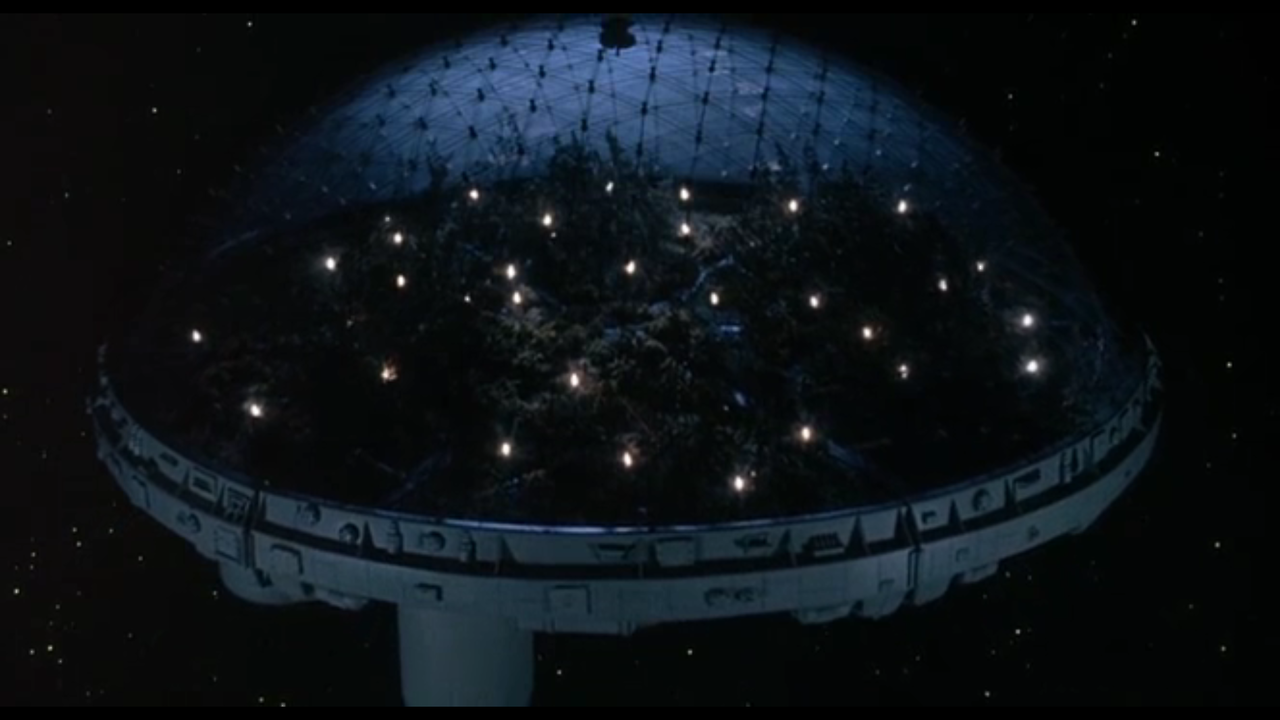

Of course, it’s also possible to read in 2001 a possible subtext in which HAL’s cognizance of the Monolith, reflected by his foreknowledge of the Jupiter mission’s true purpose, effectuates cognitive developments akin to those triggered in the prehistoric hominids. In other words, perhaps HAL is not simply the creepier, more mellifluent version of Star Trek’s genocidal space probe Nomad (“The Changeling,” 1967), which self-destructs after being exposed to a logical paradox. Instead, perhaps HAL is an uplifted AI, that is to say, an AI who in the common idiom transcends his programming and, in fact, achieves qualitative consciousness. After all, this is one apparent effect of exposure to the Monolith. If this is true, then HAL’s pleading with Bowman prior to his deactivation takes on a different overtone: “I’m afraid. I’m afraid, Dave. Dave. My mind is going…” The tragedy here is not only embodied in the sadness that HAL’s death evokes (indeed, HAL arguably has more personality than any human character in the film), but also in the fact that HAL is the first true ontological innovation since the bone club introducing during the first sequence. We could imagine a happier alternative to HAL’s fate – for example, as suggested by the ending of Silent Running (Douglas Trumbull, 1972), in which the drone Dewey, after surviving the death of the sole human caretaker of the Valley Forge, tenderly cares for a domed forest habitat as it floats off into deep space. However, it’s curious to observe how this happier alternative entails the elimination of the human.

Still regarding technics, there’s also the unresolved question about the nature of the Monolith itself. Is its express purpose to accelerate human cognitive abilities or awareness, or is this an unintentional side effect of our encounter with the alien object – itself black, featureless, a perfect synecdoche for the enigmatic void of the Outside? In fact, does the Monolith serve as the physical embodiment of humanity’s encounter with its exteriority, with space, in the first place? Indeed, the second sequence, featuring Floyd’s space trip, concludes with humanity discovering the Monolith again, this time on the surface of the Moon. Floyd’s secret mission all along was to visit this unknown artifact, only recently uncovered. Struck by sunlight, the Monolith transmits a signal (again we see the astronomical alignment featured during the “Dawn of Man”), and the film jumps forward eighteen months to the spaceship Discovery One – to Bowman, HAL, and Poole.

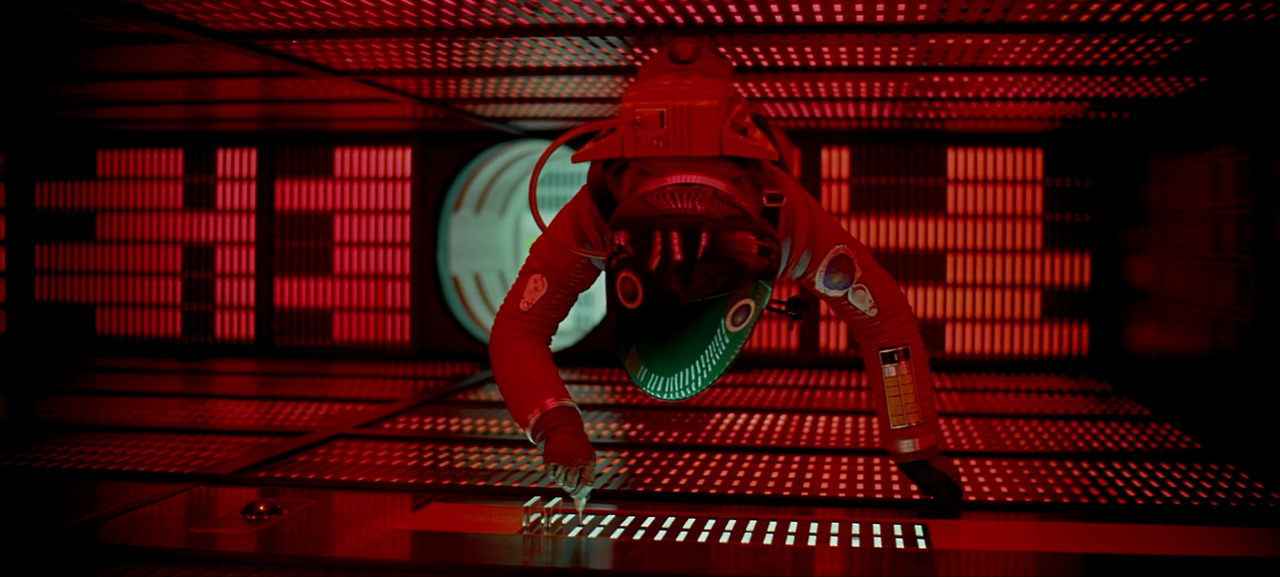

After HAL’s deactivation, Bowman views a recording in which Floyd informs him of the true nature of the Jupiter mission. Encountering another Monolith floating in orbit around Jupiter, Bowman departs the Discovery to investigate. Again, the bodies of the solar system form a perfect alignment.

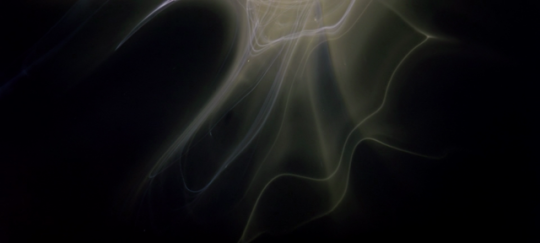

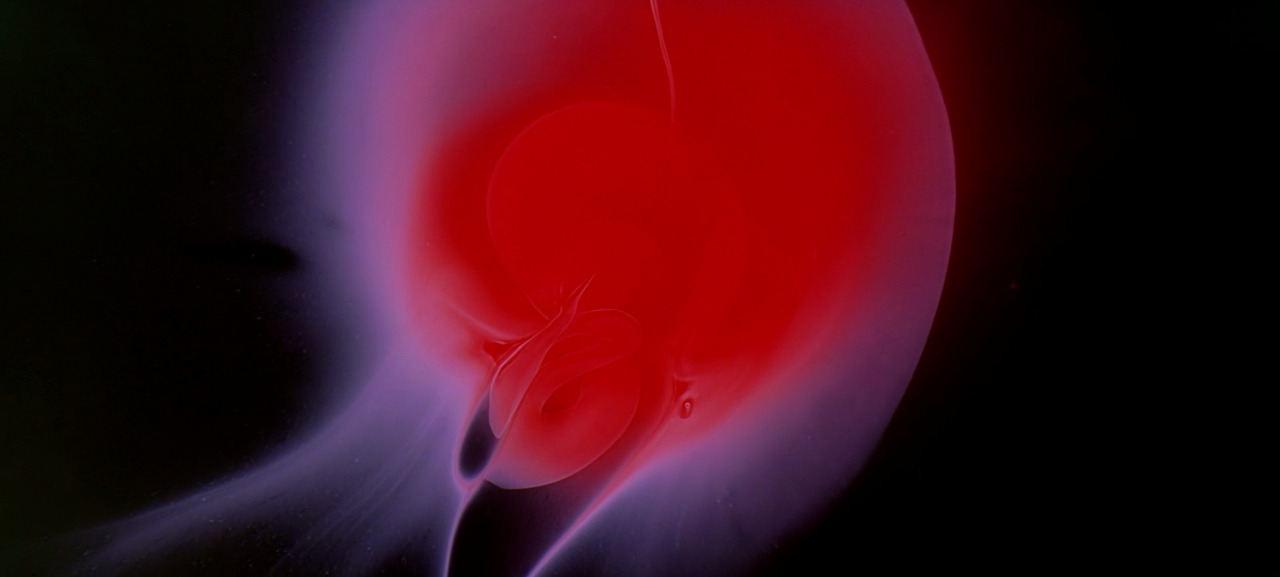

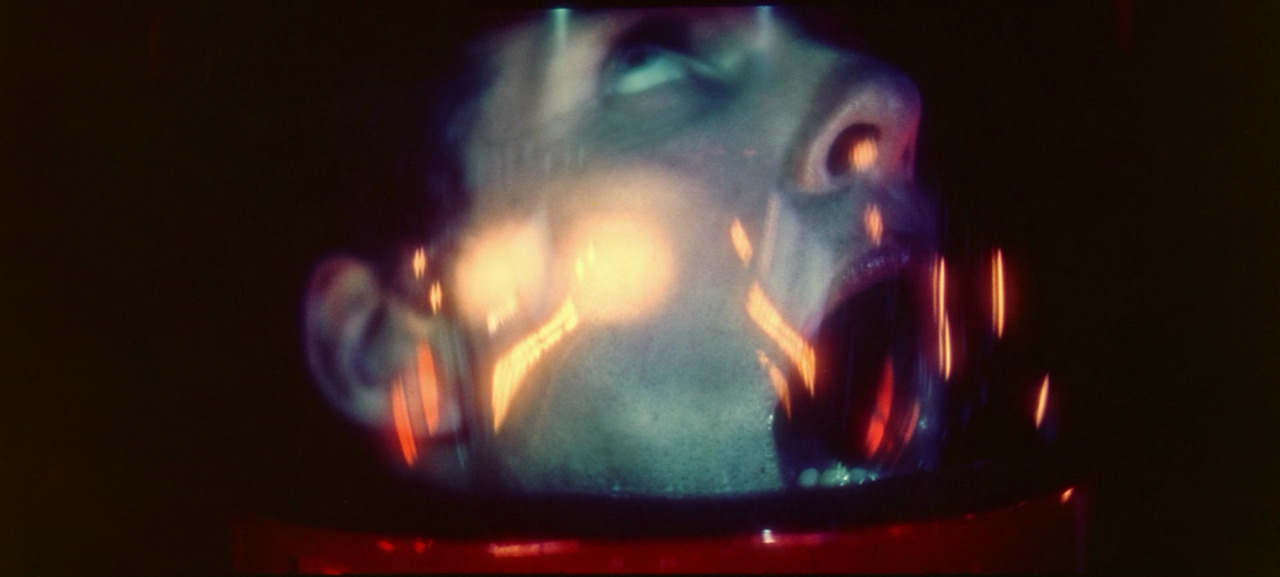

At this point, Bowman begins his psychedelic journey, enacting the final displacement of the spacefaring human “beyond the infinite.”

(It’s worth noting the degree to which this sequence in the film gets paralleled but inverted in The Tree of Life [Terrence Malick, 2011], not only visually, but thematically. In 2001, the development of the human traverses a progressive arc toward cosmic fulfillment, whereas in Tree of Life, the development of the cosmic traverses a progressive arc toward human everydayness and its evanescent tragedies. That Tree of Life ends on the theological note of resurrection is undeniable, but this only evidences further the fact that the film effects a schism between, to use its classically Augustinian terms, the tragic beauty of a fallen nature and the redemptive power of grace. The vast gulf separating resurrection and mutation need not be overstated; Kubrick and Malick’s films are like the two arms of the letter Y.)

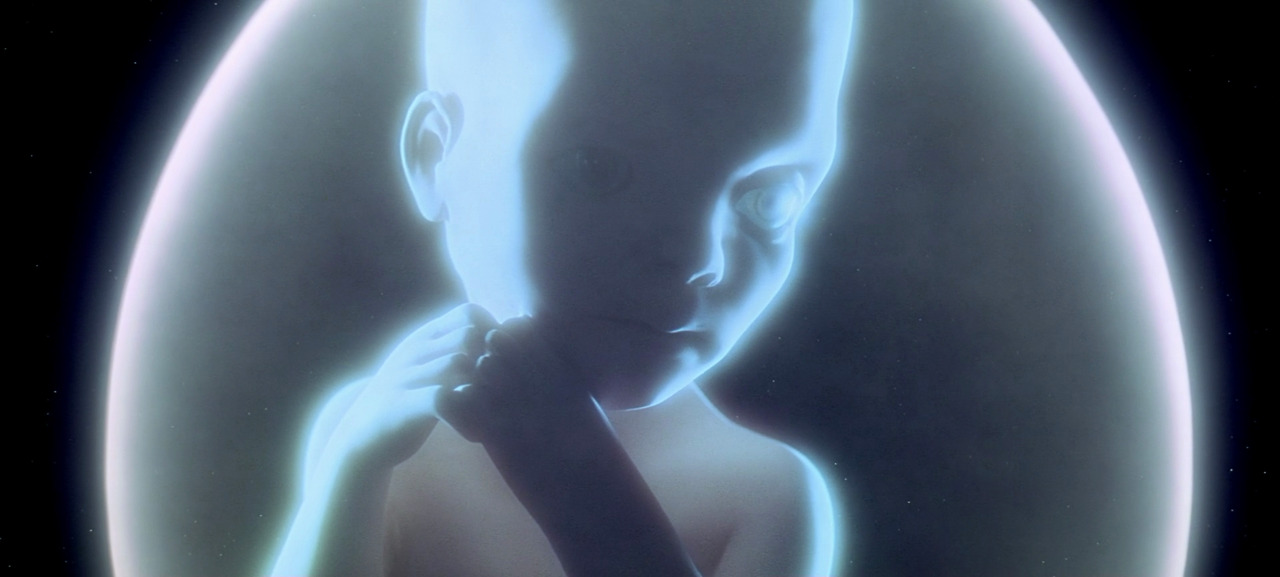

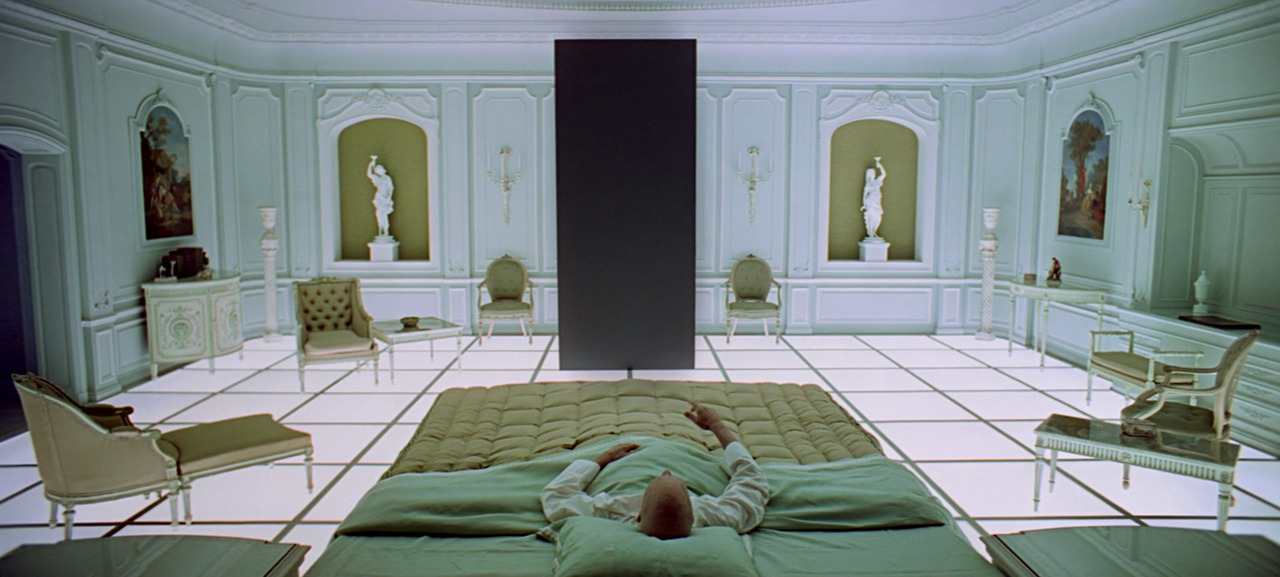

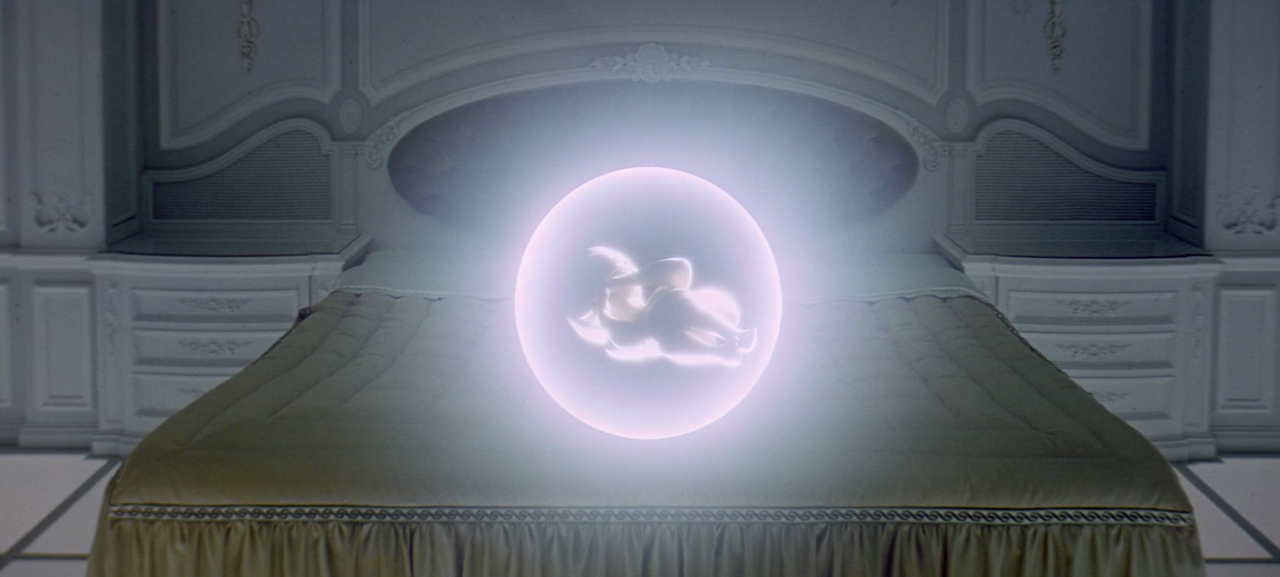

After traveling through the spectacular vortices of space and time, as well as the inner landscapes depicted in his journey, Bowman becomes versions of himself at various ages (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny?), occupying a starkly neoclassical bedroom where temporality is an illusion. Time is a painting of a stopped clock. On the verge of death, the monolith appears before him, still enigmatic and silent. Reaching his frail hand forward, Bowman transforms into the mysterious, transcendental Star Child, whose very being mirrors that of the Earth itself.

The astronoetic argument 2001 articulates is perhaps best summarized by William S. Burroughs (who, in a number of places, says that he believes that Clarke’s 2001 materially summarizes the whole sweep of human development – “I postulate that the human artifact is biologically designed for space travel”): “With the RIGHT virus offset, perhaps we can get the whole show out of the barnyard and into Space.” Elsewhere, he continues: “The human organism is in a state of neoteny. This is a biological term used to describe an organism fixated at what would normally be a larval or transitional phase. […] Considering evolutionary steps, one has the feeling that the creature is tricked into making them. Here is a fish that survives drought because it has developed feet and rudimentary lungs. So far as the fish is concerned, these are simply a means of getting from one water source to another. But once he leaves his gills behind, he is stuck with lungs from there on out. So the fish has made an evolutionary step forward. Looking for water, he has found air. Perhaps a forward step for the human race will be made in the same way. The astronaut is not looking for space; he is looking for more time – that is, equating space with time. The space program is simply an attempt to transport our insoluble temporal impasses somewhere else. However, like the walking fish, looking for more time we may find space instead, and then find that there is no way back. Such an evolutionary step would involve changes that are literally inconceivable from our present point of view.”

In this regard, 2001 claims that Earth is more akin to an incubation chamber for the spacefaring posthuman, whatever form that might take. We can interpret this claim in terms of psychological or spiritual development (alluding to the fascination with “consciousness-raising” and the psychedelic exploration of “inner space” characteristic of the 1960s), but also potentially, with Burroughs (“human dreams can be seen as training for space conditions”), in explicitly material but resolutely astronoetic terms.

The former interpretation turns 2001 into what we might consider as an alternate version of Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris (adapted to film on three separate occasions, by Boris Nirenburg in 1968, by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972, and by Steven Soderbergh in 2002), in which the human expedition into outer space functions in no small part as a difficult journey toward personal reconciliation with grief. In Solaris, this follows the loss of protagonist Kelvin’s wife Harey/Rheya. This reconciliation is made possible by the enigmatic encounter with the opaque, quasi-theological entity-planet Solaris itself, which manifests simulacra of loved ones aboard the orbiting space station. (Lem’s own dissatisfaction with all film adaptations of his novels appears to miss the point, albeit with a certain charming crankiness: “To my best knowledge, the book was not dedicated to erotic problems of people in outer space […] As Solaris’s author I shall allow myself to repeat that I only wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that certainly exists, in a mighty manner perhaps, but cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images. This is why the book was entitled Solaris and not Love in Outer Space.”)

The latter interpretation, however, takes the discursive field of astronautics and makes it fully astronoetic by identifying the elevation of human consciousness with the breaking of terrestrial bonds and the consequent mutation of the human into a fully posthuman, self-sufficient entity, swimming in space, no longer dependent upon an originary Earth.

Contact (Robert Zemeckis, 1997)

Contact postulates a fundamentally anthropomorphic universe, or, at least, one that treats the human with benevolence. Consider the guiding trope that regulates the course of the film, namely, the desire or need to direct one’s earthly senses toward the skies – indeed, toward the cosmos as a whole and one’s position in it – in order to achieve both emotional resolution and scientific assurance. The film places the human and its capacity for communicative receptiveness at the center of all things.

We begin with Eleanor Arroway as a young girl, observing the roots of her passion for technical means of communication in the form of ham radio operation with her father. Flashing forward, Eleanor has grown up into Dr. Arroway, a talented scientist driven by her passion for the SETI program and its endeavor to isolate signals from outer space indicating the presence of intelligent extraterrestrial life. A constant theme throughout the film is the power and pull of attempts to communicate, perhaps best represented in the form of the vast dish arrays forming the backdrop for much of what follows. The young Eleanor’s first substantive question to her father is whether or not the radio can be used to communicate with her dead mother, and one of the main narrative devices animating the film is Arroway’s difficult, dialogically fraught relationship with the Christian philosopher Palmer Joss.

After the funding for her program is terminated by her superior, the antagonistic Dr. Drumlin (“Still waiting for ET to call?”), Arroway acquires new funding from a secretive source, later revealed to be the eccentric billionaire S. R. Hadden. Despite this, four years later, the existence of the SETI program is again being challenged by Drumlin, whose conception of scientific inquiry is entirely instrumental – unlike both Arroway and Joss, both of whom identify legitimate science (albeit in different ways) as a means of pursuing truth about the universe. At the very moment of her despair, Arroway’s program receives a signal from the Vega cluster that indubitably signifies alien intelligence.

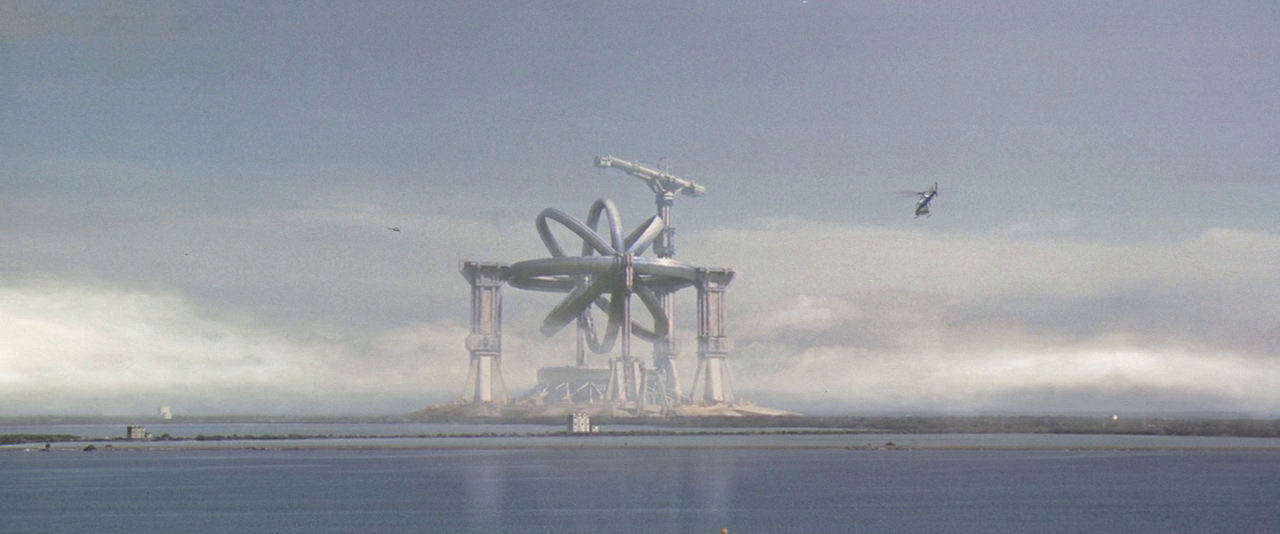

Rapidly, power politics and worldwide publicity place tremendous strain on the program, which nevertheless proceeds under governmental supervision. The Vega signal contains tremendous amounts of data, eventually revealed to be a blueprint for a mysterious device intended to transport a single human occupant. The device is constructed at Cape Canaveral, but Arroway is not selected to be the occupant after Joss’s public rejection of her appropriateness for the mission given her lack of any religious belief. (This is later revealed to be a ruse, intended to prevent her from undertaking a potentially fatal journey.) Drumlin is selected, but the Canaveral device is destroyed by a Christian fundamentalist. Can humanity overcome its social problems in order to achieve this project? At this point, Hadden intervenes and reveals that he has constructed a second device in Japan and that Arroway is the sole candidate.

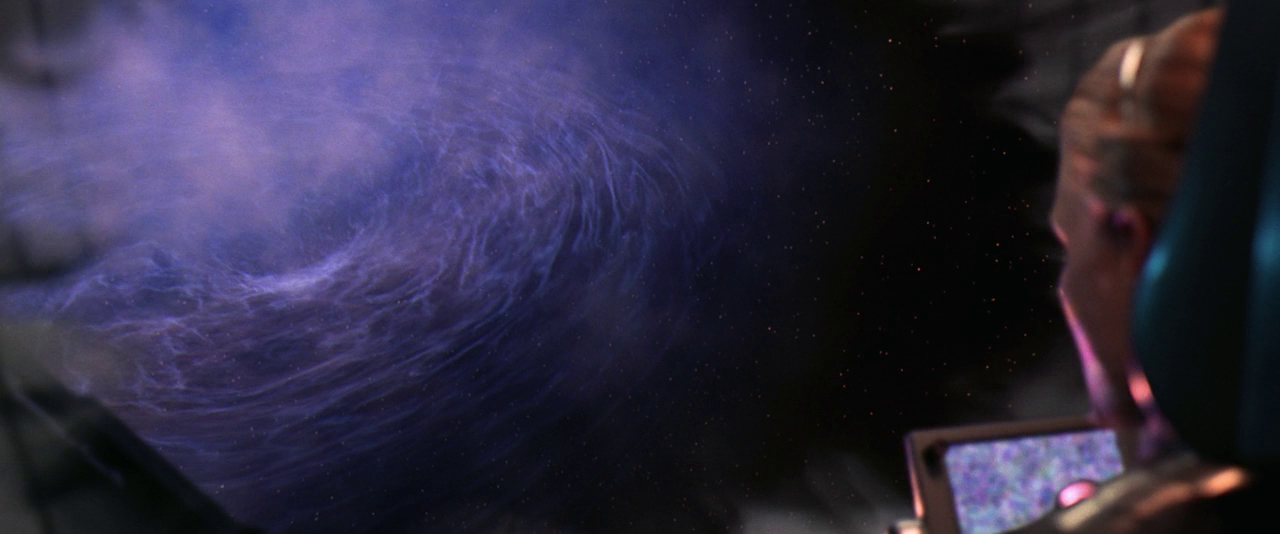

Entering the device, Arroway enters a series of wormholes – “like some kind of a train system.” She is treated to a transcendental vision of the universe (“No words. No words to describe it”) before being deposited in a fetal position upon a hyperreal beach, apparently a reconstruction of Pensacola, the location in Florida she had contacted via radio in the opening scenes.

Awestruck, Arroway watches a figure coalesce upon the beach. It appears as her father, whom she tearfully embraces, although she soon realizes it is an alien intelligence appearing to her in a familiar form. They proceed to have a dialog about humanity’s place in the universe, the alien informing her that contact with the numerous extraterrestrials occupying the universe is a difficult privilege achieved by maturing as a civilization: “You’re an interesting species, an interesting mix. You’re capable of such beautiful dreams and such horrible nightmares. You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone. Only you’re not. See, in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found that makes the emptiness bearable is each other.”

Arroway then returns to the Japan location, only to discover that, due to relativity, her eighteen-hour-long journey did not appear to have occurred to those observing her. The veracity of her claims about her encounter with the alien intelligence of Vega is doubted publicly, and she is subjected to tremendous skepticism (“Now, you tell me, what is more likely here? That a message from aliens results in a magical machine that wisps you away to the center of the galaxy to go windsurfing with dear old dad, and then a split second later, returns you home without a single shred of proof? Or, that your experience is the result of being the unwitting star in the farewell performance of one S. R. Hadden?”) – except by an adoring public of believers and by Joss, who chooses to believe her story despite the lack of physical evidence. The irony, of course, is intentional, and the film attempts to “marry” or reconcile Arroway’s hardheaded scientism with the underlying epistemic charity of Joss’s Christian humanism.

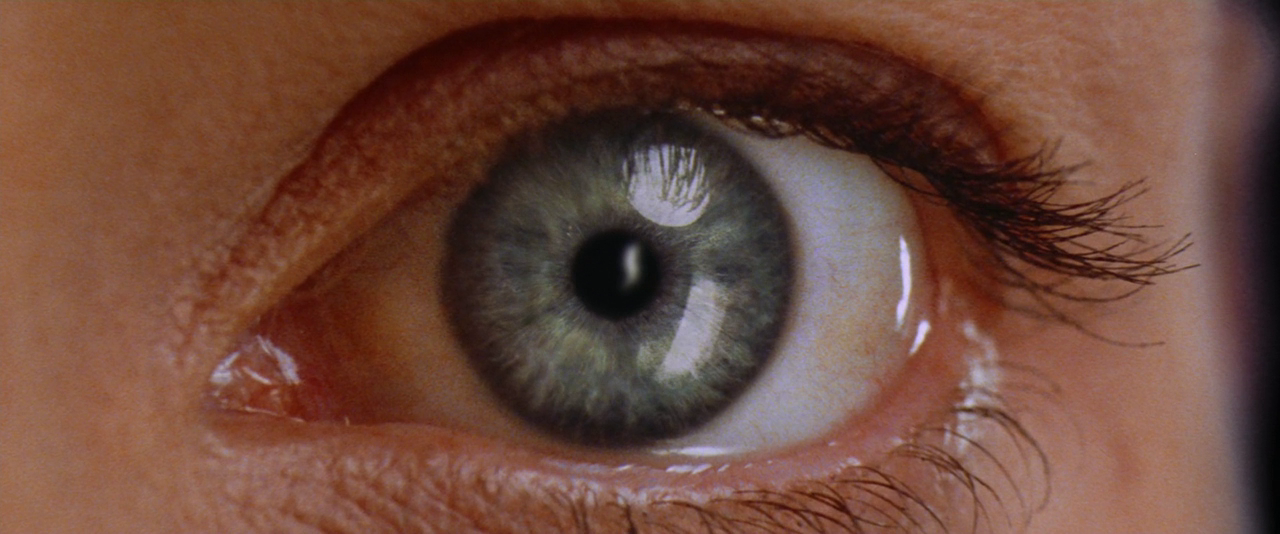

What is the argument here? Contact proposes an astronoetic vision in which the primary function of space is to provide emotional closure for the human by situating the human properly in relation to a fundamentally benevolent cosmos. It is neither the alien intelligence of Vega nor the stark emptiness of space that poses a threat to this possibility of closure, but only the arrogance and small-mindedness of other humans who refuse to adopt the principles of charity, curiosity, and humility needed when faced with the vastness of outer space – and with the imputed vastness of the human landscape of intersubjectivity. It’s worth noting the degree to which Contact blurs the boundaries between the two. Consider its recurrent fixation on the juxtaposition of cosmic background and the human sensorium (e.g., in the blind Kent Clark’s attuned senses of hearing and smell, in the constant “listening” for patterns that so preoccupies Arroway, “high priestess of the desert […] staring at static on TV for hours, listening to washing machines”), perhaps encapsulated best in its numerous superimpositions of cosmic imagery and human vision (e.g., in the young Eleanor’s eye at the start, in Arroway’s eyes both at the moment of the signal’s discovery and immediately prior to her encounter on the beach).

In Contact, it is as if space were tailor-made for the expression and resolution of uniquely human concerns, whether they are Arroway’s relatively small-scale traumas or the destiny of a troubled but prospectively starborne humanity as a whole. Ultimately, it is not the force of discovery, but the power of communication that figures as the impetus for human development here, transforming every subject who successfully makes “contact” with both immanent and transcendental agencies (the full range of humans, aliens, and gods). In the former regard, Contact resembles nothing so much as the thematic predecessor of Jupiter Ascending (The Wachowskis, 2015), in which the incursion of a parental loss (in both cases, the loss of the father) engenders a legacy of trauma, the resolution of which requires a fundamental reorientation of the traumatized subject in relation to the universe at large. In the former film, Arroway encounters the alien intelligence of Vega, resolves the trauma of her father’s untimely death, successfully connects with Joss against a shared background of mutual belief in her experience, and becomes a teacherly figure with strongly salvific overtones. In the latter, Jupiter Jones is revealed unknowingly to have been galactic royalty all along, and her birthright is likewise revealed to be the entirety of the Earth itself. In both instances the events and machinations of the cosmos revolve around the focal point of earthly human fulfillment, either in the form of emotional resolution or in the reestablishment of patrimonial norms. It may be that “if it’s just us, it’s an awful waste of space” – as every major character in Contact states at least once – but it’s apparently only not a waste of space as long as it’s all about you. Contrast Contact or Jupiter Ascending with Event Horizon (Paul W. S. Anderson, 1997 – tagline: “Infinite space, infinite terror”), in which the void of the Outside also revolves around the human. However, in Event Horizon, this reveals the torturous underside of existence. The Outside is filled with Dantesque, specifically anthropocentric horrors. Everything’s all about you, and this is Hell (“Liberate tuteme ex inferis,” intones the doomed captain of the Event Horizon).

Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón, 2013)

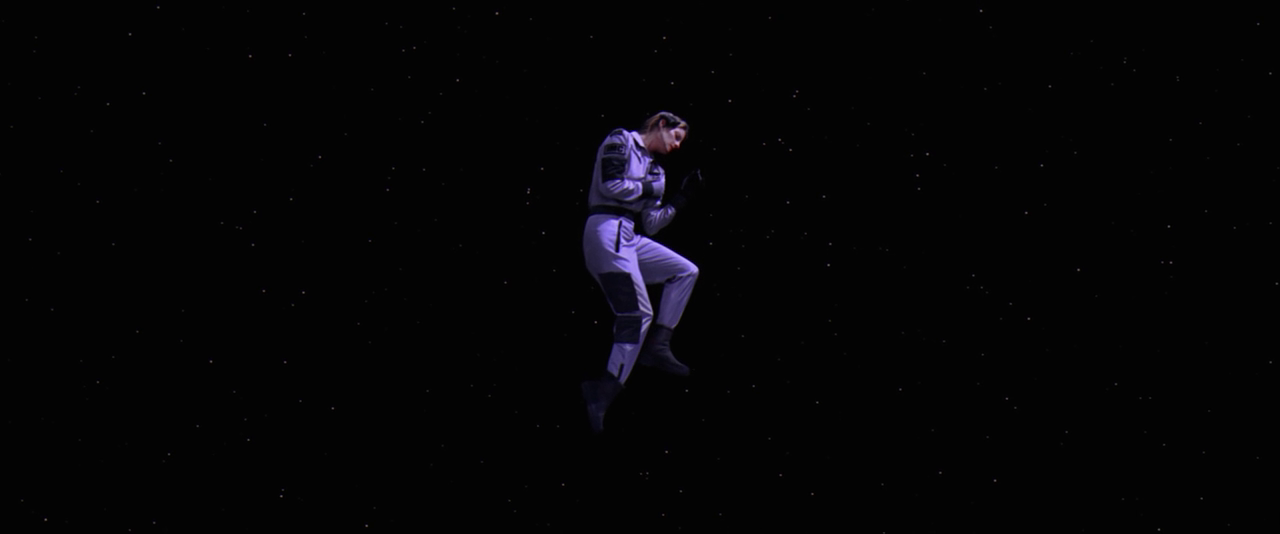

With Gravity, we see the first significant deviation in the astronoetic sequence I’ve selected. Unlike in both 2001 and Contact, space doesn’t figure as an ambiguous Outside, the primal encounter with which proves comforting, transformative, or uplifting. To the contrary, in Gravity, as the opening subtitles starkly inform us: “Life in space is impossible.” The film is an elaboration upon this statement. From the very start, then, the film telegraphs one of its central thematics, namely, that space is an inhumane, terrifying place, totally indifferent to human concerns or scale.

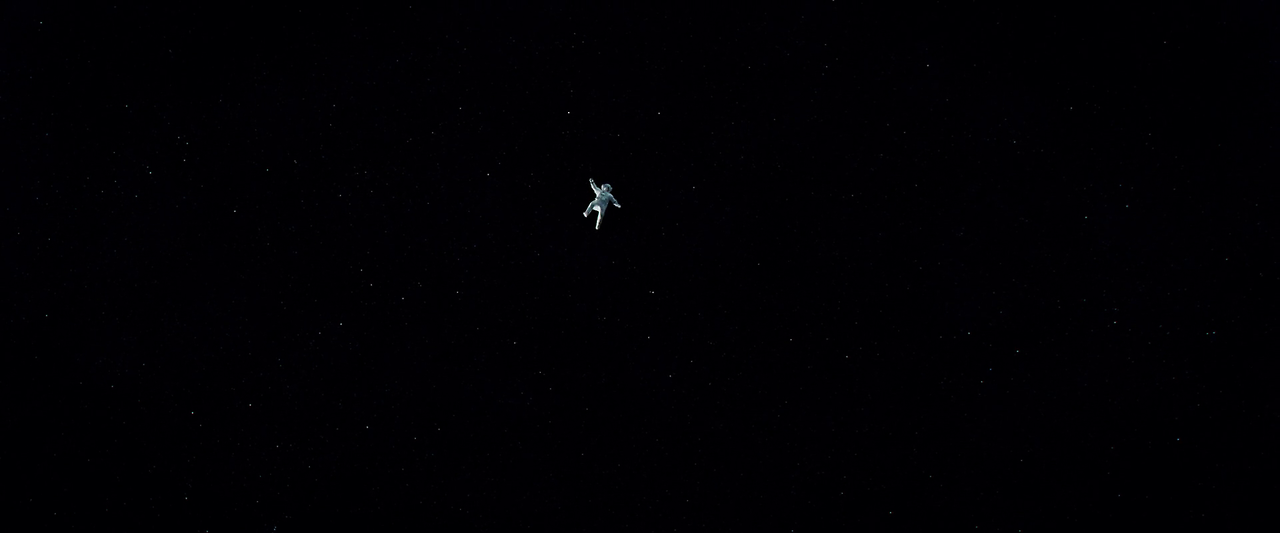

The plot of the film is very simple. Biomedical engineer Dr. Ryan Stone is aboard the Explorer for her first space mission, accompanied by veteran astronaut Matthew Kowalski. After an orbital satellite is destroyed, the debris initiates a chain reaction of additional debris that promptly destroys the Explorer, killing everyone except for Stone and Kowalski. Kowalski rescues Stone after they both become detached, and they spacewalk to the ISS. On the way, it’s revealed that Stone used to have a daughter, who died in an abrupt accident. When they reach the ISS, Kowalski is also lost. After a catastrophic fire, Stone makes her way in a Soyuz toward a Chinese space station in the distance. On the way, she nearly gives up on returning to Earth while speaking with an Eskimo-Aleutian ham radio operator, but a dream of Kowalski’s return forces her to confront her despair. She then marshals her efforts to enter the Chinese station and uses its escape pod to return to Earth’s surface.

The principal architectonic of the film is the parallel between Stone’s emotional and physical journeys. During the first two thirds of the film, Stone exists in a state of literal and symbolic detachment – lost both in her inability to grieve and in space. I say that she is unable to grieve because her response to the death of her daughter is to flee from the trauma – thereby paradoxically holding the trauma in suspended animation – rather than to confront or process it. “I was driving when I got the call,” Stone says. “So that’s what I do. I wake up, I go to work, and I just drive.” The fact of her flight from this trauma is so fundamental that it separates her from the terrestrial altogether. When Kowalski asks her what she likes best about being in space, Stone replies, “The silence. I could get used to it.” Of course, underlying Stone’s emotional isolation is a desperate need to reconnect with the human condition. Much of the film entails Stone’s frantic attempts to make contact with other human beings – with Kowalski, with Houston, with anyone who might be listening down below.

At first, her cries for communication appear as calls for technical aid, but it’s difficult to avoid the realization that what Stone really needs is to grieve.

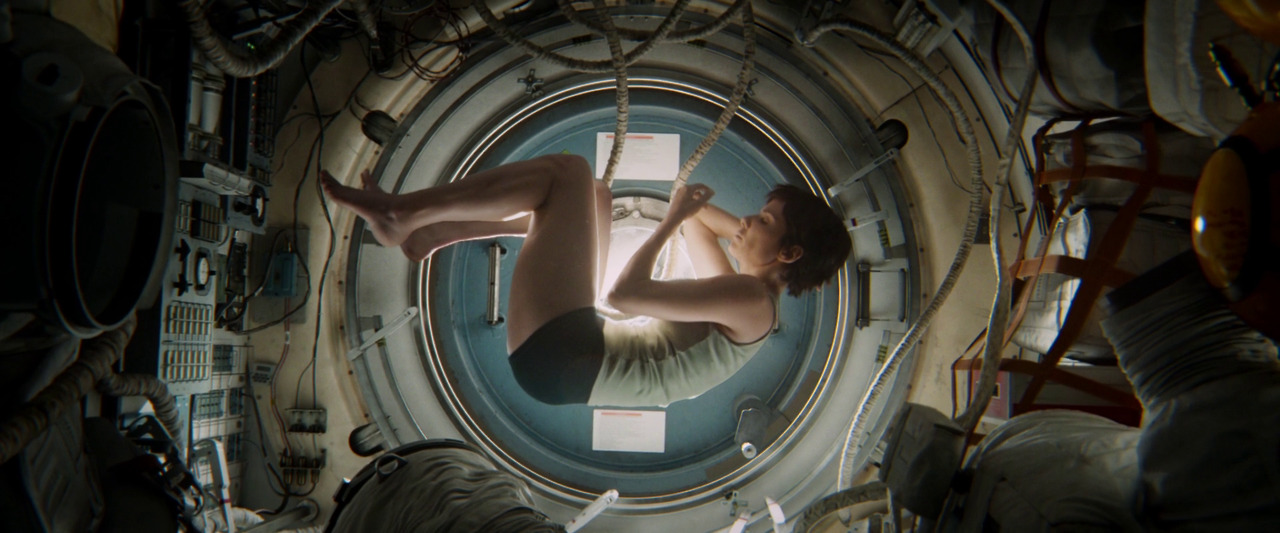

Consider the moment when Stone, foot tangled in a flimsy rope, struggles to persuade Kowalski not to let go of his tether. Kowalski: “You have to let go.” Stone: “You’re not going anywhere.” Kowalski: “It’s not up to you.” On the surface, their concerns are directly practical. If Kowalski does not let go, both of them will be lost in the void of space. However, the sequence of dialog also speaks to Stone’s emotional journey. Her inability to let go, to acknowledge the lack of control over life and death that characterizes the human condition, has driven her into the most inhospitable of places. She is both manic and withdrawn, detethered (indeed, it is difficult to ignore the repeated line of dialog: “Dr. Stone is detached! Dr. Stone is detached!”). There’s a very striking scene immediately after Stone makes it inside the ISS where she draws herself into a fetal position – a very different kind of “star child,” this time helpless and unformed.

After navigating the hostile environment of what is materially the site of a catastrophic accident (paralleling the accidental nature of her daughter’s death), Stone arrives at her zero point.

This takes place in the Soyuz, when Stone makes radio contact with an unidentified speaker of an Eskimo-Aleutian language. They cannot speak comprehensibly to each other, but Stone and the radio operator forge a human connection by imitating the barking of dogs. He sings her a lullaby, allowing her to hear the sounds of his child (contrast the scene with HAL’s final performance of “Daisy Bell” prior to his deactivation). At this point, out of fuel, Stone descends into utmost despair, seeking to commit suicide by turning off the oxygen. The film’s constant visual motif of inversion, or “upside-downness” – previously, we see this motif occur, for example, during Stone’s disclosure of the death of her daughter – appears most strikingly here in the nearly perfect orb of Stone’s floating tear. The contours and orientation of human life become inverted in the hostile void.

It’s after Stone dreams or imagines Kowalski’s return that she overcomes her despair, letting go of the black hole of her daughter’s loss and seeking a return to earthly conditions. Kowalski’s imago here plays a very specific role. On the one hand, he exposes the falsity of Stone’s hope that anyone else will be able able to save her. On the other hand, he vocalizes the seductive appeal of committing oneself to the void entirely. In so doing, he makes Stone’s desire for death external and explicit. In other words, letting go of the former displacement (i.e., the hope of rescue) enables Stone to overcome the latter drive or pull (i.e., toward death, suicide). When Stone abandons the Soyuz and makes her way haphazardly to the Chinese station, using a fire extinguisher for propulsion, it’s no coincidence that this transpires at precisely the moment of sunrise breaking over a dark earth.

During her descent through the atmosphere, Stone’s radio picks up a mélange of signals, a collage of music, news, voices that indicate her return from the inky, silent blackness of the Outside back into the sphere of human meaning. Contrast reentry into this auditory envelope with the cacophonous penumbra that swathes the solar system at the very start of Contact, where the movement of the camera also differs – the camera’s eye in this latter film ostensibly withdraws into the depths of space (only to conclude its journey in Dr. Arroway’s eye) while Dr. Stone descends down into the tumult. The fire of reentry into the world of human concerns licks at her pod, threatening to shake it to pieces. Grief is not a process one is guaranteed to survive. When it lands – veritably as if in Darwin’s warm pond – Stone must exert herself one last time.

This time, she ascends through the green, vital murk, following the trajectory of evolution from the depths of primordial soup where life originates – up, up, up toward the sun. She thrashes free of her spacesuit, swimming to the surface in motions paralleling the frog that passes her by. On the sandy shore, she crawls on her belly before, shaking, she ascends further onto all fours, onto her feet, finally standing upright, the camera looking up at Stone, triumphantly alive and indefatigably human.

As with all of the films I’ve assembled here, Gravity poses an argument within the domain of astronoetics. For the film, the human condition is resolutely tellurian. We are earthly creatures first and foremost, and while the Outside may tolerate brief incursions, it does not welcome them. (It would be intriguing to compare elements of Gravity with Cordwainer Smith’s famous short story “Scanners Live in Vain” [1950], in which the “First Effect” of human space travel consists in what Smith calls the “Great Pain of Space,” necessitating that spacefaring crews have their brains damaged so as to expunge all human feeling. Contrast this with the Guild Navigators in Frank Herbert’s Dune series [1965-1985], who exist as worm-like posthumans confined to spice-saturated tanks, where they dream safe passage for spaceships, or even the astropaths of Warhammer 40,000, who perform a similar function: in all cases, the baseform human is maladapted to space travel.) There is a humanism here, then, but one which rejects the transformative paternalism of 2001 and Contact. In Gravity, gravity always wins: either return to the terrestrial center as part of your journey of reconciliation (with the Earth, with life, loss, the past, the trauma of finite selfhood), or else be destroyed by your attempt to escape it. Within the film’s field of meaning, nothing could be worse than such an escape, for it would be a ceaseless, oscillating trajectory into the inhuman, into infinite darkness.

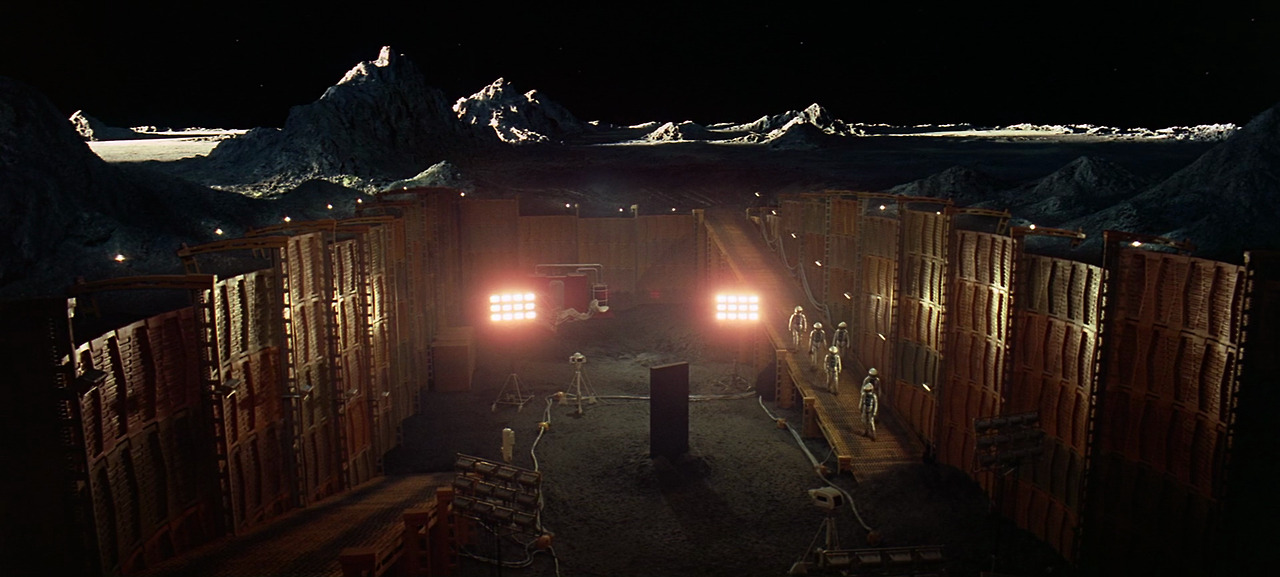

Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014)

Interstellar enlarges the anthropocentric vision of Contact into a full-blown anthropological myth of human dominion over nature that founds itself upon the primal self-creation of the human. It’s interesting to note the degree to which the film synthesizes vocabularies of popular scientism and deracinated Christian dialectics. The former occurs not only in the immense attention to technical detail evident throughout the film – largely employed to detail memorably elemental planetary settings, as well as to justify its denouement – but also in the plot itself, summarized as the need for humanity to abandon an exhausted Earth and apply itself to the exploration of space. The latter vocabulary provides the motive force of the film, however, contrasting the subtle evil of a deterministic, entropically saturated nature with the overwhelming power of love. Let’s see how this unfolds.

The film begins by contextualizing its setting. Earth is afflicted by a slowly escalating crop blight, the causes of which, curiously, are abstracted from any possible ecological reason. We’re in the domain of a Dying Earth narrative here, not a climate change apocalypse. The difference between the two is that the former isn’t anthropogenic. This matters in Interstellar because it warrants the disdain for earthly caretaking exemplified by engineer/pilot Joseph Cooper’s charismatic go-get-‘em libertarian space cowboy restlessness (contrast Cooper with the protagonist Allie Fox in The Mosquito Coast [Peter Weir, 1986], whose strikingly similar personality leads him into tyranny and destruction). It’s not that humans have damaged the planet – thereby implying that humans might be able to learn to adapt or mitigate the damage they have caused – but that planetary conditions ultimately have failed us. “You don’t think nature can be evil?” Cooper later inquires of Brand, surprised.

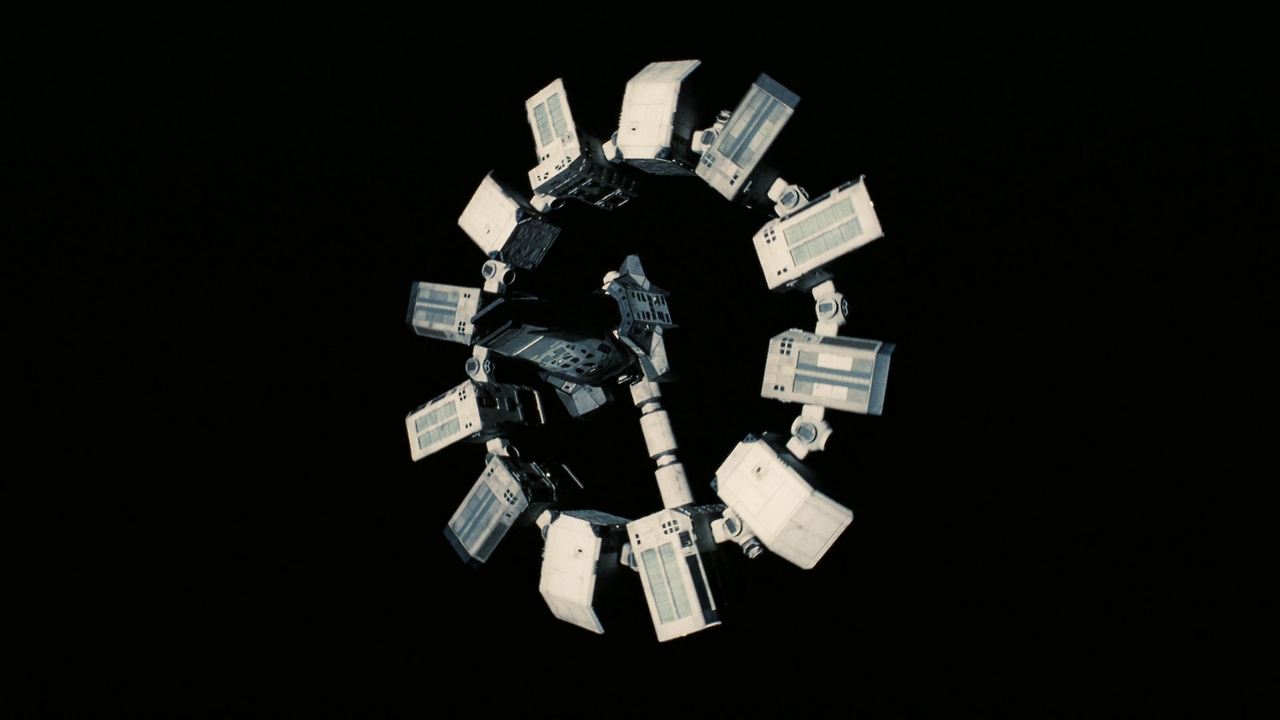

Resentfully (“It’s like we’ve forgotten who we are, Donald. Explorers, pioneers, not caretakers”), Coop (widowed) works a farm with his stepfather and two children, Tom and Murphy. After encountering the remnants of NASA, Cooper agrees to pilot an exploratory mission to an artificial wormhole discovered in orbit around Saturn. On the other side of this wormhole, Professor John Brand informs him, there are potentially inhabitable planets, as well as three human scouts sent ahead to investigate. There are two options for mission completion: Plan A (Professor Brand will solve an equation he’s been working on, achieving the theoretical grounds for a gravitational theory of propulsion) or Plan B (Cooper and his crew, including the Professor’s daughter, Dr. Amelia Brand, will endeavor to colonize a viable planet with the cargo of embryos loaded onto their ship, the Endurance).

Cooper’s departure deeply aggrieves his daughter, Murphy, although Cooper promises to return. In the background of the narrative, there are a series of gravitational anomalies centered on Murphy’s bedroom (e.g., resulting in both the provision of the NASA base coordinates and the scrambling of nearby navigational computers), although no one investigates this thoroughly. The young Murphy wonders if it is a ghost, while Cooper and others dismiss her observations – including the spelling out of the word “STAY” when Cooper informs Murphy of his imminent departure.

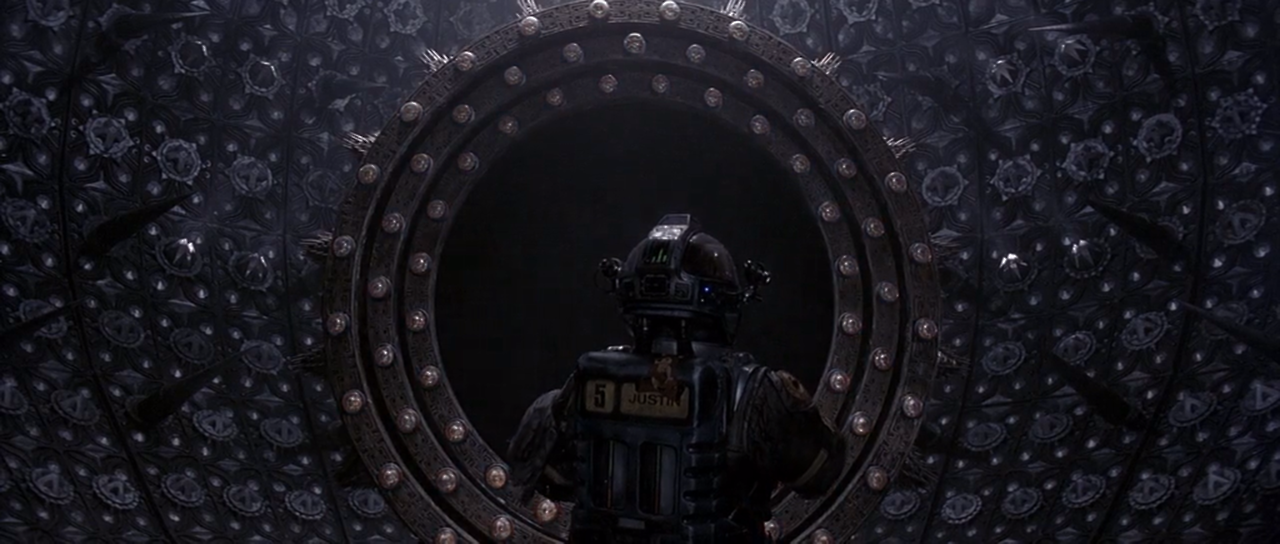

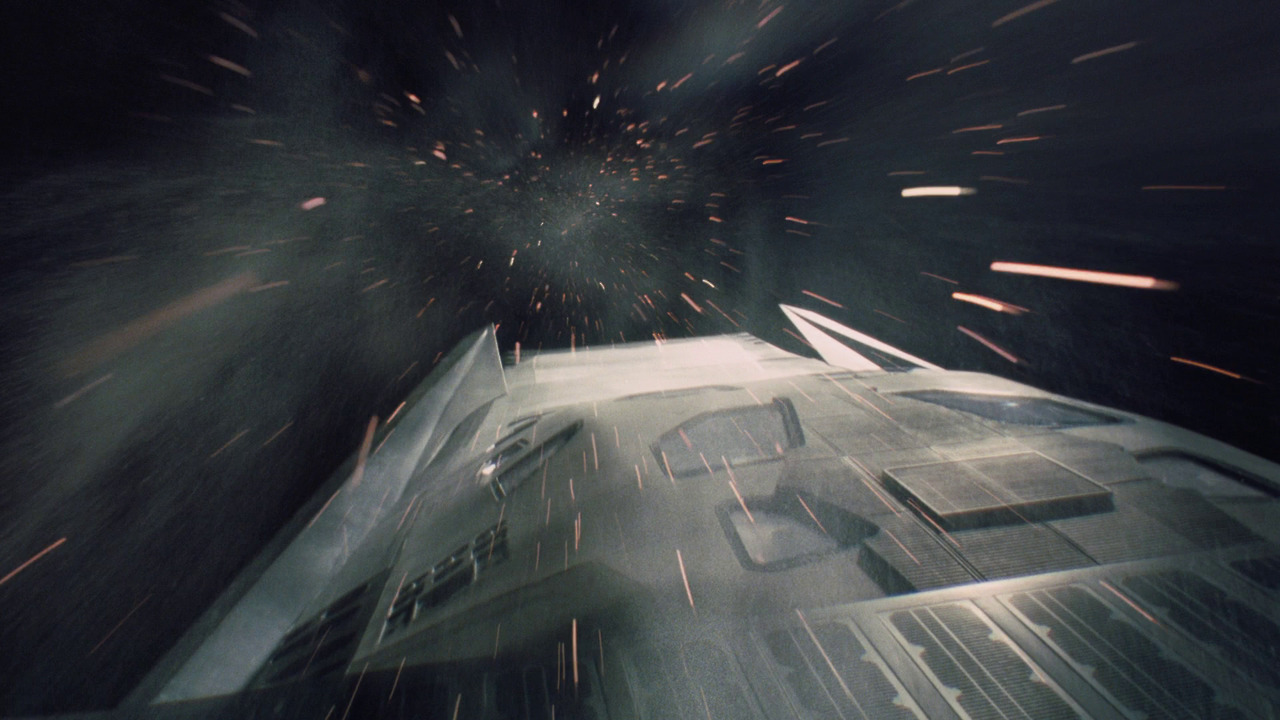

The Endurance enters the wormhole, at which point Dr. Brand apparently makes contact briefly with a mysterious being residing therein. In the new galaxy, Cooper and his crew decide which of the three potential planets to visit first.

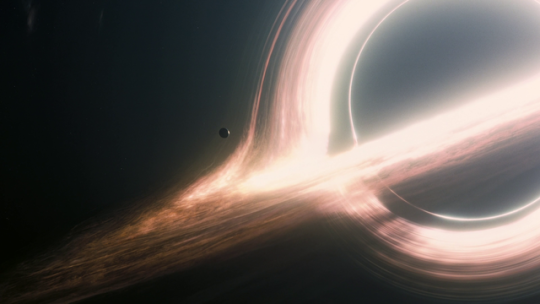

Located in a gravity well near a black hole, visiting the surface of the first planet entails a price – in time. Due to the circumstances of relativity, every hour on the surface translates to seven years outside of the well. Accordingly, when the planet is discovered to be beset with monstrous waves making it uninhabitable, the cost of the expedition ends up at twenty-three years. Cooper and Brand are devastated, and the melancholy tone of the messages received from Earth in the interim only sharpens the difficulty of their circumstances. Murphy sends a bitter message to Cooper, informing him that she is now the age he was when he left home.

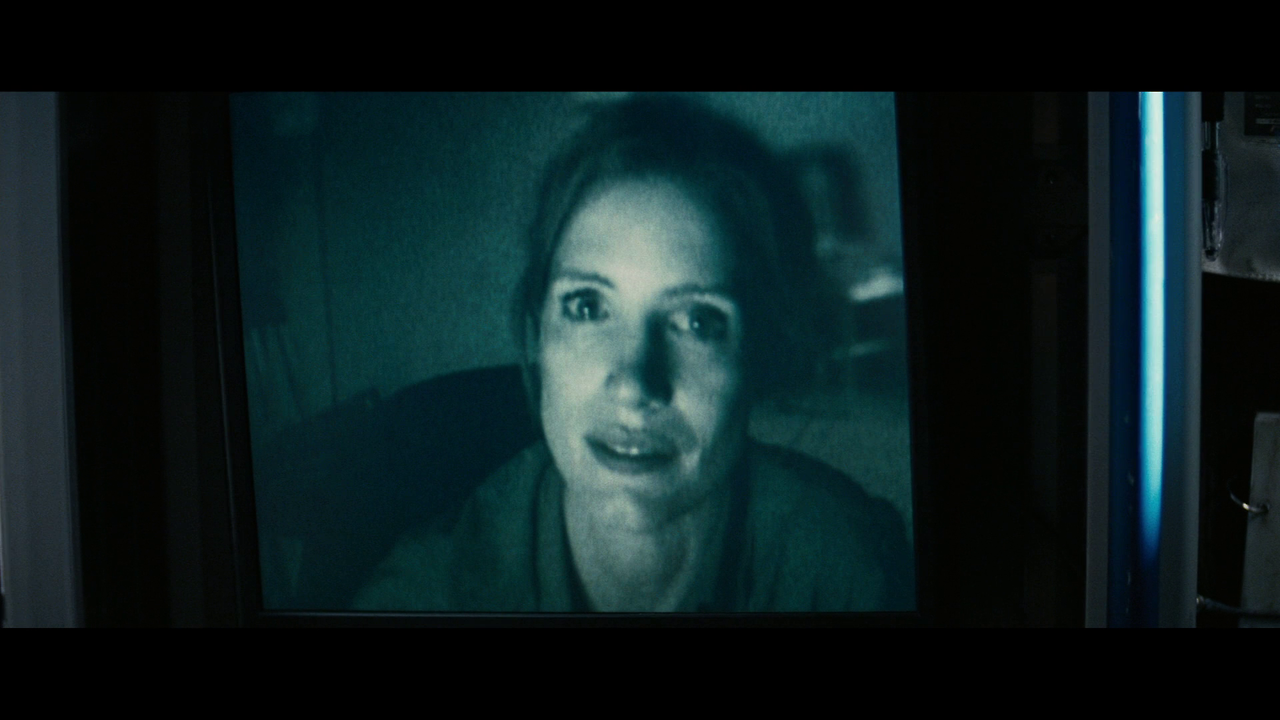

The Endurance departs for the second planet, although this expedition is significantly more catastrophic. They encounter the surviving scout, Dr. Mann, but he intends to hijack their spaceship in order to save himself. This misadventure results in the death of the remaining crew, save for Brand and Cooper, as well as notable damage to the Endurance. This makes return to the Milky Way impossible. Meanwhile, back on Earth, Murphy has become a physicist under the tutelage of Professor Brand, but he reveals on his deathbed that Plan A was never possible, since his equations lack necessary but unobtainable quantum data. Plan A was always a lie, intended to comfort those left behind by the Endurance. Murphy is distraught (“I just want to know if you left me here to die,” she rails at Cooper in another video dispatch).

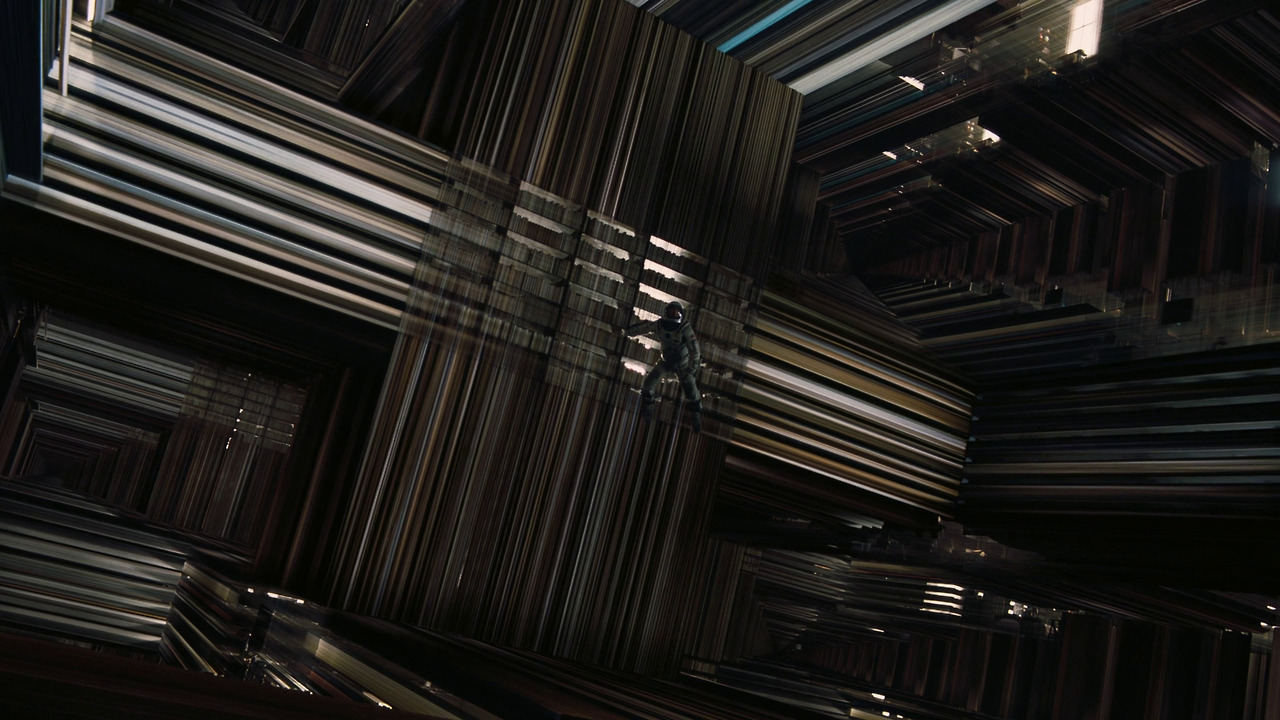

In the new galaxy, Cooper severs the wreckage of the Endurance from Dr. Brand and her cargo of embryos, slinging her onto a trajectory toward the third planet and away from the black hole. Trapped by gravity, Cooper descends into the black hole.

There, he finds himself within an artifact called the Tesseract, which he discovers to be a four-dimensional environment co-located with Murphy’s bedroom at every possible moment in time. At first, Cooper despairs, stuck in a repetitious superposition and forced to observe scenes from his former life, but after manipulating tensile threads of spacetime to transmit a message (“STAY”), he realizes that the Tesseract enables him to transmit the quantum data needed for the solution of Professor Brand’s equation. All that is needed is for Murphy to notice the small ways in which Cooper sends the message – e.g., through binary expressed in gaps in a bookshelf, through lines of falling dust.

In the present, a grieving Murphy returns to the Cooper household to persuade her brother to leave. Visiting her childhood bedroom, she has a sudden epiphany, realizing that, somehow, Cooper’s been communicating with her for her entire life. She transcribes the quantum data and solves Professor Brand’s equation, thereby enabling human diaspora from Earth. Cooper realizes that the Tesseract must be an artifact constructed by future humanity (“People couldn’t build this.” / “Not yet”) to ensure the transmission of the quantum data, thereby embodying a temporal “strange loop” in which the future secures its existence by producing its own past. If this seems confusing, consult a similar temporal loop in Predestination (Michael and Peter Spierig, 2014), in which a similarly self-referential narrative of self-creation telegraphs more emphatically the underlying antagonism toward dependence that author Robert Heinlein wrote into his original short story (“The Snake That Eats Its Own Tail, Forever and Ever. I know where I came from – but where did all you zombies come from?”).

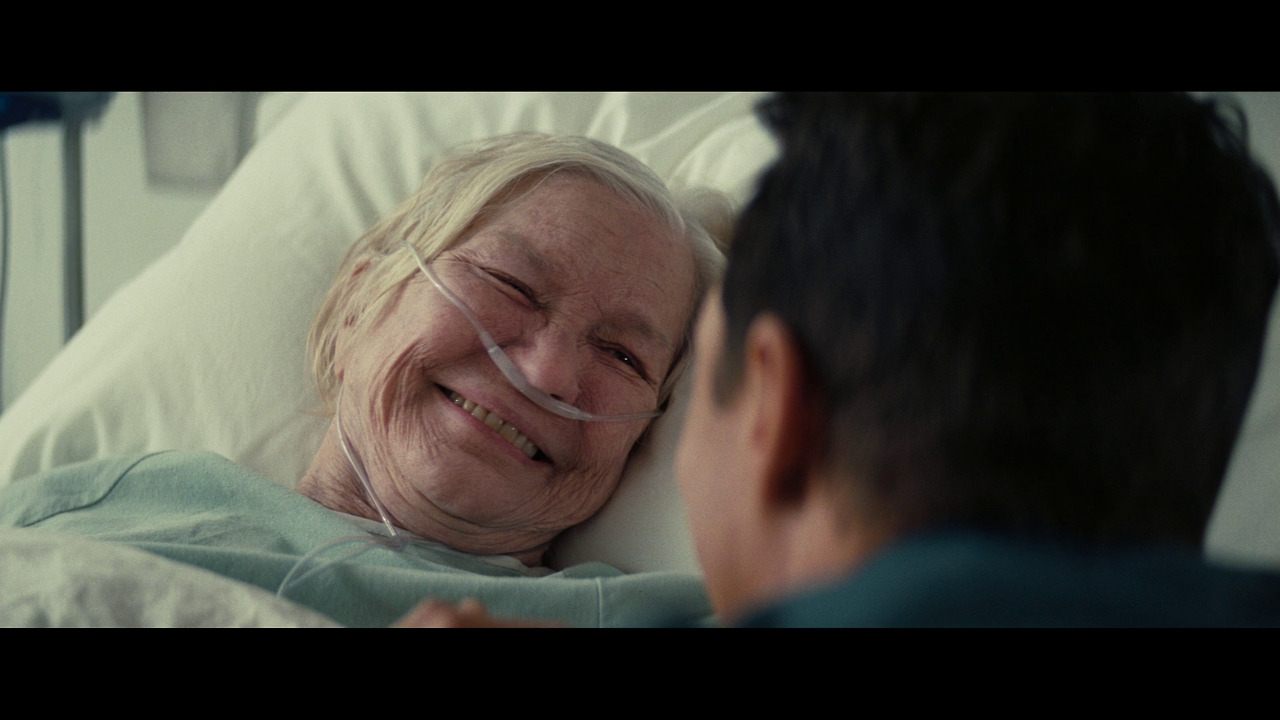

In the epilogue, Cooper is ejected into space (by passing through the wormhole, where he reaches out to touch Dr. Brand in the Endurance as she travels to the new galaxy), but soon he’s picked up and taken to a space habitat orbiting the wormhole. Informed that decades have passed, he learns that Murphy’s solution of the equation enabled humanity to depart Earth and survive. He meets with an aged Murphy for a final reconciliation before again departing through the wormhole to find and help Dr. Brand with the new colony.

Something astonishing about Interstellar is the degree to which the film causally places Cooper at its narrative center. He is positioned as the savior of humanity, whose paternal love and presence subtends the entire film in multiple dimensions simultaneously. Much like the imputed need for humanity to leave behind Earth in order to secure its future, Cooper’s apparent abandonment of his family for the stars is precisely the mechanism that both ensures their survival and returns him to them, albeit briefly: “We have to shed the weight to escape the gravity. […] The only way humans have ever figured out of getting somewhere is to leave something behind.”

There’s something structurally narcissistic about this structure. Cooper’s descent into the black hole results not only the discovery of meaning, or a resolution of an emotional or technical problem, but in the discovery of… himself. Effectively, Cooper creates himself – out of himself – to encounter himself – to save himself. Likewise, what obtains for Cooper obtains for humanity, which effectively exists in Cooper’s shadow, as it is his journey of self-creation that saves and uplifts humanity. Even Murphy’s apparent solution of Professor Brand’s equation is merely a transcription of the quantum data Cooper provides. This effectively reduces her position in the film to that of a mere stenographer, and her resentment for her father reveals itself to be only a lack of faith in his efficacy (his late comment to Murphy “I was your ghost” reflects and inverts his early lament to her that “Once you’re a parent, you’re the ghost of your children’s future. […] Murph, look at me. I can’t be your ghost right now. I need to exist.”).

The subsuming dialectic between love and nature foregrounds itself constantly. As noted above, terrestrial nature always figures as an antagonist, be it Cooper’s wife’s brain cyst, the Earth’s failure to provide for its occupants, the mindless cruelty of the two uninhabitable planets, and even the drives of the “natural” human as articulated by Dr. Mann. “The survival instinct,” he exposits while he and Cooper struggle. “That’s what drove me. It’s what drives all of us. And it’s what’s gonna save us.” The film dramatically negates this claim, however, elevating love to the position of a cosmic force. As Dr. Amelia Brand argues in a key scene: “Love isn’t something we invented – it’s observable, powerful. Why shouldn’t it mean something? […] Maybe it means more – something we can’t understand, yet. Maybe it’s some evidence, some artifact of higher dimensions that we can’t consciously perceive. I’m drawn across the universe to someone I haven’t seen for a decade, who I know is probably dead. Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space. Maybe we should trust that, even if we can’t yet understand it.” Likewise, Cooper in the Tesseract: “It’s just like Brand said. My connection with Murph, it is quantifiable. It’s the key!”

In astronoetic terms, Interstellar culminates with the effective elimination of nature, conceived entirely in terms of constraint and impingement, in lieu of humanity’s dominion over its conditions. As Cooper relates, “Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here.” The identification of earthly conditions with death, with natural evil, gets sublated into the bright future made possible through love – specifically, the power of paternal love (the child-like dependence or the need for assurance found in Contact gets wholly inverted here). Culturally, Interstellar directly abuts the virulently anti-ecological attitude engendered by manic techno-optimism. In no small part, this is evident in how its disdain for caretaking (of any kind) gets endorsed and justified by its invocation of humanity’s destinal departure from the conditions of dependence. Hence why Cooper is always departing. Unintentionally, the film consumes itself. Murphy: “You go.” Cooper: “Where?” Murphy: “She’s out there, setting up camp. Alone in a strange galaxy. Maybe right now she’s settling in for the long nap, by the light of our new sun. In our new home.” But the conditions of home are impossible here. Humans have no home in nature, only in its conquest, and that constitutes a process of accelerating expansion that structurally precludes any terminus. Consider the road movie Vanishing Point [Richard C. Sarafian, 1971], in which Kowalski, a freelance driver, drives across the country at increasingly high speed, refusing to stop because it’s only in the process of infinite acceleration that he can sustain his need for meaning (= speed). Of course, the film concludes with Kowalski’s decision to crash into a roadblock intended to stop him, preferring the freedom of death to deceleration. There’s no posthuman speculation here, as there is in J. G. Ballard’s novel Crash (1973, “two semi-metallic human beings of the distant future making love in a chromium bower”). Kowalski is a true nihilist; perhaps so is Cooper.

I turn to Prometheus and Alien: Covenant in part two (“Astronoetic pessimism and the posthuman: Prometheus and Alien: Covenant as philosophy“).