“[…] exit becomes possible only if we divest ourselves of the libidinal constraints and demands we inherit from the civilization into which we are thrown.”

0. INTRODUCTION

Forty minutes into Alex van Warmerdam’s Borgman (2013), we find the pivotal scene. Marina – one half of a well-to-do Dutch couple – crouches in the garden shed, frantically sweeping at a pile of spilled potting soil. Realizing that the gardener’s been murdered, she’s trying to hide the evidence. Her husband Richard appears, and she makes a hasty excuse for the mess. Richard: “But, darling, you don’t need to tidy that up. That’s what the gardener is for.” She tells Richard that the gardener resigned that afternoon, even though she clearly knows otherwise. Abruptly, she breaks down, clutching at Richard. “Oh, Richard. I’m so sorry. You are my only real love. You know that, don’t you? […] Sometimes everything seems unreal to me. […] There is something that surrounds us. Something that is outside us, but slips in now and then. A warmth. A pleasant warmth that intoxicates, but also confuses. The shell of something that means harm. At least that’s what I think. I’m not sure.” “That’s a delusion,” Richard replies, trying to assuage her anxiety. “It’s tiredness. You work too hard.” She begins to weep. “I feel so guilty. We have it so good. We are fortunate. And the fortunate must be punished.” Richard resists whatever insight she might be trying to voice. “That’s nonsense. We were born in the West, and the West happens to be affluent. We can’t help it.” The appearance of their three children interrupts this brief dialog, and Marina hastily conceals her tears.

The scene is pivotal because it shows one of the few moments when Marina – ostensibly the film’s protagonist – seems even remotely aware of the reality of her family’s predicament, even as she buries that awareness in self-pity and sentiment. It’s a fundamentally political predicament, and this gets us to the heart of my claim about Borgman, which is that the film does two very important things primarily.

First, the film advances a critique of civilization by means of its disruption. Throughout the film, civilization figures both as product and as process. On the one hand, civilization gets exemplified by the brutalist, ultramodern suburban estate where Marina and Richard reside and by the stark opposition of this estate to the forest – the “beyond” or the “outside” (Latin: foris) – from which Camiel Borgman arrives. On the other hand, civilization in this sense is an ongoing process. Civilization takes place – for example, by clearing the wild, by driving out its feral inhabitants, by erecting and maintaining gardens in lieu of forests. It is precisely the apparent domestication of the Outside that makes possible the quietly monstrous domestic scene that serves as the film’s central site. Recall Walter Benjamin’s observation: “Every document of civilization is a document of barbarism.”

Second, the film proposes a mode of exit – something like a forest passage. At least two things get left behind along the way. On the one hand, Camiel and his companions disrupt the domestic scene in order to enable a departure from it. In the film, this departure is both figurative and literal. Some of the characters – but neither Marina nor Richard – leave the estate itself, but they also leave behind its legacy of repression, its ressentiment, its uniquely stultified and stultifying violence. It is crucially important that this departure is not enabled by the return of the repressed. There is no collapse into anhedonia following some libidinal breakdown, as in Michael Haneke’s Der siebente Kontinent (1989), nor is there an orgy of violence baring the hidden truth of bourgeois rationality, as in Jean-Luc Godard’s Week-end (1967). Rather, those who depart divest themselves of the logic of repression altogether – and, therefore, of the logic of its return. They abandon the libidinal ruse of identity as a given image (or a graven image). Call this ruse existence as a certain sort of late modern subject. In other words, there remains a crucial sense in which, to depart, you must leave yourself behind – in order to become another (“becoming inhuman”). A forest passage, like a rewilding, changes the very landscape it traverses.

Hence, surprisingly, the film carries out a process of deromanticization in which relational forms and even the very substance of association are revised in accordance with the logic of the Outside. This is surprising because exit proposals typically retain strongly romantic overtones. As in the films of Terry Gilliam (or, memorably, in George Lucas’s student film THX 1138 [1971]), escape from civilization, or modernity, or rationality – to wit, Max Weber’s “iron cage” – is an adventure, a journey, a quest. You’re either breaking out of a prison, or waking up from a nightmare. At the very least, you can imagine that you are. In contrast, Borgman doesn’t tell you that escape is the royal road to self-discovery. Rather, it tells you that exit becomes possible only if we divest ourselves of the libidinal constraints and demands we inherit from the civilization into which we are thrown. Here, Marina misidentifies a coldness as a warmth; consider the phenomenon of paradoxical undressing. There is a desperate need for a kind of incision, but this incision cannot be forced upon you by the real, only solicited from it, only undergone. Hence, the amoralism of Borgman’s pagan political theology can be unsettling – indeed, it is intended to unsettle the placid assumption that transformations come without consequences or difficulty. Although it remains ambiguous, Borgman’s own violence may be a requisite function of disrupting the violent logic of Marina and Richard’s form of life.

In short, my claim is that Borgman shows us what a politics of exit looks like. It’s showing us the door – a way out of the miserable labyrinth of late modern capitalist civilization. Probably, we were already dreaming of its destruction; now: Camiel Borgman is here.

Let’s start from the beginning.

“Marina searches the grounds, presumably for Camiel. In the summer house, she encounters a pale hound. Overwhelmed by a sense of the uncanny, she whispers, ‘Camiel?’”

1. WHAT HAPPENS

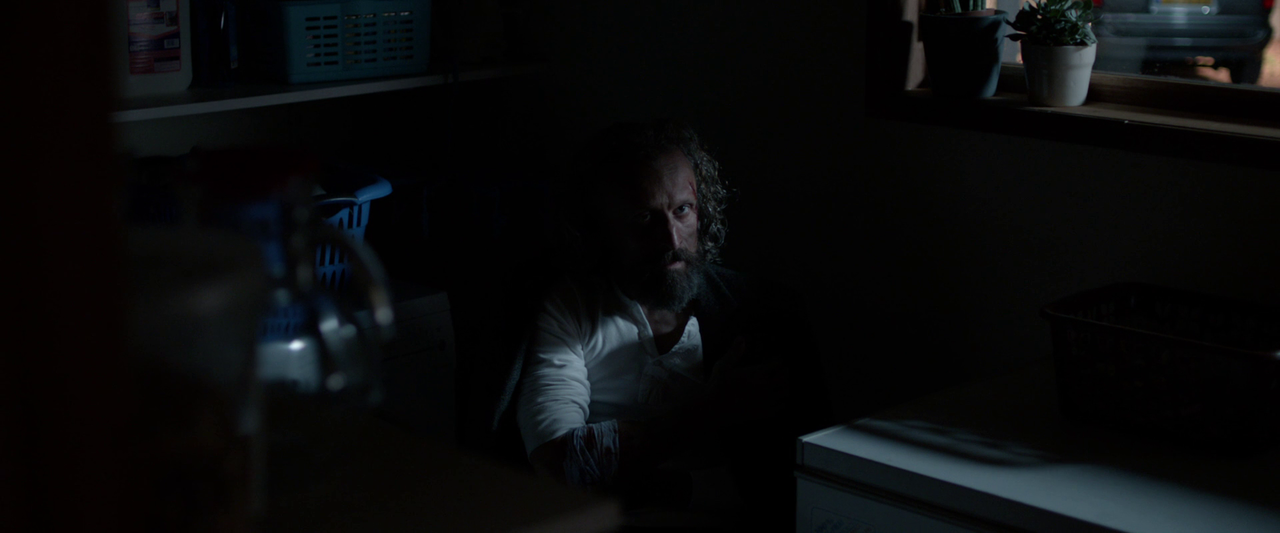

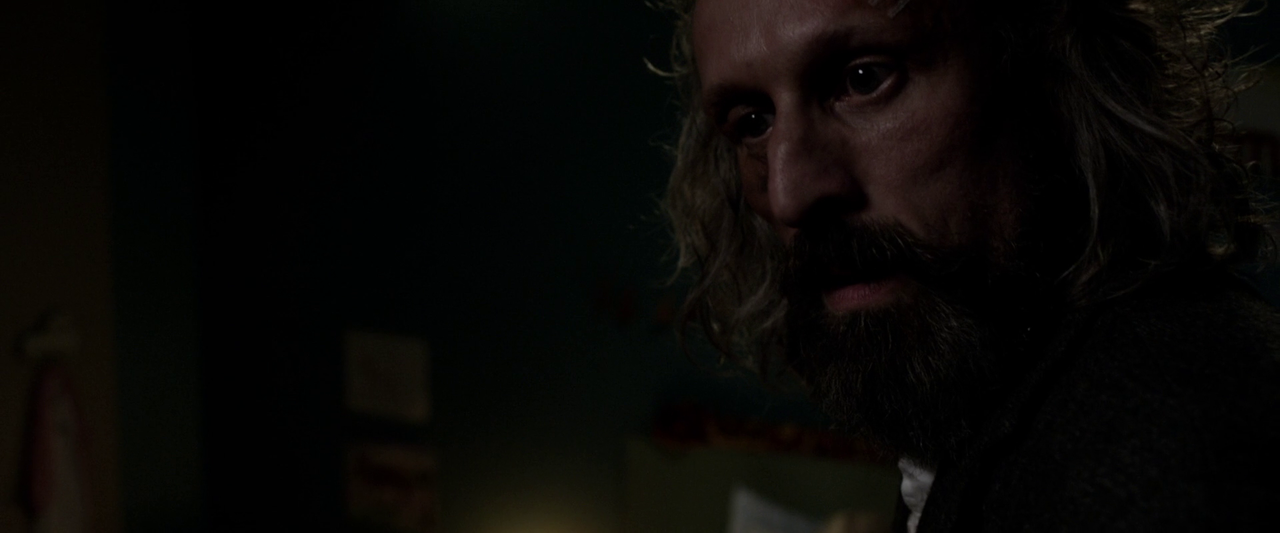

Borgman starts with a blacksmith, a forest warden, and a priest, all of whom arm and steel themselves, preparing for a mysterious incursion into the forest. Arriving with purpose, they seek violently after concealed warrens, stabbing at the earth with long metal poles. In one of these warrens we meet Camiel Borgman, a raggedly hirsute character who has prepared for such an ousting. Gathering his scant belongings, Camiel hurriedly tries to make a phone call or two, then flees through a tunnel. Sprinting through the woods, Camiel stops twice at similar warrens to warn his companions, Ludwig and Pascal, both of whom are sleeping.

Leaving the forest behind, Camiel stops briefly at a gas station restroom before starting to wander through an affluent suburb, looking vaguely lost. He knocks on the front door of a nearby mansion, asking for a bath, but he is instantly rebuffed. Looking rather haggard, he arrives at Marina and Richard’s estate, a fashionable concrete bungalow with extensive grounds. He sees Marina opening a window. After Camiel rings the doorbell, Richard answers the door. Again, Camiel asks for a bath, but Richard refuses, despite Camiel’s persistence (“I’m just a traveler who needs a wash”). On the verge of departing, Camiel claims to know Richard’s wife, Marina, who promptly arrives to investigate the cause of Richard’s increasing annoyance and volume. Marina doesn’t know Camiel, although he continues to assert their familiarity, nearly guessing her name and alluding to a prior encounter in a hospital where she had served as his nurse. Baffled, Marina repeats her denial, and Richard loses his temper, goaded by Camiel’s insistence. Enraged, Richard attacks Camiel, beating him with such violence that Marina is deeply horrified. He seems nearly as angry with her as with the stranger on his doorstep, demanding to know whether or not she knows Camiel. She denies it. Outside, Camiel disappears.

Shortly after, Stine, the Danish au pair, arrives with Marina and Richard’s three children. We see Richard read a story to his children, then depart for work to address some crisis. After he leaves, Marina notices a light in the garden shed. She finds nothing there, but, after returning to her glass of wine, she encounters Camiel hiding in a utility room. He announces himself: “I’m here.” First treating his injuries, Marina brings Camiel into the house, where they run into Stine, who Marina promptly swears to secrecy: “He’s a man from the street. A tramp. I’m going to let him have a shower, give him something to eat. You better not tell my husband. It would upset him.” After his bath – and here we first see Camiel’s mark, a distinct scar upon his back – Marina ushers him to a small summer house nearly at the forest’s edge, where he is allowed to spend the night.

Come morning, Marina rejects Richard’s affection, and the day begins with the minor sickness of their youngest daughter, Isolde. She sees Camiel creeping around the house, telling her mother sleepily, “I saw a magician.” After Richard leaves for work, Marina asks Camiel to leave, but he implores her to let him stay in the summer house while he recovers. She relents. Camiel receives a text message: “Has the time come yet?” No, he replies. Later, Marina and Richard briefly discuss the previous day’s altercation. “He wasn’t too bad, I thought,” she says.

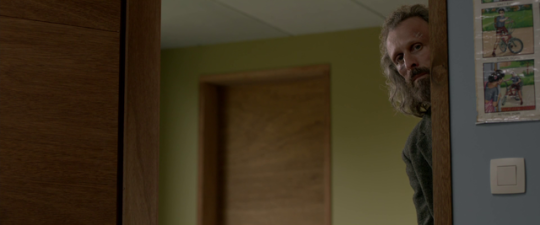

A day or two passes, and Marina is working on a piece of art in her studio when Camiel appears (“I’m here”), asking for a bath in the house, which she grants. There, Isolde encounters Camiel for the second time, totally nonplussed at his presence in the bath. His presence is now part of her world, and he offers to tell her a story later. Richard’s abrupt arrival causes a brief panic as Marina tries to prevent him from discovering Camiel. A panning shot shows us Camiel avoid the encounter with preternatural smoothness, timing his departure from the house with ease. Richard has brought Marina an extravagant gift, a jeweled necklace, presumably to placate her concerns about his “fanaticism” during the altercation.

That night, Marina takes Camiel’s dinner out to the summer house, but finds it empty. Looking back at the house, she sees Richard asleep in his chair, but the sudden appearance of two dark hounds beside him surprises and disturbs her, for the family has no pets. The hounds scope out the house. Meanwhile, Camiel is telling the children a story. When he sees the hounds, he hisses at them. “You’re early! Off with you!” Marina searches the house, but finds no hounds, instead stumbling upon Camiel in the children’s room. “Isolde was crying. She had a nasty dream,” he whispers. “There was unrest. Now it’s alright.” She shoos Camiel away, angered by his intrusion, still confused by her sighting of the hounds. She sees them outside, trotting down a pathway and off into the night.

Suddenly: Richard is violently beating Marina – but this is revealed to be a dream. As Marina dreams, Camiel, naked, crouches over her supine form, a clear visual citation of Henry Fuseli’s popular 1781 oil painting The Nightmare.

The next morning, an irritable Marina berates Stine for her tardiness: “I’m warning you, Stine. There are ten others to take your place” (the labor reserve army). After brushing off Richard on his way to work, Marina goes to the summer house only to discover that Camiel has left. She runs into the forest, apparently frantic, then glimpses his retreating figure. “Why are you leaving?” she asks. He shrugs. “I’m bored. I want to play.” “Don’t you want to stay?” “Not if I have to hide.” Marina refers to Richard’s ignorance about Camiel’s presence, and Camiel clarifies that this is precisely why he’s leaving. Now, it is Marina who implores Camiel. “You mustn’t go. Can’t you come back in another capacity?” “It’s possible,” he concedes, appraising the situation. “But it will have consequences.” He inquires about the gardener.

Shortly thereafter, Camiel calls up two of his companions – Brenda and Ilonka – to help him execute a plan to poison the gardener and dispose of him properly. Brenda and Ilonka pretend to be doctors (“You must look civilized, immaculate”) in order to gain access to the gardener’s house, where Camiel has brought the agonized man after surreptitiously shooting him with a blow dart. Promptly, they kill both the gardener and his wife, submerging their heads in concrete and depositing the bodies in a distant lake. On their way to the lake, Camiel drives past Ludwig and Pascal, apparently irritated with them, although he soon calls them with instructions to help him get hired as the new gardener.

At this point, the pivotal scene described above occurs. Later that day, Marina and Richard are bathing together. He expresses some anxieties about his job (Stornebrink, his boss, is “trying to squeeze me out, the bastard”), and Marina casually mentions that several applicants for the gardener’s position will be arriving the next day. As it so happens, each of the applicants is black, and Richard rejects them all, barely bothering to disguise his racist disdain. It’s all a ruse, however, staged by Ludwig and Pascal to ensure that Camiel is hired. They squat in the forest outside the estate with the pool of “applicants,” although the plan nearly goes awry when a random (white) applicant appears. Ludwig promptly knocks him unconscious.

Camiel then arrives, freshly shaven and well-groomed, and he inquires about the position, his meeting with Richard at the door paralleling their first encounter. “Good afternoon. I’m offering my services as gardener.” Richard does not recognize him, although Marina seems both pensive and troubled by his arrival.

While Camiel and Richard walk the grounds, Stine returns with the children. Isolde sees the body of the random applicant in the woods. The children see Camiel and exchange understated waves. Certainly they know who he is, but they make no comment to anyone. Camiel and Isolde exchange a long, enigmatic glance, and she scurries off to find the man in the woods, ending his life with a flat stone.

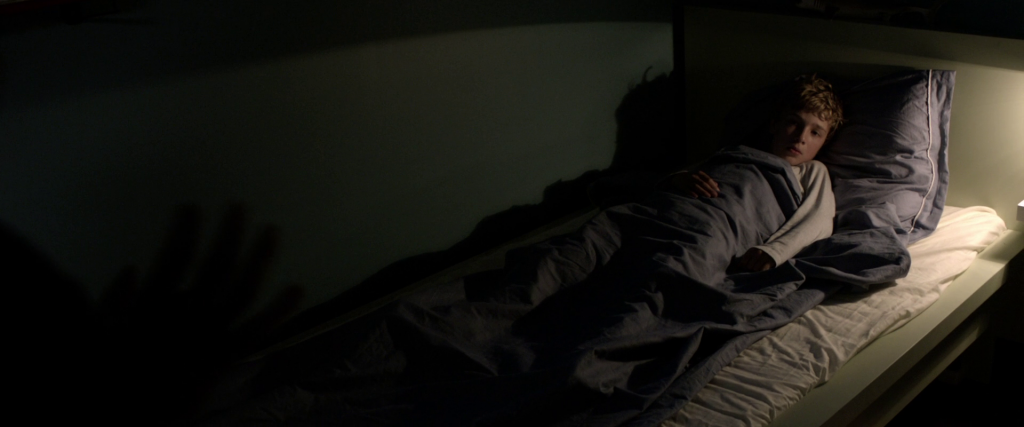

Meanwhile, Camiel gets the job. Marina and Richard offer him a room in the guest wing, which he accepts. That night, confused and restless, Marina leaves her bed and goes to spy on Camiel as he rests quietly. Why did she ask for him to return? Why is he here? Is there to be an affair?

On the way back to her bedroom, Marina discovers one of Isolde’s toys, a teddy bear that Isolde gutted and filled with sand. The next morning, as Camiel begins to garden, Marina scolds Isolde for treating the toy so irresponsibly. Elsewhere, Brenda and Ilonka dispose of the random applicant in the same manner as the gardener and his wife, and Ilonka goes swimming in the lake. We see a mark similar to Camiel’s on her back, a vertical scar left by an incision.

Back at the estate, Marina is trying to solicit Camiel’s attention. Taking him offerings of food and drink, she follows him around the garden, apparently baffled by his impersonal treatment of her. “Are you done?” he asks, visibly irritated. “I am the new gardener. I have an assignment.” “You wanted to play, you said,” Marina responds, confused. “I am playing,” he replies.

Several days pass, during which time Stine asks Marina if her boyfriend may spend the night. Marina refuses (stating, ironically: “I want to know what I’ve got under my roof”), but she invites him over for dinner. Meanwhile, Ludwig and Pascal arrive, ostensibly as Camiel’s assistants, and colonize the summer house. Camiel finds time to continue telling the children a story.

Again we see Camiel, crouching naked (like an Alp) over a dreaming Marina. When she awakens, distraught, she bitterly chastises Richard for his actions in her dream. “Why are you doing this? Why in God’s name? Do you hate me that much?” She leaves the bedroom, stumbling to the guest wing, where Camiel, Ludwig, and Pascal are watching television. She knocks on the window, demanding Camiel’s attention. Camiel invites her inside, but she refuses. “I can’t bear it any longer, Camiel. Touch me, please.” “Impossible,” he says. “Kiss me.” “I can’t kiss you. […] I cannot touch you, Marina. Not yet. You’ve come too soon.” He is unreadable as he returns to his room, called back by Pascal. Before he leaves, he counsels Marina: “Have faith. And patience.”

The next morning, Richard discovers a mysterious tattoo on his shoulder: a black X. Visibly shaken, he hides it from Marina. Instead, they bicker about the children, about work. Stine has the day off, so they allow Pascal to take the children to school. Marina searches the grounds, presumably for Camiel. In the summer house, she encounters a pale hound. Overwhelmed by a sense of the uncanny, she whispers, “Camiel?” But Camiel appears at the door with the hound’s owner.

Meanwhile, Ludwig and Pascal have taken the children to the seashore. They descend into the ruins of a wartime bunker, offering the children a sleeping draught before opening a kit filled with scalpels. Soon, however, they bring the children home. Pascal, holding Isolde: “They’re a bit tired. Shall I put them in front of the TV? They had a long day.”

It’s the evening of the party. Stine brings Arthur for dinner, introducing him to the family. Richard returns from work, visibly disturbed, his attitude fraying. While Arthur speaks with the nearly comatose children, then Richard (he introduces himself unwittingly as Arthur Stornebrink), Stine goes into the garden to retrieve some flowers. In the summerhouse, she meets Pascal, where it’s strongly implied that they have sex. When she returns, her mood has turned stormy.

Things are tense at the dinner table. At first, Richard refuses to serve alcohol. He tells Marina he’s been fired. Dinner resumes. Richard begins to interrogate Arthur about his father’s work, and the fact that Arthur’s father is Richard’s rival – the man who fired him that very day – becomes apparent. Both parties become heated, even violent, and Ludwig knocks Arthur unconscious to stop the fighting.

That night, Stine goes to the summer house, where Pascal is staying. She expects their earlier sexual engagement to resume, but Pascal rebuffs her. It is as if he finds her expectation alien. “Shall I undress for you?” she asks. “No, I’m going to sleep.” “Shall I come and lie with you?” “No, that’s not necessary.” “Don’t you want to hold me in your arms?” “No, thank you,” he says, polite but visibly confused by her continued presence. He turns off the light, and Stine leaves.

Back in the house, the family finishes the remnants of dinner. Tomorrow is Isolde’s birthday. She wants an aquarium. Richard’s mood remains very dark: “Nothing is celebrated in this house.” He takes Marina into the pantry, voicing his paranoia about work. He removes his shirt to show her the tattoo: “I’m scared, Marina. It appeared suddenly.”

A day or two later, all three children are ill. Marina’s decision to call a doctor results in Stine informing Camiel and his companions. Again, Brenda and Ilonka intervene, executing the family doctor perfunctorily and impersonating his substitute. “The children are overtired,” Brenda says. “From the modern world.” “But all three overtired at the same time. That’s very strange,” Marina replies. “Maybe there’s something else? […] Tensions in the family?” Marina straightens up. “There’s nothing like that in our family.” “Good thing, too,” Brenda says. Nearby, Ludwig and Pascal “operate” on Stine, illustrating both the apparent origin of their marks and also they did to the children in the bunker.

It seems that Marina and Richard are making up. He takes her into the garden shed for a sexual encounter – but this is yet another dream, with Camiel crouched over Marina as she sleeps. The dream turns violent when Richard assaults her with a utility knife, and she awakes, flailing at Richard. He responds in kind, dragging her into the shower before angrily departing. Marina rushes to Camiel, dripping. “He’s got to die, Camiel. Richard must die.” She kisses his hand, as if in supplication. “Please,” she implores. He agrees.

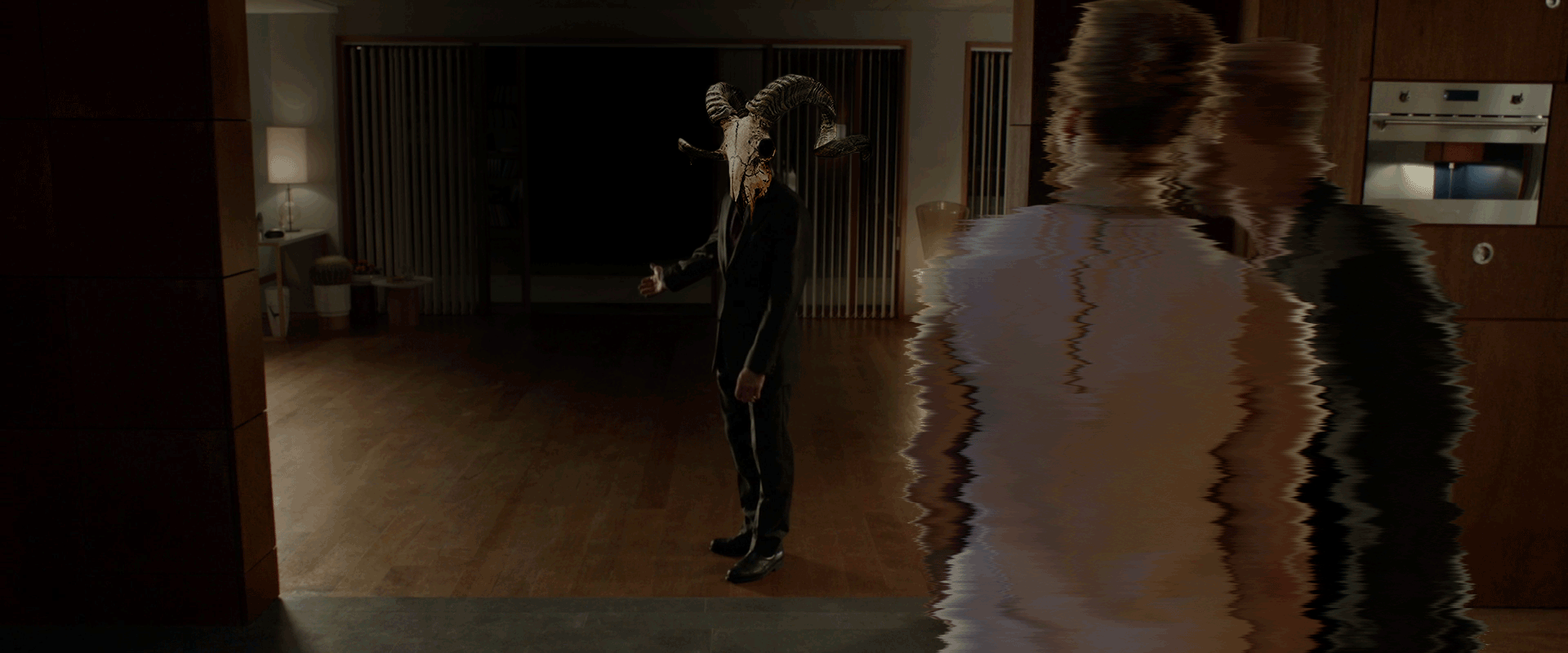

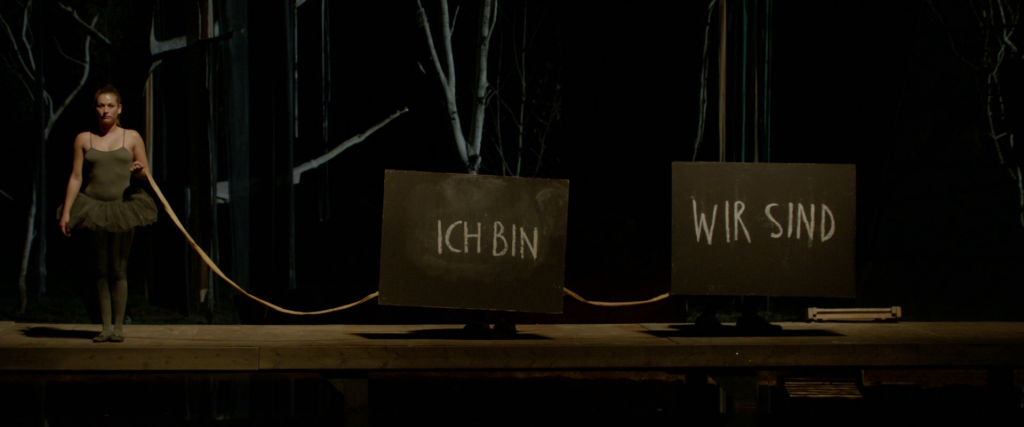

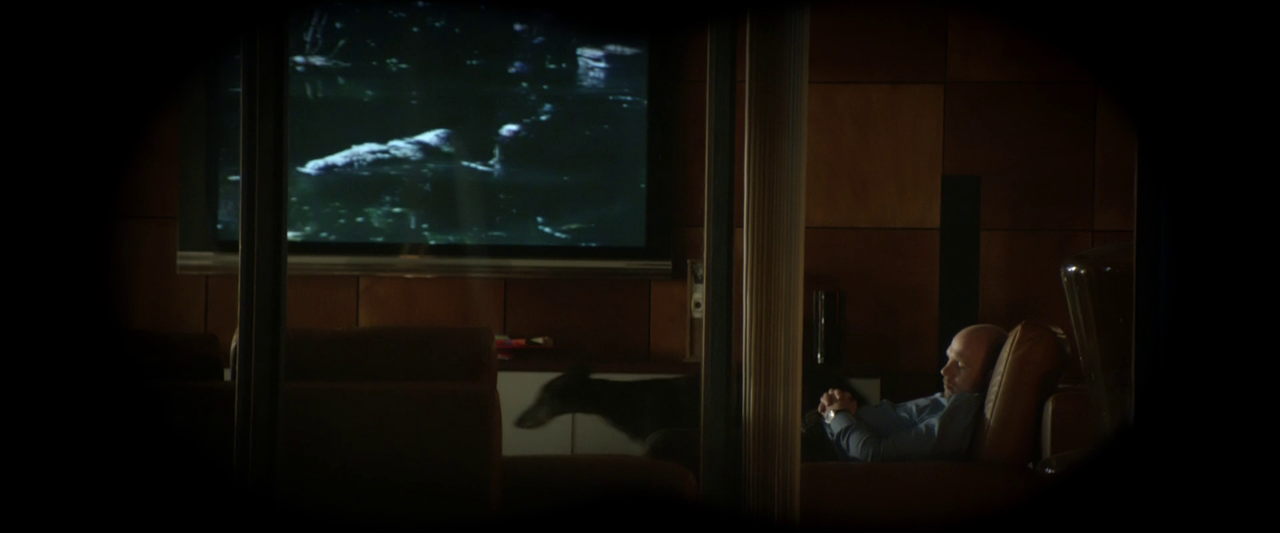

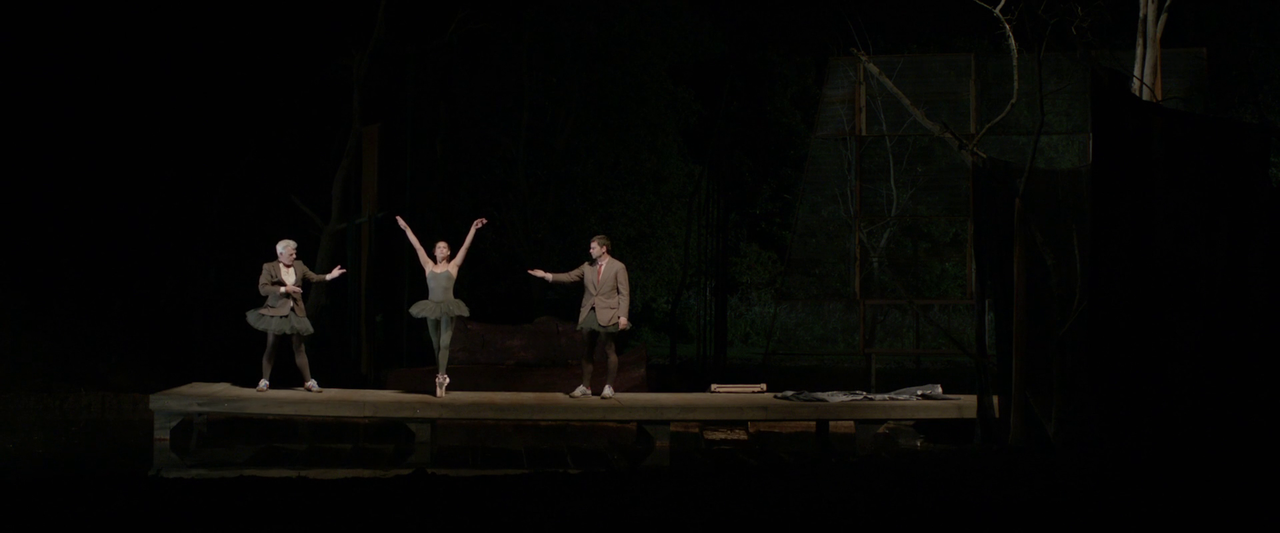

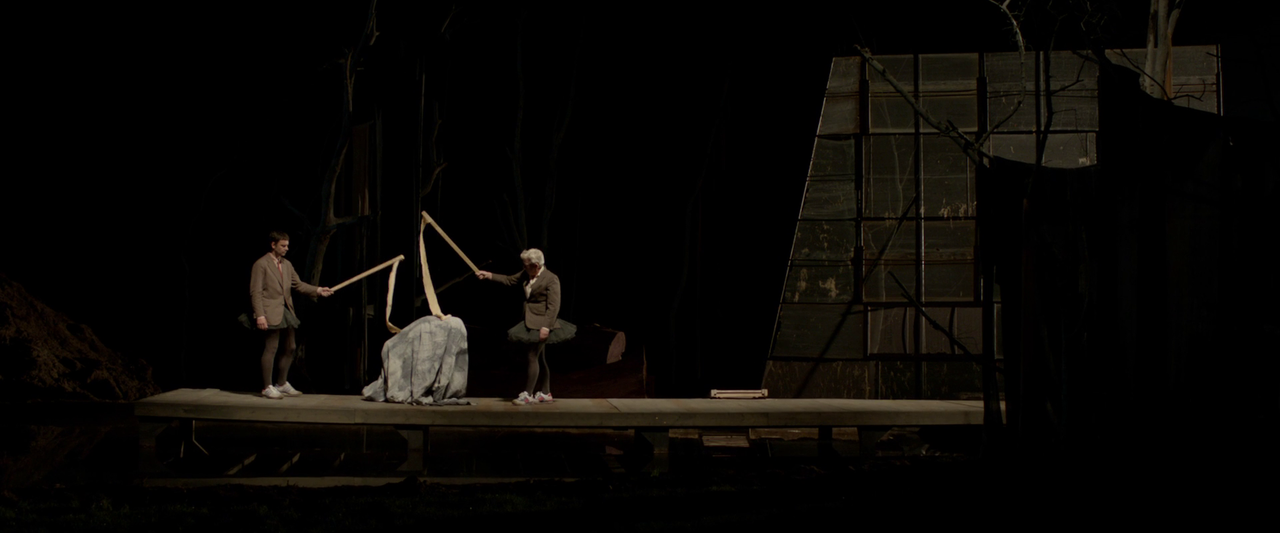

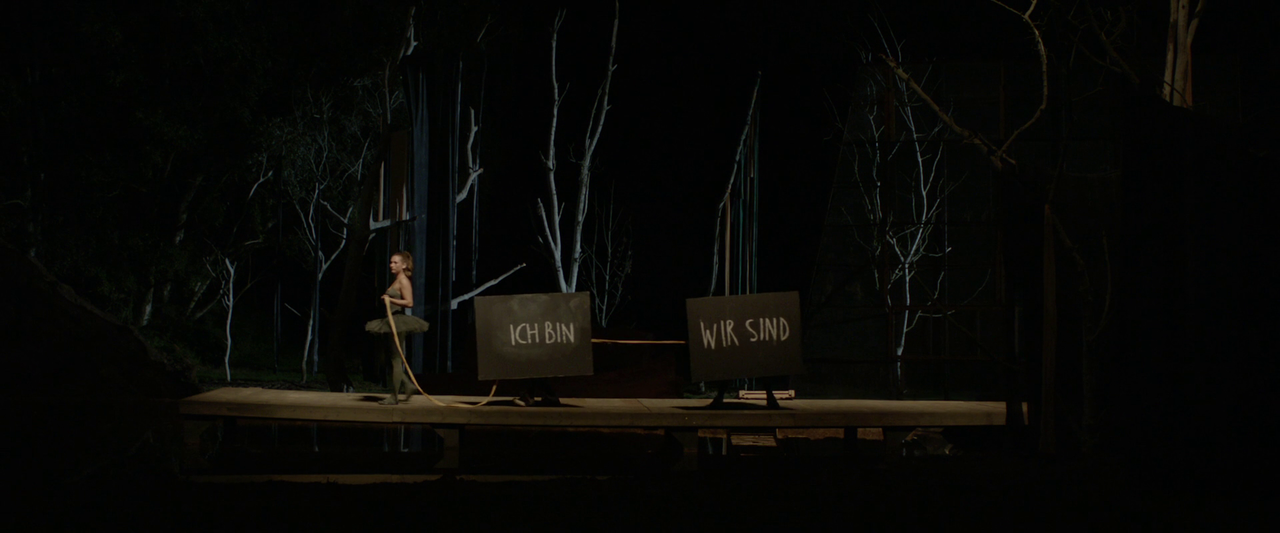

By evening, the children have recovered. Richard returns, and Marina tries to put him at ease, wearing the necklace he’d given her earlier. He got the tattoo removed. Camiel ushers them to the garden, where Ludwig, Pascal, Brenda, and Ilonka stage an enigmatic little playlet on a makeshift platform. It concludes with an assertion of existence: I AM / WE ARE (certainly echoing, perhaps even parodying, the Judeo-Christian God’s enigmatic pronunciation that “I AM,” as well as evoking Sigmund Freud’s “Wo Es war, soll Ich werden”?). During the playlet, Marina’s moods appear to cycle rapidly, almost incoherently: arousal, excitement, grief, guilt, trepidation.

Afterward, Marina serves wine. Camiel poisons Richard’s wine, then Isolde takes it to him. “Isolde,” Marina says. “Give Daddy a little kiss.” Delivering the wine, Isolde bids Richard farewell – although for him, it is only a good night. Camiel and his companions depart for the summer house. As Richard collapses and dies, they watch calmly from there. Marina appears to be in a daze. Everything has been so strange.

After Richard dies, Camiel and his companions enter the house. He introduces them all to Marina properly, and she dumbly greets them, recognizing Brenda as the sham doctor. “Everything will be alright, madam,” Ilonka assures her. Camiel puts on a record, but Marina drags him into the nearby guest bedroom.

“Why all these people?” she asks, still baffled. Nothing makes sense to her anymore. “I want to be with you.” “You are with me, aren’t you?” he says. Her mood shifts around rapidly: confusion, glee, guilt, lust. “I feel so screwed up,” she says. “The garden is finished. You are no longer a gardener.” Desperately, she tries to kiss him, but he fends her off, ushering her back into the main room.

Upstairs, Ludwig is removing the stitches from Isolde’s incision. Camiel and Brenda dance placidly to the music, and Pascal and Ilonka slip into a guest bedroom. Blank, disoriented, Marina goes to the car with a bottle of wine, where she drinks herself to sleep. She awakens in a rainstorm. Upon returning to the house, she finds Camiel, who leads her into her bedroom. After appearing to resolve himself, or perhaps resign himself, he brings her a poisoned glass of wine. They lie down together on the bed, where he finally allows her to kiss his lips. She dies.

In the morning, Pascal and Ilonka throw her body into the freshly excavated pond, following Richard’s. Ludwig fills in the pond with a backhoe as Camiel watches. The grounds are like a scar on the earth, but Ludwig and Pascal are reseeding the raw dirt. Their work concluded, Camiel gathers together all of his companions, as well as Stine and the children, and they depart from the estate back into the forest.

“It’s certainly true that Borgman is dense with allusions to the mythic or otherworldly nature of Camiel and his companions.”

2. IMPERSONAL SPIRITS

Any interpretation of Borgman will turn on how it answers the following two questions: Who are Camiel and his companions, and what purpose do they serve in the film? In summary, they are impersonal agents of disruption. More importantly, they are invited to disrupt the domestic scene, which inexorably enables a mode of exit from it.

Often, it’s suggested that they figure as demons or fallen angels – or, at the very least, as agents of some evil. In reviews, it’s asserted again and again that the film portrays the insidious, slow incursion of evil into a domestic space, culminating in the destruction of that space.

It’s certainly true that Borgman is dense with allusions to the mythic or otherworldly nature of Camiel and his companions.

For example, they emerge from the darkness of the earth and from the depths of the forest (importantly, to whence they return). Traditionally, such spaces – the subterranean or the sylvan – stand in stark contrast to the lawful, well-lit preserves of civilization. Caves play host to devils and dragons, stalked by idols (Francis Bacon), and forests figure as god-haunted and non-Euclidean abominations, twisting labyrinths of the “Forgetful Green.” In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu and Gilgamesh cut down the Cedar Forest in order to achieve independence from divine temper and to yield construction materials for the gates of Nippur. The city must clear a space for itself with axe and fire. In Dante’s Inferno, such a dangerous, lush haunt of the gods becomes an allegorical site of Christian guilt and waywardness: “I found myself in a dark forest, where the straight way was lost.”

Consider also the implication that Camiel and his companions can shift their shapes. The arrival of the two dark hounds – presumably Ludwig and Pascal – figures as an intrusion of the weird into this otherwise largely conventional space. Marina’s confusion and disbelief upon sighting the hounds mirrors our own surprise as viewers. They are impossibilities. Likewise, we see Camiel visually framed repeatedly as a kind of incubus, who perches naked upon Marina as she sleeps.

Additionally, there are the marks – in Borgman, recall, these are vertical scars on the back, resulting from a mysterious incision. Throughout the history of Western witch-hunting, witches were thought to have been marked by the devil as his own. A birthmark, a cut, or a scar (possibly left by the passage of the devil’s tongue) was identified as such a mark, evidence of some diabolical pact, physically placed by the devil after the witch’s cultic initiation. Camiel’s companions do leave such a mark, albeit with distinctly modern care – administering anesthesia, disinfecting the area of incision, and carefully suturing it closed. In Borgman, however, the specific purpose of these incisions remains ambiguous. There is an incision: but is something implanted or removed?

However, all of this remains allusive, mythically vague.

Why, then, the perception of such palpable evil? Probably, it is because of the disruption that Camiel and his companions bring with them, like a storm on the wind. On the one hand, Marina and Richard’s life appears ideal in many ways. At least, it embodies what – under the conditions of late modern capitalism – often valorizes itself as maximally desirable, like a beautiful, elegant home and all the signifiers of affluence and gray plenty. On the other hand, it is as if Camiel and his companions are carefully executing an obscure plan to destroy this ideal, the timing of which is crucial (e.g., Camiel’s text message, his dismissal of his canine visitors, the gnomic cautions he delivers to Marina). They observe impassively; they act inscrutably. Of course, it is inarguable that their appearance eventually results in the total destruction of the domestic scene. There is an element of relativity here. Insofar as we admire and identify with Marina and Richard and their lifestyle – either with its conventional form, or with its luxurious contents – its destruction will appear indeed as the incursion of an evil, as the invasion of dark forces from the wild woods. As such, the failure to extirpate Camiel and his companions from the world (e.g., with which the film begins) results in an existential threat to the very form of life that Marina and Richard embody. This is an irony, perhaps, for the spirits are sleeping until awoken by the din and threat of exorcism: “And they descended upon the earth to strengthen their ranks.”

There’s also the matter of the affective and instrumental opacity of Camiel and his companions.

At no point in the film is there any exposition of their goals or motivations. There are hints of such things, however, especially regarding Camiel, whose distant demeanor occasionally shifts between registers, from the sly (e.g., when testing Richard’s jealousy at their first meeting at the front door) to the pleading (e.g., when begging Marina to let him stay in the summer house while recovering) to the irritated (e.g., when Ludwig and Pascal delay the plan, or when Marina pesters him for an affair) and – perhaps – even to the wistful (e.g., when Pascal and Ilonka dispose of Marina’s corpse). Nevertheless, all of this remains tremendously understated, and it is clear that no one in the film – with the possible exception of the children and, eventually, Stine – ever grasps whatever design Camiel and his companions have come to execute. We could say: Marina never really knows what she’s invited under her roof.

Indeed, this opacity contributes to the otherworldly quality of Camiel and his companions. They have a plan, but the plan is not of this world – this world, meaning specifically, the world into which they intrude and the world that they eventually leave behind. It is as if we are observing the logic of a fairy tale, which inserts itself like a deadly virus into the domestic scene in order to unmake it (again, we hear distantly mythic echoes: the invitation ambiguously received by a “seducing” spirit, the eerie inevitability of the film’s Pied Piper-like resolution).

Furthermore, we should note the degree to which the impersonality of Camiel and his companions deviates from common expectations about such stories. For Camiel and his companions are not Dionysian agents of chaos. They bring neither Bacchanalia nor Saturnalia, which is to say that they arrive neither to initiate an orgy of excess, nor to reveal the secret lawlessness at the heart of the law. These impersonal spirits are not spirits of revelation, much less are they harbingers of an apocalypse. Instead, they are but fey workmen of a project of undoing or unmaking that allows a mode of exit. I say allows, rather than forces, because it is important to notice that Camiel and his companions force nothing. While they do kill (the “consequences” that Marina commissions when she invites Camiel to stay), the primary characters are never forced to do anything at all.

It is the impersonality of Camiel and his companions that captures our attention, but, despite this, we should avoid projecting our desires and expectations upon them in lieu of attending to what they do, or, rather, to what they make possible. For failing to suspend such romantic projection is precisely how Marina dooms herself. She misreads impersonal action as personal seduction; she misidentifies a certain coldness as a warmth. Accordingly, by virtue of her ultimate inability to leave herself behind – that is to say, to abandon the ruin of possessive propertarianism that subtends the landscape of pathological modernity (which is not to say all possible modernities) – she fails to escape the domestic scene altogether.

The fantasy of personal romance, just like the grand modernist romance of personality, is not an exit.

“[…] Borgman materializes and then ruthlessly examines some of the roots and trajectories of the desire for egress or emancipation from the conditions of late modern capitalism.”

3. LOGICS OF DESIRE

In at least three ways, Borgman postulates and works through logics of desire in regard to an exit.

What I mean by this is that Borgman materializes and then ruthlessly examines some of the roots and trajectories of the desire for egress or emancipation from the conditions of late modern capitalism. Abstractly, this latter mode of civilization functions like a tremendously complicated house of mirrors, designed to reflect and reroute every possible desire for escape into some alternate, yet still self-contained, libidinal pathway. Most calls for reform only seek to add more, or better, mirrors, and spectacles of false revolution tend to refract rousing imagery of a few smashed mirrors around the fractal circuit until it all gets lost in visual noise.

Throughout the film, anything resembling a politics is absent. We are fully within the domain of the post-histoire. When Camiel arrives at the door, he is begging for assistance, like a wanderer inveigling favors from a feudal lord. Camiel’s gambit is to provoke Richard into violence, and the provocation is utterly mild compared to the response it receives. It’s a mistake to think that Camiel makes Richard do anything. As we see throughout the remainder of the film, the terrible violence was already there, lurking underneath the surface like a sleeping monster. This point is extremely important. If Borgman is about evil, then Camiel and his companions are not the primary incarnations of it. To paraphrase William S. Burroughs, before Camiel, and before his companions, the evil was there, waiting. Nor is this insight merely a vilification of Richard as patriarch, despite his misogyny and racism. He is an immature and violent person, prone to rage and unaware of his own dysfunctionality, but he is only part of a much deeper problem, a problem the roots of which vermiculate the entirety of the domestic scene.

This is the meaning of Marina’s dreams. Camiel isn’t poisoning them, or filling her head with antipathy for Richard. Rather, he is stimulating to consciousness her preconscious awareness of the reality of her relationship with Richard – and, by proxy, the reality of her world. Of dreaming, Wilfred Bion writes, “We do not know what a dream is: the dream itself is a representation of what happened. What actually happened when you dreamed, we do not know.” Marina’s dreams offer us a key to this enigma, however. In Marina’s dreams, she makes contact with the real. The dreams function as visions of the seething violence that makes possible and sustains what I have been calling the domestic scene. The point here is not that all possible domestic arrangements are necessarily masks of despair, or toxic sites of repressed violence – that is to say, cover stories for an apocalypse that already happened – but that the apparent economic and emotional affluence of our civilization grounds its social epiphenomena in exclusion, expropriation, and murder (recall the Overlook Hotel, the foundations of which are oceans of blood under tremendous repressive pressure). Hence, there are no political pathways in Borgman except exit, because the concept of the political – indeed, the possibility of a politics – has been exorcised in lieu of the purely social. When all that remains are the graven images of social identity, the only remaining action is to try to find an exit. Hence, the impossibility of meaningful speech in the public fora produces the need for a sacred grove, or foris, a fastness located in the Outside.

We find the first logic of desire in regard to an exit in Marina’s commitment to the fantasy of personal romance, which is to say, in her devotion unto death to the grand modernist romance of personality as such. I intend the word romance here to evoke both its colloquial connotation – that is, romantic love, inflected by a courtly tradition that foregrounds the mise en abyme of propriety and transgression – and the more abstract connotation of a mode of existentially heroic melodrama. Marina desires something from Camiel as her conscious awareness that something is terribly wrong in (or with) her world increases. This awareness first stirs when Richard assaults Camiel. As she performs a relatively superficial ethics of care – fundamentally, Marina always treats Camiel like a servant, and we simply can’t identify her actions with anything like a genuine hospitality (internal tensions latent within the concept notwithstanding) – Camiel becomes for her a pleasing specter of alterity. It’s a deeply romanticized version of alterity, however, one that remains fully within the confines of the domestic scene. For example, consider the difference between Marina’s reaction to the two dark hounds, and her wondering solicitation of the pale hound: Is that you, Camiel? Are you magic? For Marina, Camiel is the promise of real alterity that is indefinitely deferred. Hence, her pursuit of Camiel – first, seeking to secure his mere presence on the estate; then, again and again, endeavoring to force an affair – always only ever figures as Marina’s fantasmatic projection of an alternative that nevertheless remains almost entirely safe. In other words, her desire for an exit may be in some way genuine (indeed, it probably is), but she forces this desire to stay inside the house of mirrors, disguised as differential repetition or progressive enactment. Staying inside leads to death, and the conjunction of Camiel’s kiss and Marina’s death serves as the climax of the melodrama – indeed, as in so many romantic melodramas.

The second logic of desire in regard to an exit complements and exceeds Marina’s, and we find this in Stine’s libidinal transformation. This can be sketched quite rapidly, for the film rightly provides little to no internal justification for the character’s decision. Recall that, after her sexual encounter with Pascal, Stine seems smitten.

Her conventional engagements sour – with Marina, her employer, she becomes resentful and, with Arthur, her fiancé, she becomes sharp-tongued. That night, she returns to the summer house, seeking to pursue the illicit affair. Yet Pascal rejects her. His rejection stands out all the more so for its politeness. We get the impression from Pascal not of derision or dismissal – we fucked, we’re done, get out – but of mild confusion: What do you want from me? Stine leaves the summer house, and we easily could expect a range of plausible developments. Perhaps Stine will become angry and resentful, or cold and withdrawn, and this would appear perfectly justifiable. However, unexpectedly (and with no fanfare at all), Stine decides to confederate with Camiel and his companions. Rather than enacting a micropolitics of resentment, she goes to Pascal to inform him about Marina’s intention to call a doctor for the children. Stine’s decision to ally herself with the fey, so to speak, rapidly entails her incorporation into the group (i.e., she submits to an incision, her story here effectively ends). Arguably, her passage parallels that of the children, but, whereas one might claim that the children are ensorcelled, Stine’s actions can only reflect a conscious shift of allegiance, despite what appears to be a very good reason for enmity.

So what, then, does Stine desire? I’m not confident that we can answer this question substantively, but I think we can foreclose several logical possibilities. It may not be clear exactly why Stine opts for Camiel and his companions, but it is certainly clear that she refuses to inhabit or perpetuate the romantic framework that Marina refuses to give up. Stine’s encounter with Pascal deromanticizes her engagement with Arthur, but it also disrupts her relationship with her employer and with the false domesticity that environs her (i.e., she is “part of the family,” she resides there in the estate, but she is also an entirely fungible worker). Accordingly, Stine’s position in relation to the domestic scene is entirely different. Where Marina is a privileged matriarch, Stine figures as a subaltern, both occupationally and even ethnically (she is Danish, and Marina often speaks to her in English because, while Stine obviously speaks Dutch, there is no reason for Marina to learn Danish in order to speak to a mere servant).

The third logic of desire in regard to an exit refers to one of the rare moments when we receive any significant insight into the interiority or the motivations of Camiel and his companions. This occurs during the staging of their enigmatic playlet for Marina and Richard’s family at the very moment of its dissolution. It is important not to overdetermine this performance, but several insights about the playlet can be gleaned from its performance. To start, the playlet consists of four “acts” or moments. The first “act” portrays a twirling gray ballerina (played by Ilonka), spinning at the apparent behest or threat of two male actors (played by Ludwig and Pascal), also wearing gray ballerina costumes under their characteristic suits. The next “act” features the same two male actors using their sticks to prod at a shapeless human figure (possibly dead) hiding underneath a filthy tarp. The third “act” features Brenda alone, wearing a dirndl skirt and executing a dance with a long, flapping ribbon. Is this an ironic or redemptive inversion of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1569 oil painting The Peasant Dance (I say an inversion because the original painting sometimes is considered to be a moralistic judgment against the materialism of peasant life, the peasants engaged in marriage revels whilst ignoring the Virgin on the tree)?

In the fourth and final “act” Ilonka leads Ludwig and Pascal onto the stage, both leashed like dogs (harkening back to one of their earlier appearances). They carry two signs, which read, from left to right: ICH BIN / WIR SIND. These are the first two conjugations of the German irregular verb Sein, meaning “to be”: I AM / WE ARE. As noted above, perhaps this refracts ironically either the Judeo-Christian God’s self-nomination, or else Freud’s apothegm about the ego and the id. Alternatively, we might read the phrases in terms of a sheer assertion of incorrigible ipseity, as if to remind us: We are a coldness your fires can never burn away completely, we will never be exorcised from your worlds, we fey will always haunt you. At the very least, the phrases imply a logic of supersession, in which a collective WE overtakes or surpasses the singular assertion of identity, divine or otherwise.

The point, perhaps, is that logics of desire in regard to an exit cannot themselves provide an exit. The trap is too well-designed. The teeth bite too deeply into one’s writhing flesh. By hook or by crook, the whole shebang is made to capture and reroute desire, just like a house of mirrors plays with reflections. The only way to escape is by means of an affective dispossession – that is to say, by leaving yourself behind, by cultivating a certain frost in the soul. This is the coldness that functions as the necessary precondition of some subsequent heat, a coldness that whisks into the narcotizing confines of the domestic scene like a cutting draft and performs a kind of enigmatic incision. Something is implanted – perhaps: a feeling, a propensity, a truth – or something is removed – perhaps: an affect, an illusion, a story. It’s quite hard to tell.

“[…] nexion: the coming together of a going, or a confluence in departure […]”

4. EXIT, OR THE NEXION

We already have discussed that from which Camiel and his companions offer an exit.

Now, it is time to explore the degree to which the very process of crafting an exit entails or necessitates the deployment of novel forms of association. Exit is not mere flight, as for locusts before the flame, nor does it have to be. Instead, exit foregrounds the reckoning with certain constraints – indeed, the Outside will provide its own constraints in time. Think of exit, therefore, not in terms of mere transit from one locale to another, but, rather, in terms provided by navigation and sailing. The politics of exit is like sailing away from a familiar shore. To sail away requires the construction of a vessel, or a means of egress that simultaneously serves as a form of association until the voyage concludes. A vessel is the coincidence of a form of association, a means of transit, and a mobile architecture.

In other words, I am suggesting that the very stirring of a decision to seek an exit functions as a possible first step toward a novel form of association and even a reoccupation of the political. Further steps in this direction include the divestiture of our inherited libidinal attachments – what I have been calling affective dispossession – and, as I intend to discuss elsewhere, specific operations intended to effect the necessary disentanglements and to forge novel structures of voluntary obligation (these operations being, namely: institutional detournement, ludic experimentation, material repurposing, memetic warfare, reputational economy, resilience practice, and social encryption).

It is certainly not that Borgman gives us the foundation of a new politics in toto, but it does portray the trajectory of an emergency politics – a politics of exit. The band that departs at the film’s end is not yet a political community, but it is a novel form of association insofar as its adhesion appears only on the basis of a detachment or a dispossession. Again, this is not merely an uncoordinated flight into the woods (or, as in many road movies, the alluring “freedom” of the open road). It is a calculated operation, providing the conditions of possibility for the voluntary self-extraction of the subject from the nightmarish dilemma prison of the domestic scene – indeed, from the libidinal house of mirrors altogether.

I propose the term nexion for this novel form of association, grounded in a mode of collective and individual dispossession of the libidinal norms. It’s extremely rare that I coin or use neologisms, but I don’t think we have a term even remotely similar to what I describe here. Assemblage, assembly, band, coven, family, gang, group, pack, and tribe all fail due to connotative excess or counterproductive historical denotations. Consider nexion formally, then: (from the Latin) nex-, meaning “a binding together” or “a coming together” and (from the Ancient Greek) ion (ἰόν), meaning “going” or “going along.” Hence, nexion: the coming together of a going, or a confluence in departure. Some consider it bad form to mix linguistic origins when coining a term, but the ugly hybridity of this term is intentional, for it captures the capacity to associate across received and traditional lines of distinction. Never fetishize the pure.

Borgman, then, performs a politics of exit, and it concludes by prefiguring the process of nexion formation. Camiel’s incursion into the domestic scene always entailed something like an amoral rescue mission – or, at least, the offering up of a certain fey possibility to anyone with eyes to see. Indeed, he only stays on the grounds following Marina’s invitation. It is her desire for an exit, paired with her abject refusal to leave behind the romance (in every sense of the term), which produces the foundering of her own private melodrama. Ironically, the fantasy of personal romance to which she’s so attached serves as the ultimate cover story for the systemic violence that initially stimulates her awareness that something is terribly wrong. Hence, Marina opts out of the nexion forming in the ruins of the domestic scene. Her attachment to an inherited libidinal framework prevents her from exiting the coziness of her brutalist estate and embarking into the cold new world from which Camiel and his companions first emerged.

It’s worth noting, perhaps, that this cold new world isn’t actually new at all. It exists atemporally, Outside the linear trajectory of any particular narrative of decline or progress. Think of it as the old forest that always exists alongside the monstrous edifices of civilization, where the Marinas and the Richards all reside. It exists alongside them, even now – next to the factories chewing up workers, next to the “free market zones,” next to the burning cities and the pyramids of skulls – just as it was there long before them and just as it will be there long after all such architectures have withered away.

Deep in the old forest, you’ll find Camiel and his companions, sleeping underground. To make contact, all you have to do is to bury yourself.

“Do you know the story of the white child who floats above the clouds?”

5. AFTERWORD: CAMIEL'S STORY

These are all the fragments of the story that Camiel tells Marina’s children.

Do you know the story of the white child who floats above the clouds? Shall I tell it sometime? […]

The white child stood at the edge of the lake in the forest. She was very wary. The lake was perhaps not very large, but it was known to be very deep. Maybe as deep as a block of flats is tall. And everybody knew that there was something alive in it. A beast. A large beast with scales and a beak with five hundred small sharp teeth. And that beast guarded the golden key to happiness. The white child cried. Surely she couldn’t dive that deep? […]

When the white child was missed, a search was organized. In the village church, people prayed to Jesus. But, as you know, Jesus is a bloody bore, only interested in himself. That evening, heavily armed divers went down to the bottom of the forest lake. Fifteen minutes later, they came up, trembling with fear. Couldn’t speak a word. What was it? What did you see? the villagers asked. It’s no use, the eldest diver finally stammered. The beast is too big, and the white child has been swallowed anyway. The white child’s mother fell to the ground, weeping. I want my baby back! I want my baby back! You can’t mean that, said the diver. Your child is in the beast’s guts. It’s already half-digested. Now the mother stood up and looked at the villagers. Is no one brave enough to get my baby so that I can give her a decent burial? There was a silence. But not for long, because Antonius – Antonius, the cripple – stepped forward. I will fetch your child, he said. A chilly breeze started blowing, and the mother kissed Antonius’s hands.